Territorial army training is one thing and real war’s another, but it didn’t take me long to make up my mind to get away to Spain and to do what I could to help against Fascism.

I arrived at Barcelona on September 19, in the days when Franco was promising all sorts of things about the fall of Madrid, and when Germany and Italian Fascist armies were beginning to invade the country.

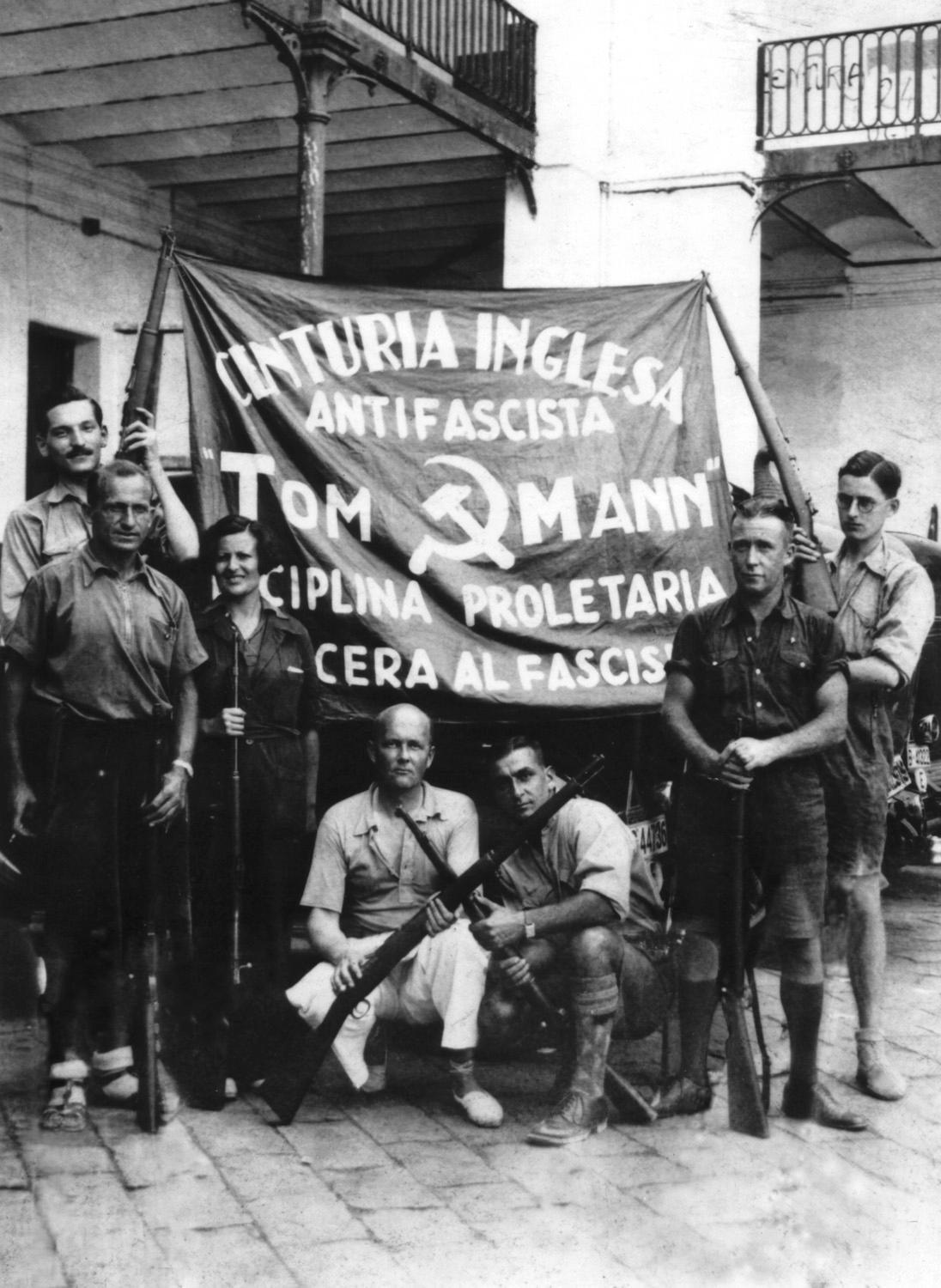

There were seven of us British lads together, and for a whole month we hung about, doing some sporadic training using sticks instead of rifles, and it was just exasperating having to wait because there were not enough arms for us—or for the hundreds of young Spaniards who also wanted to be off to fight. At the end of October we went to Albacete, joined the newly formed International Column and after five days pushed off to a little village with a big name where we were to train in earnest for the fighting.

