It’s been a few years now since I was in school, but I have fond memories of my history classes and learning about the enormity of historical events which had come before us. This prominently included World War II, the fight against the fascism of the Nazis, and the hardships and sacrifices made by ordinary people in that struggle. However never once was there mention of the Spanish Civil War, and I can imagine that if there had been it would have been portrayed as something which happened in Spain, that it didn’t effect us, that it was just one of the many wars which happened elsewhere in the world. It wasn’t until a few years later, when getting involved in present day anti-fascism did I hear about the Spanish Civil War, it’s slogan of “¡No pasarán!”, and its great significance to us all.

The discovery that between 1936 and 1939 over 35,000 men and women from over 50 countries had left their homes in order to volunteer willingly for the Republican forces in Spain, to stand against the Nationalist fascist rebel forces of General Franco, was a momentous one, and initially difficult to comprehend.

In February 1936 a Popular Front Government had been narrowly elected by the people of Spain and began to enact a programme of social and economic reforms. They were planned to modernise the state, improve the income of workers and peasants, to carry out land reform, and massive education measures to tackle the abundance of illiteracy which was widespread at the time. But these involved removing the Church’s monopoly in the school system, as well as a reorganisation of the countries Military, all of which horrified the established elites. The military revolted, and a coup was attempted but did not successfully capture Spain in its entirety, with the People’s Front Government retaining two thirds of the country’s territory, including its capital and the vital industrial regions of the Basque Country and Catalonia, due to the support of its people, the majority of its navy and air force.

But Franco called upon the assistance of Nazi Germany and fascist Italy, and within days the military balance of forces had been transformed, as had the conflict from Civil War to a miniature World War, with the support of Germany’s Air Force, divisions of Italy’s regular army, and Moroccan soldiers from Spain’s African army to assist the Nationalist forces. It was clear that the militia-based Government forces were badly out-gunned and lacked the military experience to repel the oncoming tide, so they turned to the Soviet Union for aid, with the Comintern (Communist International) establishing the International Brigades to help defend the Spanish Republic.

Early volunteers came from countries which had already fallen to fascism, such as Italy, Portugal, Austria and Germany, with scores to settle, before and influx of foreign volunteers flooded the Republic. From Britain & Ireland an estimate of more than 2,500 volunteered, with as many as 80% of them being members of the Communist Party of Great Britain and its Young Communist League. Records from the International Brigades Association indicate that 923 were listed as members of the Communist Party and 169 were listed as members of the Young Communist League. It’s difficult to know for sure, as many travelled under false names, and did not list their political affiliations for fear of being captured and singled out because of them. The average age of volunteers was twenty-nine, although the most common age was twenty-three. Volunteers came from overwhelmingly working class backgrounds, with large numbers hailing from cities such as London, Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow. Only a small number of them were unemployed, with large numbers involved in industrial occupations such as labouring, construction, shipbuilding and mining.

Many of these volunteers had been previously involved in fighting the British Union of Fascists at their meetings and marches, such as in Cable Street in October 1936, realizing that direct action in confronting fascism was a highly effective strategy which also revealed its true nature clearly to the public. One of the volunteers from the Young Communist League, Wally Togwell, who was a waiter from St. Pancras said:

“Wherever the fascists were, our group of the YCL was there also. I was thrown out of the Albert Hall, I took part in anti-Mosley demos at Olympia and Hyde Park, I was at Cable Street helping to erect barricades.”

Joseph Garber, a cabinet-maker’s apprentice from Bethnal Green in London, and also a member of the Young Communist League, said:

“I decided to go to Spain especially after the Cable Street battles when we stopped the Blackshirts getting through.”

George Green, a member of the Communist Party who later died in action, wrote the following to his Mother from Barcelona:

“Mother dear, we’re not militarists, nor adventurers nor professional soldiers. But a few days ago on the hills the other side of the Ebro, I’ve seen a few unemployed lads from the Clyde, and frightened clerks from Willesden stand up (without fortified positions) against an artillery barrage that professional soldiers could not stand up to. And they did it because to hold the line here and now means that we can prevent this battle being fought again on Hampstead Heath or the hills of Derbyshire.”

