The national interests of Iran and the Taliban require them to have considerable relations, but the Taliban have likely come in power through an agreement, believes the Iranian foreign policy analyst Fereydoun Majlessi

Fereydoun Majlessi is a former diplomat, who served in Washington DC and in Brussels in the European community before the Iranian Revolution in 1979. At present he is a freelance journalist, columnist and a foreign policy expert.

Vladimir Mitev: Mr. Majlessi, the new Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi welcomed the Taliban in Afghanistan at the expense of the US withdrawal. In what ways is Iran satisfied with what is going on in its Eastern neighbour and what makes Tehran concerned?

Fereydoun Majlessi: I am not sure if he welcomed the Taliban’s takeover, or just accepted the reality of the event. Iran is a neighbouring country of Afghanistan and hosts millions of Afghan refugees. Furthermore, Iran is an important supplier of goods and materials, and a vital transit road and connection of the landlocked country to international waters. So, regardless of the ruling system there, the national interests of both countries require them to continue their relations.

But if Raisi sees the withdrawal of the Americans from Afghanistan as a reason for anti-American animosity that could be a factor for closer relations, then that doesn’t seem compatible with wisdom and reality. Afghanistan, ruled by the Taliban or anyone else, will follow its own national interests so its rulers will always prefer relations with the most important country in the world!

V. M.: What is Iran’s strategic interest in Afghanistan? In what ways are the Taliban in 2021 different from those Taliban who killed Iranian diplomats before 2001? And what is Iran’s interest in engagement and cooperation with the Taliban now?

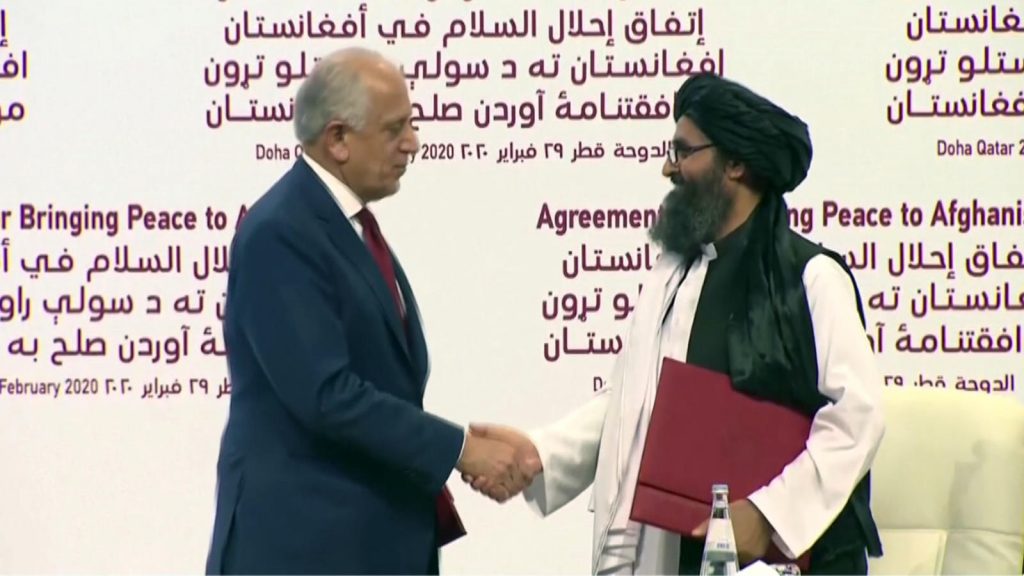

F. M.: As I mentioned, the national interests of both countries require them to have considerable relations with each other. But there are other facts that show the re-emergence of the new generation of Taliban is a complicated phenomenon. Since the opening days of their office in Doha, Qatar and because of the very mild reaction of the Afghanistan government to this clear interference in their internal affairs, it could have been foreseen that a special arrangement was being made. The easy “domino effect” invasion of the cities by a bunch of primitive rural Pashto guerrillas on one hand and the defenceless surrendering and disappearing of the very well equipped and well-trained Afghanistan army units on the other, shows that they’ve been ordered to do so, and it seems to be a part of the deal.