That was the theory, anyway. But the same morning that we arrived, news came through of the big Fascist push against Madrid, and without even unpacking we hurriedly moved on to keep the Fascists out. Those were days of some excitement. All sorts of wild rumours were flying around, and it speaks heaps for the spirit of our boys that the only ones we paid the slightest attention to were those which said that Burgos (the Fascist headquarters) had fallen. After jolting along for some miles in an open lorry, we arrived in the evening at a little village where we stayed for two days.

Then at half-past one we were awakened, given coffee (wonderful stuff in the early morning) crowded on lorries and half-an-hour later we rumbled off to the S.W. sector about 14 kilometers from Madrid. We arrived at 7 a.m and went straight into action.

We were on the extreme right of a curved line of attack. On our left were anti-Fascist boys from Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland and other countries. On their left were the Spanish boys. Our job was to attack a castle with walls about 15 feet thick on the top of a hill in which the Fascists had fortified themselves. They had about 150 machine guns which kept up a relentless fire, while their artillery sent over loads of shrapnel.

The first 10 minutes of the attack were the worst. In spite of my “terrier” training, I was just plain scared—and I’m not ashamed to admit it. You can picture the thing for yourself. In front of us there were hundreds of yards of ploughed field. Rising from it was a hill and on top the castle. The gun fire didn’t worry me or the other boys a bit. But as I went forward, I became aware of a zipping whistling noise in the air, and as we got closer, the zip zip got louder, and then suddenly I knew that the air was just thick with machine-gun bullets.

Did I duck? You bet I did. The funny thing was that I didn’t feel afraid, but when I tried to get up off the ground, my legs wouldn’t move for about three minutes. The same thing happened to the other lads, but we soon got over it, and then we began to advance—rush 20 yards, down—rush 20 yards, down, until we got as near as we could, about 200 yards from the foot of the little hill.

Each time we dropped for firing, we had to pile up some of the loose earth as a protection; that gives you some idea of the exposed position we were in. Davie Marshall was wounded, not seriously, and he was got out of the way. We lay about 200 yards from the castle, the air around thick with machine-gun bullets and shrapnel, waiting for our guns to back us up; but there was no reply to the fascists’ heavy fire, and we found afterwards that there was insufficient ammunition. Nevertheless we hung on grimly, firing our rifles and machine guns whenever we saw a chance of scoring a hit; you can imagine what it felt like to be shooting bullets at walls about 15 feet thick, while the enemy had everything in the way of weapons to his advantage.

Suddenly we heard a faint droning that grew louder and out of the sky the German bombers came. We watched as they circled above us and released two tiny objects which came zip-zipping down to blow two terrific holes in the ground and almost to stun us with the deafening rocking explosion. It’s a horrible feeling. I can tell you, lying in an open field, watching bombers circle almost lazily overhead, each one seeming to be singling you out as they drop their high explosive bombs. It’s a miracle that not more than one was killed and only half a dozen wounded. It was a Polish boy that got it, he was killed instantly.

If cursing could have brought down airplanes, those fascist bombers wouldn’t have lasted five minutes; but neither cursing nor fire from our machine guns was any good, we just had to grit our teeth and hope that some of our planes could be released to deal with the Germans. None came over, however, so after a while we withdrew. We didn’t have any ground, because the fascists couldn’t leave their castle to advance; but neither could we get them out because of the lack of fighting weapons of any size, the silence of airplane reinforcements, and of a unified command. The whole engagement took from 1 a.m. until 3 a.m. the following morning.