It is clear that politics was a major factor in those who chose to join the International Brigades, and although not everyone was a member of the Communist Party or Young Communist League, such as Winston Churchill’s nephew Esmond Romilly, it was still a left-leaning understanding of the real threat of fascism which fuelled them in their journey. A journey that soon became harder to take when in February 1937 volunteering for the Brigades was made illegal following the implementation of the Foreign Enlistment Act and the extension of the Non-Intervention Agreement, which both Britain & France had agreed to alongside over 20 European countries in the early days of the war. It was this very act of non-intervention which made the International Brigades so vital, as the Spanish Government was denied the support from those counties, while the Nationalists had the full support of both Hitler in Germany and Mussolini in Italy. This was bolstered even further by American multi-nationals who supplied Franco with large quantities of oil and vehicles. The balance of forces was clearly against Spain, and without the arms embargo of Britain & France, the Spanish Republic likely would have won.

But this did not stop the British people from joining the International Brigades, with many travelling from Victoria Station in London dressed as weekend tourists, travelling to Newhaven before catching a boat to Dieppe, France, then a train to Paris, then to Nimes before getting off at Arles. They would then split into pairs, boarding a coach to Perpignan, before being issued with special shoes and climbing the Pyrenees mountains into Spain. All this complicated subterfuge to avoid detection purely because the Non-Intervention Agreement had made it illegal for them, while both Italy and Germany could openly send men into Spain.

After the journey alone, to dismiss the volunteers as adventurists or as an act of youthful folly, would be incorrect. These were people dedicated to the cause, who had to attend interviews and medical examinations before being accepted. Where military experience was first and foremost, but with political understanding and dedication coming a close second.

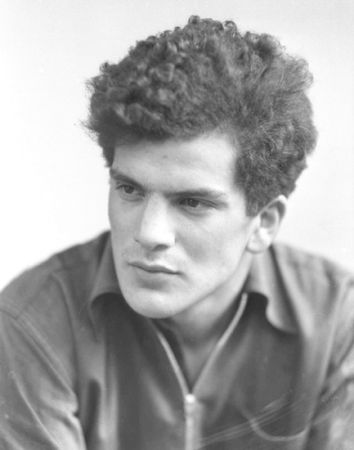

One of the most well known volunteers from the Young Communist League was John Cornford, a young poet and student from Cambridge who happened to be the great-grandson of Charles Darwin, and who was the first Englishman to enlist against Franco. Just prior to his first Christmas at the front, Cornford wrote home to his girlfriend, Margot Heinemann, saying: “No wars are nice and even revolutionary war is ugly enough. But I’m becoming a good soldier, longish endurance and a capacity for living in the present and enjoying all that can be enjoyed. There’s a tough time ahead but I’ve plenty of strength for it.

Well, one day the war will end — I’d give it till June or July and then if I’m alive I’m coming back to you. I think about you often, but there’s nothing I can do but say again, be happy, darling. And I’ll see you again one day.”

Two weeks later, on December 27 1936, Cornford turned 21. The next day he was killed in action near the town of Lopera in the south of Spain.

A lesser known volunteer was Charlie Hutchison, chair of the Young Communist League branch in Fulham and the only Black British volunteer to join the International Brigades. He was barely 18 when he became one of the first volunteers, giving his reason for going as:”I am half black, I grew up in the National Children’s Home and Orphanage. Fascism meant hunger and war.”

He served two years until the end of the war, and after suffering injuries he refused to be repatriated because of this young age, so instead was reassigned as an ambulance driver for the Republican Army. Charlie did not die in Spain, in fact he went on to join WWII in the British Army, serving in North Africa, Iran, Italy, France & Germany. In April 1945, he was among those who liberated Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp. He died in 1993, after living a long life, and remained a Communist throughout.

