I remember being at a workshop event for trade union branches in my city last year. For an ice breaker, we were told to go around and tell the group which moment in history we would have liked to have witnessed. One woman proudly proclaimed: “I would have loved to have seen the fall of the Berlin Wall”. My turn came up, and it took every fibre of my being not to say: “I would have liked to have seen the Berlin Wall going up.”

The German Democratic Republic, better known as East Germany, is one of the favourite punching bags of every political stripe, from conservatives to liberals to Western leftists. The GDR is remembered as a ‘totalitarian’ nightmare with bleak barriers cleaving a city in two, towers bristling with barbed wire and snipers, and Stasi informants lurking in every apartment block. Life for the average GDR citizen in the Western psyche is portrayed as a depressing, all-consuming misery.

I’d like to use this article to give a counterbalance to this popular conception of the GDR, with a focus on the infamous Wall. For brevity, I’m going to assume some familiarity with the common criticisms of the East German state. After all, if there’s one thing the media isn’t short of, it’s criticisms of communism. Some people think the rational response to vitriolic anti-communist propaganda is to provide a sober, balanced, and objective analysis, such as the fantastic book Stasi State or Socialist Paradise. Instead I’ll be focussing on the lesser-known context of the country, what it was up against and exploring why it took the path it did.

Following the Second World War, it’s safe to say that Germany was in a sorry state. The collective delusion of the Nazis had led the country into ruin, killed tens of millions of people and completely reshaped the global order. However, this destruction was far from uniformly distributed. While the Nazis sent their best troops and armour to the eastern front to fight the Soviets in the most intense fighting, the western front was seen as an unfortunate inconvenience in comparison. Unlike the western front, the Wehrmacht enacted a scorched-earth policy through their several thousand-mile retreat, on top of the systematic extermination that was conducted behind German lines. This difference is well illustrated by the statistics: roughly 80% of all German casualties during the war were sustained on the eastern front.

By the war’s end, the eastern half of Germany was practically obliterated, especially compared to the western half of the country, where scorched-earth tactics were not employed to the same extent. To complicate things further, virtually all German heavy industry was in the strategic Ruhr valley; with most factories in western cities like Essen, Dortmund and Bochum. Alongside this, most of Germany’s raw materials such as coal and iron ore for industrial production were also located in the west, close to the Rhine River, a strategic artery connecting this heavy industry to the world’s shipping lanes.

So, when the victorious Western Allies tore up the Potsdam Agreement and formed the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) in 1949, the GDR was already in a weaker position. This is before you consider any of the other disadvantages faced by the East. Chief among those was the West’s breaking of the Morgenthau Agreement; where the introduction of a new West German currency instantly devalued the East German currency. The fact the West German economy was being propped up by the US Marshall plan— the policy by which the US would provide enormous loans and grants, in exchange for host countries surrendering sovereignty over their own economic policies— further exasperated the inequality between the German states.

The newly formed Socialist Unity Party had several enormous problems and limited options on how to deal with them. If the growing disparity in conditions from East and West due to geography and foreign intervention wasn’t bad enough, the FRG was also viciously anti-communist and belligerent towards the East. This hostility is unsurprising, given the West German government was largely made up of ex-Nazi’s and their collaborators, whilst the Eastern government was largely made up of concentration camp survivors, resistance fighters and exiles. For example, the first FRG Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, was a ‘centrist’ liberal who, a decade prior, entered a coalition government with Hitler in 1932. Beyond the multitude of ex-Nazi officers and officials filling roles in the newly formed NATO alliance and West German courts, the commander of the West German army prior to the construction of the Berlin Wall was Adolf Heusinger. A member of the German high command during the war, he was so close to Hitler (both figuratively and literally) that he nearly died next to him in the failed assassination attempt of 20 July 1944.

