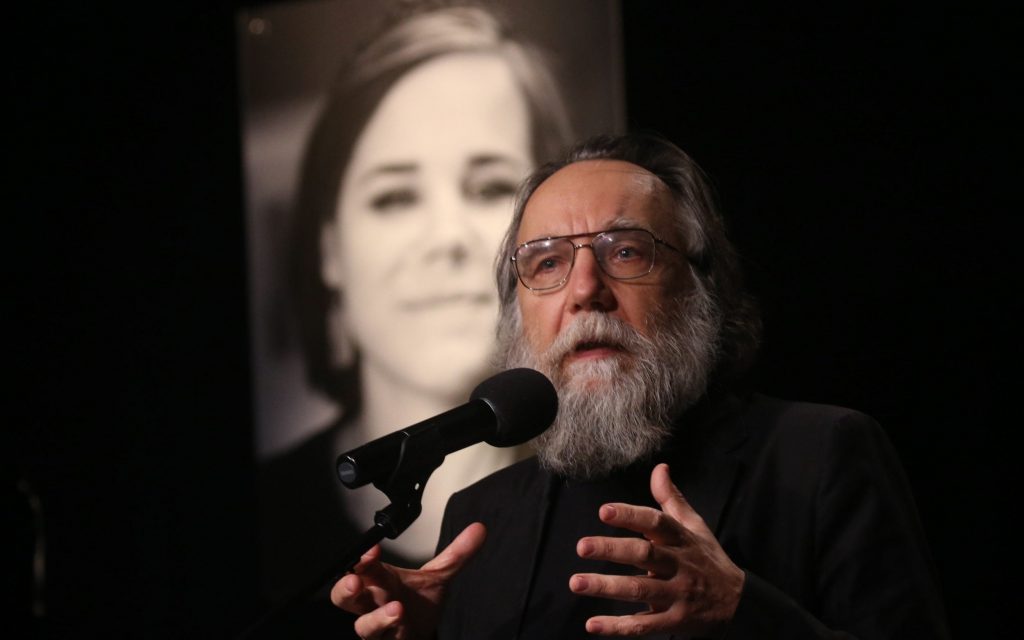

On 20 August, around 21:00 local time, the Russian-state journalist Darya Dugina was killed in a remotely detonated car bombing, as she drove home through Moscow. She was 29 years old. Darya was the daughter of ultranationalist philosopher Aleksandr Dugin, the so-called ‘guru’ of Vladimir Putin, whose car she was driving before her death. Darya had attended the Tradition ‘music and literary’ festival with her father earlier that day, and it appears they were expected to leave the gathering together, until Dugin took a different car at the last minute.

The Russian intelligence service, the FSB, claimed to have identified a suspect. They allege a Ukrainian national, Natalia Vovk, was employed in some capacity by the Ukrainian secret service. She supposedly entered Russia, with her 12 year-old daughter, in a silver Mini Cooper bearing Donetsk People’s Republic number plates. She then switched to a Kazakhstani plate after moving into a flat in the vicinity of Darya’s Moscow residence.

There, she allegedly stalked Darya for one month before the car bombing, whereupon she changed to a Ukrainian number plate and fled to Estonia. Later, the FSB would name a second ‘accomplice’, Bohdan Tsyganenko- another ‘Ukrainian terrorist’, who allegedly helped Vovk assemble the explosive device that killed Darya.

In the aftermath, discussion of which actors sanctioned this assassination shaped a purely speculative discussion. Some even tried to claim it as an accomplishment of the ‘National Republican Army’, a clearly fictious ‘resistance group’ in Russia. However, recent reports indicate United States intelligence officials recently chided Ukraine for arranging the killing without consulting with them. They claim they would have opposed the hit, fearing it would invite Moscow to retaliate on Ukrainian officials. Ukraine still officially denies any involvement.

The US officials also relayed their own assessment of the car bombing, that has lent further credibility to the general assumption most made as soon as the fiery images were seen across social media. Darya was not the main target of the assassination.

Yes, by all accounts, she was a regime-journalist who vehemently supported the invasion of Ukraine- as well as professionally manufacturing consent for it among the Russian public. That certainly makes you some enemies in Kiev, but that alone is hardly exceptional to her of all reporters in Russia. However, her much more infamous father, an occasional bogeyman in the Western media, would have made for a noteworthy assassination. To understand why Darya was killed, we must first introduce ourselves to the mysterious life and works of her father.