After we got back to our original positions, we had time for a breather, because the front we were on was comparatively quiet. I got a chance now and again to use my mine thrower, and each time I scored a hit the boys cheered like mad. We also got a chance to get to know each other—we represented many nations and spoke many tongues, but we all felt the same way towards the enemy and we all had the same ideals; so we got on pretty well. One of the most thrilling things was the way all of us could sing the same Socialist songs even though the words were in different languages, and I tell you it gave me a real deep feeling of comradeship to hear the German, French, Italian, British, Polish and the six odd other nationalities all join in the same songs with the same deep feeling and meaning. For music we had a mouthorgan—played sometimes by myself, sometimes by a fair haired German lad who had escaped from a concentration camp.

After a few days of this we were transferred to the Casa del Campo (West Park) on the outskirts of Madrid, where the fighting was hottest. It was there, you remember, that the fascists nearly broke through. On our way, we met many people—women and old men—who with tears in their eyes cheered us on—“Non Pasaran, comrados“ they said, and they meant it. I reckon that these women would have taken up table knives against Franco had he got inside Madrid.

Anyway we soon found that what they said about the Casa was true—it was a tough spot. Out trenches were not much good, they were not deep enough nor had they sufficient in the way of communication lines. The Polish boys soon put that right, however. They dug a 500-yard trench with communications and dug-outs and piled them high with sandbags. Soon we were practically impregnable, thanks to their work. These Polish chaps, by the way, were some of the best fighters we had. They never lost their heads once, and on the single occasion we had to retreat, they did some heroic work bringing back every single machine gun and piece of ammunition. Ammunition was particularly valuable; it was so scarce.

During the whole time we were defending the city, I never saw more than a handful of Spanish rebels—only Moors and Foreign Legionaries. The Moors were mostly young, some under 17, obvious hill boys who didn’t know what the war was about but had been forced into the business. The Legionaries were everything that’s been said about them—real tykes. You could tell by their faces (and we saw plenty of dead Legionaries) that type of inhuman creatures they were. The Moors were good fighters, but I reckon a square meal would have killed some of them, they were so emaciated. It was pitiful to see them with their legs as thin as reeds, and sunken cheeks drawn back in the last horrible grin of death.

Not enough has been said in my opinion of these unfortunate natives whose deaths have been caused by Fascism as much as the deaths of the sons of Spain.

At University City we attacked a big building called the White House and captured it. As night we withdrew because no reserves came up, but the next day we took it again. We repeated this altogether three times, withdrawing at night because of lack of reinforcements. The third time we held on and after two days reserves came up and we went back to rest. We had heard this time of a lot of British boys who were with another section of the Column, and we asked to go and join them. But the German lads wouldn’t part with us for anything, so we stuck with them and only once were we together with our countrymen, and that was in a battle we all took part in together.

After our rest, back to University City. The Fascists had recaptured the White House, but we put them in a tough spot. Their food had to be brought up in tanks of which Franco appeared to have an unlimited supply. Fighting was sporadic and we took advantage of the situation to dig ourselves in even better than we had already. We arranged our machine gun nests at night, and the German boys were really hot at this. One of them fixed himself up with a green umbrella which he covered with leaves, and you couldn’t spot him as he squatted in a shell hole, machine gun between his knees, cigarette in his lips, hidden by the camouflaged umbrella from beneath which he poured a deadly hail of bullets upon any fascists who showed themselves.

Carl Adler, member of the German Young Communist League, was killed at about this time with a dum-dum bullet which tore a great hole in his chest as big as a saucer. Hans Beimler, one-time Communist member of the German Parliament, and who had escaped from a concentration camp, made the funeral oration. He said Carl was the second of five who had escaped with him and come to fight on Spanish soil against their enemies. Since then Hans himself has gone, so has a fourth—a lad named Willie something, one of the finest looking and best built chaps I have ever seen. What’s happened to the fifth I don’t know, but this I do know, none of them begrudged their deaths; they knew they were fighting for mankind, and they fought bravely not for the sake of killing but for the sake of stopping killing for ever.