But what kind of a deal could it be? It has been discussed that Afghanistan holds three large deposits of important minerals alongside considerable gold mines. These are lithium, copper and iron ores, which are highly sought after by the USA, China, Europe, Russia and others. Their extraction and production require stability, security, investment and of course machinery and technology to be provided in Afghanistan, under secure conditions. I believe that the long negotiations with the Taliban aimed to convince them that more power and success depend on having more money and wealth and more money could be secured by joining efforts with other factions inside and outside the country. Now the Taliban have declared amnesty for all factions. A political commission has been formed for the peaceful transfer of power by ex-politicians like Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah, and Gulbedin Hekmatyar. So, it is possible that they also will have a slice of the cake if the scenario plays out this way.

V.M.: There are reports that in Panjshir, among other places, anti-Taliban fighters and peaceful protesters are gathering. As that was happening, you wrote a series of articles in Persian, where you discuss the idea of Afghanistan’s division into Tajik-Shia-dominated north and pro-Taliban south. How serious are the prospects of a civil war in Afghanistan? What solutions could be found so that there is lasting peace and security in Afghanistan?

F.M.: I don’t see any chance for the nostalgic and romantic reaction of the Panjshir affair. They need the money and support which the now deceased Ahmad Shah Massoud provided (prominent anti-Soviet guerrilla fighter – E.N). Support similar to that is not available now. But I still believe that the apartheid-like system of domination over the Persian speaking majority of the Tajiks, Hazaras, Heraties, and even the Uzbeks of Mezar can’t last for long time. Reconciliation must follow and peace must be kept, the cultural and national rights of the majority should be guaranteed.

V.M.: The designated foreign minister Amir-Abollahian is widely considered to be a supporter of Iran’s orientation towards east (Russia and China) and the region (axis of resistance) as opposed to Javad Zarif’s orientation towards engaging the West. What should we expect from the Iranian foreign policy under Raisi? How is this expected reorientation being explained? And how will it affect the future of the nuclear deal talks in Vienna?

F.M.: The new minister of foreign affairs is not the designer of the foreign policy. He will be carrying it out as ordered by the supreme leadership, as his predecessor was doing. I don’t see any chance for resuming the talks in Vienna before acceptance of the leadership by the president with mutually agreed dealings.

V.M.: Recently the Tehran Times wrote that all the political obstacles to Iran’s membership in The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation are eliminated and the membership will soon become a fact. In what ways Irani’s national interests coincide with membership in this organisation? And how will this membership influence the Iranian relations with the countries of the West?

F.M.: I don’t know whether an agreement for a membership in that organisation has been reached. It needs acceptance from all member states and issues might arise there, because in such cases the member states don’t like partnering with countries – the actions of which might cause them problems. Indeed, for some member countries of SCO Iran might seem somehow problematic. Besides, even if the membership is accepted, real trade and banking transactions require the acceptance of the FITF protocols by Iran’s government (which aim to counter money laundering and terrorist funding) and also releasing Iran from the ongoing sanctions.

V.M.: The developments in Afghanistan represent not only a security, but also a humanitarian issue as hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees have left or will leave the country. Iran hosts a few million Afghan refugees and economic migrants. What role will Iran play in the humanitarian crisis that unfolds in the region?

F.M.: I hope the problem will be resolved soon, once the panic is over. But if it persists, it would be highly advisable that Iran brings up the case to the international scene by requesting help from UN to establish refugee camps in the border regions with Afghanistan.

V.M.: To what extent the avalanche of recent crises in Iran – water shortage, COVID-19 crisis, international sanctions, inflation, unemployment, social protests, etc. can be resolved without significant improvement in Iran’s relations with the world and international cooperation? How likely it is that the Afghan crisis creates conditions for significant improvement of the Iran’s relations with various foreign powers of the West and the East, which might look for Iranian contribution to the resolution of regional crises.

F.M.: These are important problems that the government must handle and solve. Regardless, Iran is a great country and has the potential to overcome these sorts of problems by obtaining correct decisions and coming to better terms with the international community.

Vladimir Mitev, is a journalist for Barricade (Барикада) and is currently pursuing a doctorate in Iranian literature at Sofia University. He also runs a blog on Iran.

This article was originally published on Barricade