Aleksandr Dugin is a morbidly fascinating, contradictory figure: a dissident son of minor nomenklatura; a half-blind scholar posing with a rifle and a missile launcher in South Ossetia; a rambling, multilingual academic surrounded by punks and skinheads. Disregarding him as a mere far-right oddity would belie his true influence, but it is equally valid to say his characterisation as some nefarious ‘Rasputin-like’ adviser is also wildly inaccurate.

Born in 1962 to a father of high rank in the Soviet GRU military intelligence agency, and a doctor mother, Dugin was nonetheless an anti-communist from his youth. He indulged a juvenile penchant for occultist, neonazi and ultranationalist drivel with relative impunity from the authorities, owing to his family connections. That same nepotism also allowed him to regularly visit the Lenin Library archives, accessing a horde of banned literature.

Dugin spent his time in the late 1980s travelling around Western Europe, meeting the leaders of the French and Belgian ‘New Right’, including Benoist. At this stage in his life he began to develop as a far-right theorist, incorporating Traditionalism into his philosophy, and the need for an anti-communist, anti-liberal insurgent conservative political revolution.

At the death of the Soviet Union, the end of that spectacular Bolshevik Revolution, the despised Yeltsin government completed the necrogenesis of the capitalist Russian Federation. A combination of liberal capitalists, gangsters and Western corporations ransacked the country. The results were cataclysmic: personal savings evaporated overnight; the ‘state monopolies’ were plutocratically doled out to a handful of oligarchs; male life expectancy, which had steadily climbed to 64 by 1990 dropped to 57 by 1994. In short, Russian society transformed from one of practically perfect equality- everyone had a house, many had personal cars, and the most privileged echelon had drivers- to one of a handful of billionaires and impoverished millions, in the space of a few years.

Equally egregious was the crime of fracturing a united, multi-cultural USSR into bickering ethnic states. The horror of nationalistic, fratricidal strife plagued the new post-Soviet world. Against this backdrop of calamity and bitter immiseration, a multitude of new political movements and parties sprouted everywhere, as Russia’s place in the world looked uncertain.

Two years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Dugin was a founding member of the National Bolshevik Party, led by the flamboyant demagogue Eduard Limonov. The NBP sought to amalgamate the fundamentally opposed ideologies of Nazism and Communism, in order to ‘unite the two great opponents of Liberalism’. He and Limonov would cut peculiar figures for the NBP, erudite and refined writers leading crowds of subcultural, brutish youths flaunting outrageous nazi-style flags, with the swastika replaced with a hammer-and-sickle.

Dugin would part ways with Limonov and the NBP in 1997, as he published his most famous book, The Foundations of Geopolitics. The text gives a comprehensive outline of his ‘vision’ for a reinvigorated Russia, asserting herself on the world stage. He gives the specifics of how Moscow can make strategic alliances with Berlin, Tokyo, and Tehran to assemble complementary spheres of influence. Such a quadrumvirate, Dugin believes, would isolate the common ‘Atlanticist foe’ of the United States of America and secure Russian hegemony over the Eurasian landmass.

It’s very easy to assess the book as formative to contemporary Russian foreign policy; some of it can even read like prophecy. For example, in part 5, chapter 5, section 6 ‘Geopolitical Decomposition of Ukraine’, he writes:

“The continued existence of unitary Ukraine is unacceptable. This territory should be divided into several zones corresponding to the gamut of geopolitical and ethnocultural realities.

Eastern Ukraine (everything that lies east of the Dnieper from Chernigov to the Sea of Azov) is a compactly populated territory with a predominance of the Great Russian ethnic group and the Orthodox Little Russian population. All this territory is certainly close to Russia, culturally, historically, ethnically, religiously connected with it. This well-developed, technically developed region may well constitute an independent geopolitical region, with broad autonomy, but in an unconditional and strongest alliance with Moscow.”

It’s tempting to draw parallels between Foundations and the imperialist ambitions of the Russian state now, and judge Dugin as some nefarious adviser of President Putin. But aside from the admittedly sinister resonance of his most famous book, is there any real evidence of Dugin’s alleged éminence grise status?