The good work we had put in, together with that of the other sections, had checkmated the fascists who could get no further. Since November, they have never once advanced, whereas the Government have gradually been able to attack, and now to drive the enemy back from the gates. Of course the single united command they’ve got recently had helped enormously; previously there were dozens of people working out tactics which often were at cross purposes. The Communist Party all along had demanded unified command, and now it’s been done.

There’s one thing I’ll never forget. The Fascist bombers used to come over every day but they didn’t drop their bombs on us; they flew on to the city to kill women and children. It was exasperating during the early days, before we got enough fighting planes, to watch them—great heavy winged messengers of death. One day Lorimer Birch (he’s killed now) sat watching them come up, and suddenly he could stand it no longer—he jumped up, shaking his fist at them and shouted, “Bomb us, you bastards, bomb us,” but of course they merely flew on, and later we could hear the shrieks and moans of the dying kiddies. It was terrible.

After a bit, we went back for another rest, this time in a castle behind Madrid. On December 14 (I remember it because it was my birthday) I heard the drone of a plane. I went up to the top room and from the skylight saw a fascist bomber-fighter circling round overhead. He must have been suspicious of the building, because he circled round dozens of times, and then began to spray bursts of machine gun bullets. Suddenly I heard a high-pitched booming noise that seemed to tear itself out of the sky, and before the bomber could make off, a tiny fighter plane seemed to streak with incredible speed out of nowhere. The fascist turned tail, but he didn’t stand a chance. The Government plane played with him like a cat with a mouse. He circled round him, performed all kinds of stunts, forced the fascist to go where he wanted him to go, and then, when he got to a nice level stretch of ground, forced him down and finished him off without wrecking the plane too much. Those were the days when these tiny streaky planes that are all engine and machine-gun and fly faster than anything anyone’s ever seen before were new to us; but they’ve been the means of saving countless numbers of lives.

The last battle I was in took place shortly after this at a village about 17 kilometers West of Madrid. We were to the left and a little way behind the village, Frenchmen and Spaniards were in front of it, some more English boys were to the right. We knew the fascists were getting ready for a big push; because of the ceaseless bombardment. Some of the shells didn’t explode, however, and in several we found “Salud camarades, U.G.T.” written on a scrap of paper. The reason for this is that they are made in Burgos and Seville by Spanish workers under armed guard; but it’s an inkling of what will happen when the Government gets to the outskirts of these towns.

Anyway, the artillery fire became hotter and hotter, so some of the German boys went out one night to bring back the fascist outpost in order to find out what was afoot. These German lads were devils—they didn’t care a hang; if they thought a job needed to be done, they did it. They soon returned bringing with them a couple of Moors—who told us that a tremendous force of German Nazis had come up and were preparing to attack.

The attack soon came, and the Nazis approached the village in the well-known German formation. With the other British boys, we went forward, dug ourselves in as quickly as we could, and covered the retreat for the rest.

It was here that I got mine. I had to get from one trench to another as quickly as possible in order to co-ordinate our work, and chose to risk running across the top. I got it in the neck—literally. The bullet went between my spinal cord and the wind-pipe, and tore the nerves. I felt my arms stiffen and then my legs, blood was gushing out and before I lost consciousness I though it was my finish. They got me away, however, to the hospital where I found myself wrapped like a corpse in a wide cotton sheeting. As I lay there, a doctor came round. To those who were not badly wounded, he gave a card with a number. Those who were as good as corpses he stamped with a number on the head. Imagine what I felt like when he rubber-stamped me! Anyway, they did a few things, and I’m practically recovered—miraculously, so they say.

Since I’ve come home, the Government has gone from victory to victory. From what I saw of the Spanish people, they’re absolutely determined to win, and the spirit of unity is amazing. If it were not for the Nazis and the Italians, Franco wouldn’t stand a dog’s chance.

That’s my story. I’m glad I went; if I were well enough, I’d go back. This is a war which we’re all involved, whether we like it or not. What happens in Spain will determine what happens elsewhere during the next few years. A victory for Germany and Italy will mean war for all of us instead of a few. Defeat for them will mean victory for democracy and for peace.