British volunteers continued to be involved in many of the major battles, right up until the last desperate Republican assault across the River Ebro in July 1938. Their casualties in Spain were high, with as many as 626 killed, many others suffering life-changing injuries, and a fair few ending up in fascist prison camps until just after the war. The last of the brigaders were withdrawn at the end of 1938 and returned to Britain in December after a farewell parade in Barcelona. In the presence of many thousands of tearful, but cheering, Spaniards, Dolores Ibárruri (deputy of the Spanish Communist Party) addressed them:

“Comrades of the International Brigades! Political reasons, reasons of state, the good of that same cause for which you offered your blood with limitless generosity, send some of you back to your countries and some to forced exile. You can go with pride. You are history. You are legend. You are the heroic example of the solidarity and the universality of democracy… We will not forget you; and, when the olive tree of peace puts forth its leaves, entwined with the laurels of the Spanish Republic’s victory, come back! Come back to us and here you will find a homeland.”

Upon their return to Britain they were greeted with massive celebrations and an emotional welcome at Victoria Station in London, before returning back to their families and friends, and to their somewhat normal working lives for a brief period of time until the outbreak of WWII. Indeed, following the death of Franco in 1975, a new democratic government replaced the old regime, and as a gesture of gratitude to the international volunteers who had come to Spain, sixty years after the outbreak of the war, the Spanish Government offered citizenship to the surviving members of the Brigades.

Although the Republic fell and victory did not come to Spain, it influenced the knowledge and opinion of the British public, created thousands of new activists, drawing them into the anti-fascist struggle, and contributed massively to the long term defeat of fascism later on in 1945.