Often characterised as ‘Putin’s brain’ in the West, most reports on Dugin and his shadowy ties to the Russian President will feature separate photographs of himself and Putin. Apparently, no photographs of the two men together exist, having seemingly never actually met, nor even been in the same room together. For comparison, George Galloway is evidently in more frequent physical contact with Putin than Dugin.

An oft-repeated factoid about Dugin’s influence is the apparent adoption of his Foundations of Geopolitics by the Russian state. During the annexation of Crimea in 2014, it was allegedly promoted as part of the Russian military’s reading-list. No primary sources actually confirm this to be true. Dugin has been rumoured to have worked with Russian military officials when writing his Foundations, and publicly praised the formation of a geopolitics course on the Russian Military curriculum, in a blogpost back in 2004.

Still, let’s be charitable, for the sake of argument, and presume his book was on the reading list in 2014. Just as quickly as his writings were reportedly endorsed, the full annexation of the so-called ‘people’s republics’ in Eastern Ukraine was ruled out for the time. Almost concurrently, Dugin torched his academic career at Moscow State University, being sacked for advocating escalating violence towards Ukraine on social media. Hardly befitting a man who holds a clandestine power over the Kremlin, is it?

In 2017, Dugin would further demonstrate the distance between himself and the President. He publicly criticised Putin in a interview, claiming he held a flawed worldview:

“I think that even he doesn’t understand what he’s saying because now he’s a liberal, now a conservative; now he’s for sovereignty, now for globalism, and now against globalism.”

Finally, now that the world has seen the revanchist Russia that Dugin wants, is there any major cues taken from his writing that Putin appears to be following? In short, no. The recent invasion of Ukraine has seen Europe’s ruling class turn to the United States for fuel and manufacturing, in addition to giving the American military ‘thalassocracy’ a significant fillip, as hitherto neutral nations like Sweden and Finland start making overtures to join NATO. The ‘Moscow-Berlin axis’ Dugin theorised appears inauspicious for the time being.

In the East, Russia has been diplomatically shunned by Japan, nipping any kind of ‘Moscow-Tokyo axis’ in the bud for the foreseeable. Exacerbating the goals of Foundations is the increasing dependence upon China as an ally rather than a rival to be isolated and undermined. Dugin wrote about destabilising Xinjiang, Tibet and Manchuria regions away from the mainland Chinese government, providing a ‘buffer zone’ to curtail Chinese interference in Siberia and Central Asia, which is considered ‘Russia’s backyard’.

Since the invasion of Ukraine however, the reverse seems to be happening. Russia has only strengthened its ties with China, whilst evidently failing to enforce its hegemony on the Central Asian states, as the emergent Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan border conflict would indicate. It remains to be seen if and how China will capitalise on the situation; its interests in the region with respect to the Belt and Road Initiative being of tremendous import.

To the South, there is a similar divergence in strategy from Foundations. Russia has effectively gifted Turkey with the role of regional mediator, after the grain shipment deals. This, in concert with the perceived Russian military weakness as the ‘special military operation’ drags on into the winter, has emboldened Azerbaijan to resume violent hostilities against Armenia, with Ankara’s blessing. All of these combined would be a setback for any ‘Moscow-Tehran axis’.

But as I said earlier, we cannot merely write Dugin off as a mere curio for the West. In 2015, the already-strained Russo-Turkish relations had soured after a Russian warplane had been shot down by the Turkish military. Inexplicably, Dugin turns up in this moment of crisis, a middleman for diplomatic repair between the two countries. This sober act of realpolitik sits in stark contrast to his apostrophising of Turkey in Foundations of Geopolitics: a hostile NATO member with an innate enmity towards Russia.

Dugin is, fundamentally, a far-right intellectual with an impenetrably esoteric philosophy. One could list his darkly eccentric beliefs, such as advocating the shutdown of the Internet, the removal of biology and chemistry from school education; the eminently post-modern idea that there is such things as ‘Russian truth’ and ‘American truth’ and no such thing as absolute truth.

The crux of his philosophy is Traditionalism. This is the utterly demented belief that at one stage in ancient history, mankind was guided by an actual ‘true religion’ referred to as ‘the Tradition’. At some stage, this Tradition collapsed, and sundered into the various major faiths of today. Traditionalists believe fragments of its insights can be found in each of those religions. By immersing themselves in Christianity, Islam etc. the Traditionalists seek to rediscover enough mystical wisdom to reconstruct the Tradition.