In contrast, the first East German leader was Walter Ulbricht, an exile forced to flee Germany when the Nazis took power. Erich Honecker, his successor, was a concentration camp survivor. Ernst Wollweber, one of the original SED politburo members during the genesis of the GDR was a leading militant, organising left wing paramilitary fighters on the streets of Germany during the 1920s and 30s, actions for which he was tried for high treason.

During the first decade of the existence of the East and West German states, these conditions of aggression and inequality were exacerbated as time went on. In Berlin, West German citizens could literally cross over to the East, purchase state-subsidised goods, walk back over to the West and either consume or sell said items for a mark-up, further bleeding the weaker East German economy. Furthermore, citizens could be educated in the GDR for free, then be recruited by American-subsidised West German businesses with the attractions of higher wages and living standards offered by the more developed FRG. This resulted not only in the east being further plundered in subsidising a highly educated West German workforce, but also the catastrophic brain drain that an already-shattered country could ill afford. This, combined with predatory anti-communist propaganda being fed into the East by the West German government and their CIA allies via the predecessor to Radio Free Europe, resulted in as much as 10% of the East German population emigrating west in the decade following the reconstruction of Germany.

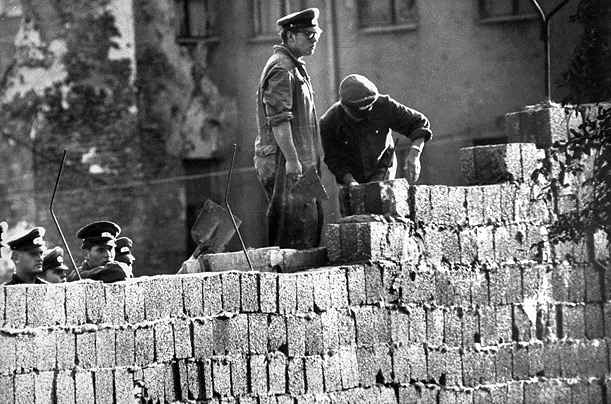

The decision to build the Berlin Wall came ultimately due to a combination of factors: relentless espionage, propaganda, sabotage and, more alarmingly, recently uncovered plans detailing a potential West German invasion of the east. The plan, codenamed Operation Deco II, consisted of plans to use West Berlin as a staging ground deep within enemy territory to decapitate the East German government and swifty annex the country.

In summary, for the first 12 years of its existence, the GDR was subject to aggression from the FRG, a country largely led by unpunished nazi criminals and collaborators, with an economy supercharged by American investment at the cost of any real semblance of economic sovereignty. They were also subject to industrial and military espionage and sabotage carried out by hundreds of Western spies who found it almost comically easy to cross into East Germany via the open border inside Berlin. Material and historical disadvantages also played a part, with the east suffering greater damage from the war alongside its isolation from the majority of Germany’s major trade routes, natural resources and heavy industry. Finally, the GDR was subject to a relentless propaganda war funded by the US’ comparatively endless supply of resources.

With all of this, any reasonable socialist, and indeed the SED themselves knew something drastic had to be done to protect their socialist experiment from internal meddling and external threats.

And so the Wall was built, and with it came an excellent opportunity for the West to construct a nightmarish narrative of desperate Germans flooding in from the East, braving barbed wire and machine guns for a chance at freedom. Perhaps unsurprising, this was staggeringly far from the truth. In the 28 years the Wall was up, Western estimates claim 136 deaths on the Wall. However, it’s also estimated around 10% of that figure were East German border guards, murdered by escaping Western spies. Virtually all these deaths occurred in the first 5 years of the construction of the Wall before it was properly fortified, so much so that in the years 1976-1989, approximately 40 people died in a 13-year span. For comparison, in 1976, a single US-sponsored terrorist attack on Cuban Airlines Flight 455, murdered 74 people. There is a sense of irony when assessing the Western narrative of East Germany being some dystopia, when compared to the callous brutality perpetrated by the Western powers at the exact same time.