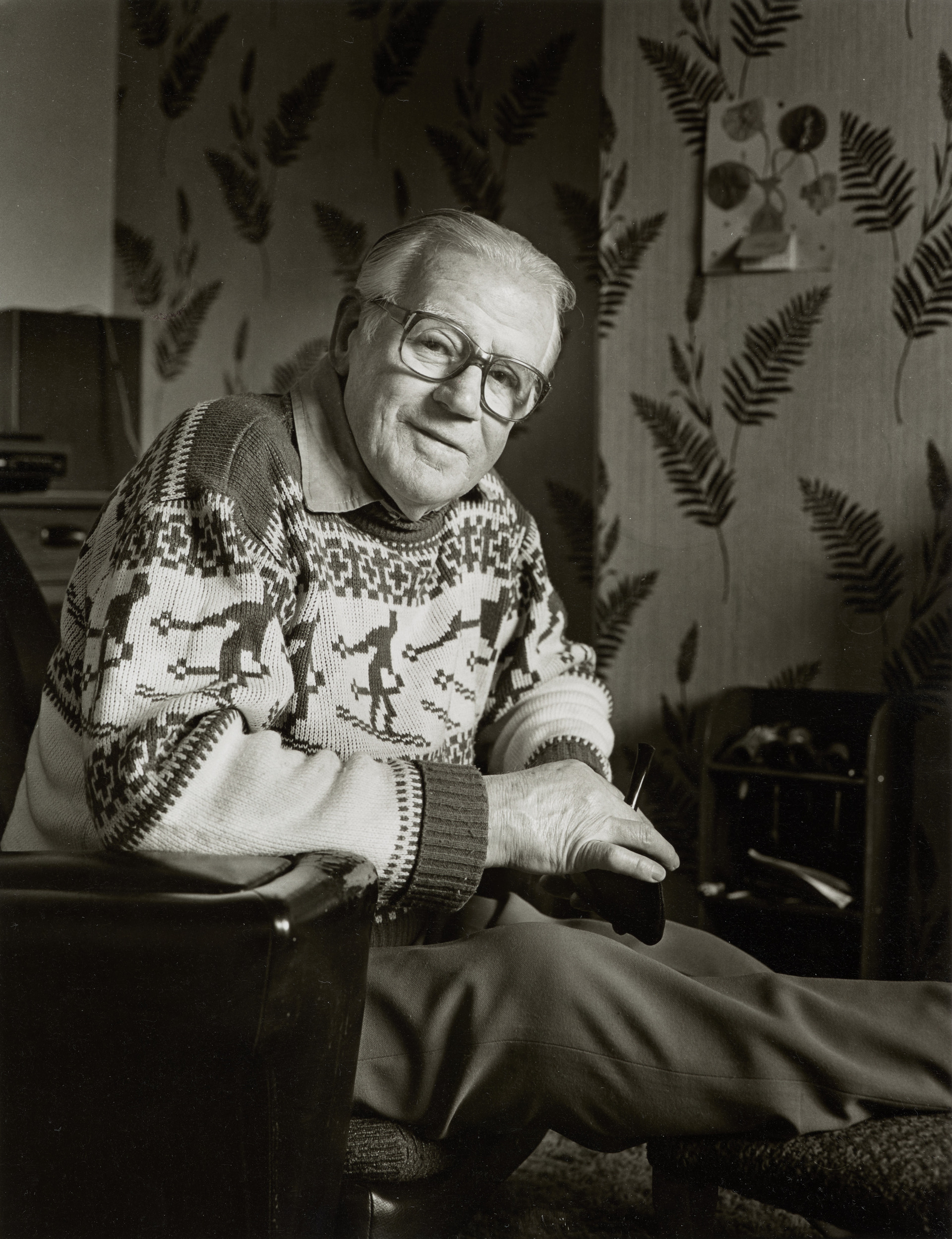

Phil Gillan 1912-1993

We honour their lives. We salute their memory.