The core concepts of Traditionalism are, firstly, that time is non-linear. Instead, history is a cycle of constant decline, interrupted by a periodic golden age, which resets the state of decline. Secondly, the idea of a spiritual, social hierarchy. Hinduism is particularly valued by Traditionalists, convinced its antiquity places it closest to the Tradition than most other religions. The Hindu practice of the caste system- raising a priestly, enlightened Brahmin caste above the gradually earthly and unclean masses, according to the deranged assessment of Traditionalists, confers a mystical virtue to stratification.

Here’s a portentous anecdote: according to the mother to his first child and partner at the time, in his early-twenties, Dugin procured a copy of Heidegger’s Being and Time. The work was in microfilm format, as opposed to print, and so required a compatible device to be viewed. Undeterred, he somehow jury-rigged a children’s toy for projecting simple picture-stories, to display the microfilm text. The result was of abysmal quality: extremely dim, poorly resolved, and mirrored.

Staggeringly, Dugin sat in the dark, straining his eyes to read (in print metrics) 500 pages of abstruse philosophy, backwards; damaging his eyesight permanently in the process. That trade of sensory faculty for idealist wisdom might well be a metaphor for Dugin’s beliefs. For him and his compatriots, the spiritual, metaphysical virtue of the world is in constant struggle with the ‘illusion’ of material reality.

It goes without saying his worldview is inherently anti-communist, whilst also opposed to liberalism. Such a formulation has certainly helped him catch the attention of sections of the European and American far-right, looking to Russia as a bulwark against the ‘cosmopolitan degeneracy’ of the West. Therein lies the true philosophical influence of Aleksandr Dugin: he organises internationally, oscillating along the periphery of state power whenever he can make himself useful. Occasionally an academic, occasionally a political commentator, occasionally an unofficial ambassador.

At a conference in Rome in 2018, Dugin met a fellow high-profile Traditionalist, former advisor to President Trump, Steve Bannon. The two disagreed on whether to vilify the United States (Dugin) or China (Bannon) as the great destructive enemy of conservative values, much to Bannon’s frustration. Both men could be said to share a vaguely similar role in their respective countries: relatively obscure political players, who gain some momentary influence. But as Bannon fell out of favour with Trump, and slipped out of relevance soon after, Dugin remains at the boundaries of power. As soon as you write him of as a trivial character, suddenly you see him over Twitter, frozen and distraught amongst flaming wreckage; an astonishing moment of unimaginable grief, distributed for the world to leer at.

He indubitably holds some kind of value for the Russian regime- a political thinker who can paint the actions of the state in a grand narrative about geopolitics to exonerate thousands of people being slaughtered in a ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. Dugin even eulogised his own murdered daughter as a ‘martyr’ for the Russian invasion of Ukraine. He’s not some ‘guru’ of Vladimir Putin’s; he’s a calculated fanatic.

Valorised by a small readership, largely from abroad, Dugin is essentially a Nick Land or Curtis Yarvin character, with the additional, orientalist ‘mystique’ of hailing from Russia. He clearly has the ear of some officials, sympathetic to his outspoken political views, and scores odd jobs from the government with perplexing alacrity. But for Western media to claim he is the ‘philosopher’ of Vladimir Putin would be like Sputnik or Russia Today ludicrously reporting Dominic Cummings to be the ‘philosopher’ of Liz Truss.

Currently, the capitalist class of Russia has myriad motivations for war with Ukraine. A figure like Dugin can find some success whilst his and the state’s interests appear to align. But treating him as hyperbolically influential in the Russian regime is to put ourselves in a conspiratorial mindset. By all means, communists should be analysing and discussing far-right ideologies, including that of Dugin’s, in order to understand their allure and how to riposte them. But just because Western media portray him as the ‘brain’ of Putin, doesn’t mean we should join the vulgar, Twitter anti-imperialists lionising him as a ‘counter-hegemon’. To do so is not simply an embarrassment: it is severing ourselves from reality, and embracing the kind of mysticism the likes of Aleksandr Dugin cultivate.

James Meechan, is Challenge’s Features Editor