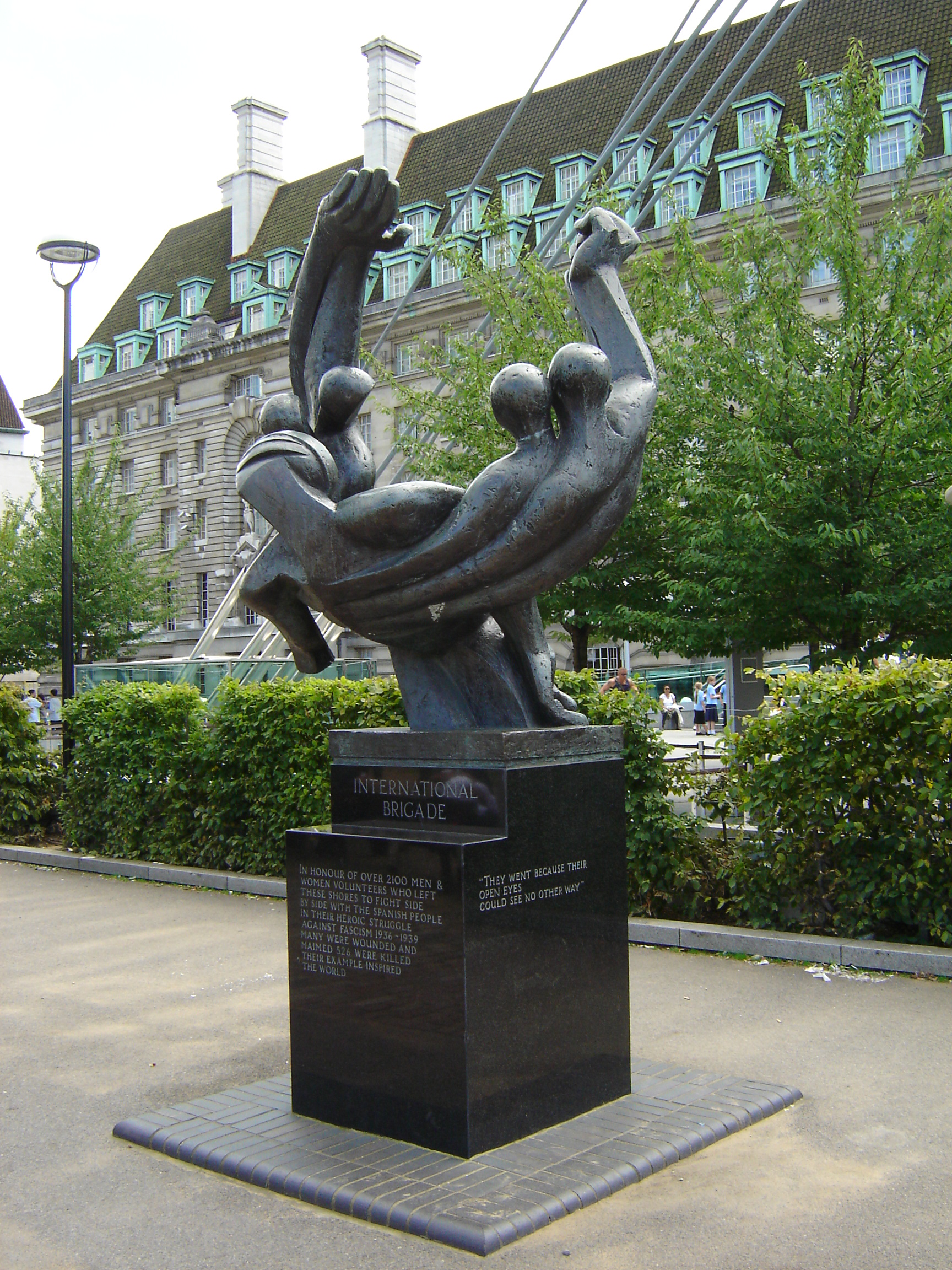

Around the world today you can find monuments and memorials dedicated to the memory of the volunteers who gave their lives for liberty in the face of fascism. There are hundreds of them in Britain alone (www.international-brigades.org.uk/memorials), the most prominent being on the South Bank of London across from Westminster.

The majority of battlefield monuments erected in Spain during the war were completely destroyed by fascist forces, and many of them around the world today continue to be graffitied upon and damaged. But there is one not so prominent which was found laying in the undergrowth of the remote mountainside of the Sierra Pandols in Catalonia, discovered in spring 2000 having been undisturbed for more than 60 years. It was a makeshift pyramid of three cement blocks laying on top of one another, hurriedly built by Percy Ludwick, a British military engineer, during the intense heat and brutal fighting of August 1938.

It has the names of thirty Britons, Canadians and Americans from the 15th International Brigade crudely inscribed upon it, all of whom gave their lives fighting in battles along the Ebro. Among the names are that of Labour Party councillor and Olympic Gold Medallist Lewis Clive, and Young Communist League & Communist Party members David Guest, Harry Dobson, Morris Miller, and Wally Tapsell who, like all those from Britain who died in the Spanish Civil War, have no known graves. But their names are preserved not only on that memorial, but today in the hearts of Communists throughout Britain and around the world.

It is said that we die twice in this world. Firstly, when our physical body perishes, and secondly when our name is uttered for the final time. It is our duty to ensure that those who fell in Spain, who gave their lives for Liberty and Humanity against fascism, to make sure that their names and their deeds are never forgotten. That we do not let them die that second time.

Even after studying and learning about the journey and motivations of so many young communists who volunteered, it is difficult to know whether in similar circumstances against a similar enemy, if I would do the same thing, make the same dedication, and potentially the same sacrifice. I like to think I and many others would, as a few in recent years have done so when joining the Kurdish struggle of the International Freedom Battalion in Syria. But until the call for aid is made, it’s impossible to know for sure.

As the Young Communist League of Britain celebrates its one-hundred-year anniversary this year, we will reflect on the struggles waged by those who came before us, learning about their sacrifices and victories, and holding firmly on to our past as we stride forward into our future. Whatever that may hold in store for us.

“They in our hearts will never die

who carried freedom’s banner high

And fighting died and gave their all

To break the strangling fascist thrall

Tell them in England if they ask

What brought us to these wars

It was not fraud or foolishness

Glory, revenge, or pay

We came because our open eyes

Could see no other way.”

Joe Weaver, is Secretary of the YCL’s East of England Branch

Further Reading:

To Make The People Smile Again – George Wheeler

Understand The Weapon, Understand The Wound – John Cornford

John Cornford: A Memoir – Pat Sloan

Unlikely Warriors – Richard Baxell

The British Battalion of the International Brigades in the Spanish Civil War 1936-1939 – Richard Baxell

Miners Against Fascism – Hywel Francis

A Centenary for Socialism: Britain’s Communist Party 1920-2020

Useful Websites:

International Brigades Memorial Trust

Marx Memorial Library (Their Spanish Collection is the largest archive and library on the British response to the Spanish Civil War in the UK)

‘Voices from a Mountain’ by David Leach (A Spanish Civil War documentary)