In 1989, the Wall fell and the GDR’s degradation into capitalism began. While the protest movements that shook the country were a minority in terms of the population, of which many hoped for increased openness yet the retention of socialism, there was undeniably a mood for change and an optimism for the future. Unfortunately for the citizens of the East, they would soon come to learn that their free movement and increased consumer choice would come at a severe cost.

On reunification day 3 October 1990, the property of the various mass organisations of the former GDR, including the SED, their youth league, various affiliated trade unions, student’s and women’s unions were confiscated, effectively annihilating the organised workers movement in the country at once and with it any chance at substantive resistance to what was to come.

In June 1990, the conservative dominated Volkskammer (east German Parliament) created the Treuhandanstalt to handle the swift dissolution of the East German state. In a matter of months over 8,500 state owned companies, employing over four million people were flogged off in a fire sale. The meat of the East German economy, built by and owned by the people of the GDR, was sold out from under them practically overnight. Originally, this process was framed as a handover of the companies from the state into the hands of the people who had built them. In reality, over 85% of these companies were sold to West Germans. The old East German commitment to full employment was relegated to history, as 80% of all agricultural workers lost their jobs, alongside over 75,000 educators. Over one million degree-educated professionals became unemployed, representing the biggest proportion of unemployed graduates on the planet.

To make matters worse for the largely unemployed East Germans, they were stripped of the human rights they had enjoyed for years such as free childcare, extremely low rent and the aforementioned guaranteed employment. The final kick in the teeth came in the form of a hastily conceived currency union. East and West German Marks were pegged at an equal value, inflating the value of the eastern currency by more than 4.5 times in an instant, making the GDR export market collapse almost instantly.

Since the calamity of the 1990s, the federal states that make up the former East Germany remain on average 20% poorer than their Western counterparts. These conditions discussed above, and the vacuum left by the socialist state have led to a rightward drift in the political situation of the region. The people of the former East Germany, abandoned and left to stagnate by their new capitalist rulers, and with large scale communist movements long destroyed, threw their electoral support behind far-right parties. This trend has continued even 30 years since the reunification, as recent victories by the right wing AfD demonstrate whilst the milquetoast Die Linke, technically a successor to the SED, albeit now a democratic socialist party offering no real radical change, struggles to break 5% in the national polls.

Most of the old residents of Berlin are also slowly being priced-out of their homes and the population of the former East is still stagnating despite 3 decades free of sanctions. As the rest of Germany steadily grows, the old GDR states have remained at pre-1989 population levels.

There’s a common saying among former East Germans, particularly socialists, and that’s that West Germany didn’t unify with the East: it annexed it. Given the nature of the reunification and the nature of the German state today, it’s difficult to disagree. Reunification implies compromise and coming together; instead, the East German economy was destroyed, as was their government, their laws, their army, their police, most of their academia, all their tools and property of state, and even their history. Instead of these things merging with their Western counterparts, they were replaced by them.

Modern day Germany has a vested interest in vilifying the legacy of the GDR, because the success of that alternative to capitalism in living memory is an inconvenient truth to say the least. Despite the full force of the German state and media trying to relegate the GDR to little more than another authoritarian stain on German history, as another Nazi Germany, nostalgia for the GDR days, Ostalgie, remains persistent among those that lived there. The DKP, the successor organisation to the old Communist Party of Germany, is undergoing a renaissance. Experiencing tremendous growth, particularly among the youth born after reunification, the DKP has shown workers in Germany are rejecting the neoliberal ‘freedoms’ to be unemployed, homeless, exploited and indebted, and embracing class struggle. They have rejected the established narrative of ‘the failure of socialism’ and despite catastrophic defeats in Europe in living memory, the European communist movement survived and is once again growing. Unlike what our friends in the halls of parliaments across Europe would like to believe, it’s not over. The spectre of Communism haunts Europe once more.

Chris Cargill is a member of the Young Communist League’s Edinburgh branch