Over 30 years on from the dissolution of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), British communism has reached a new juncture, characterised by defiance of the anti-communist myths of the past and faith that Marxism-Leninism is the political path best suited to turning the looming contradictions in contemporary capitalism – climate collapse and rapidly-rising inequality – into a revolution.

The end of the beginning

November 1991 marked the end of the CPGB. A party once feared by the British establishment was disbanded and its assets transferred to Democratic Left, a mere pressure group, by the more hardline section of the Eurocommunist political tendency who controlled the leadership – the Young Communist League (YCL) had already been illegitimately liquidated in 1989.

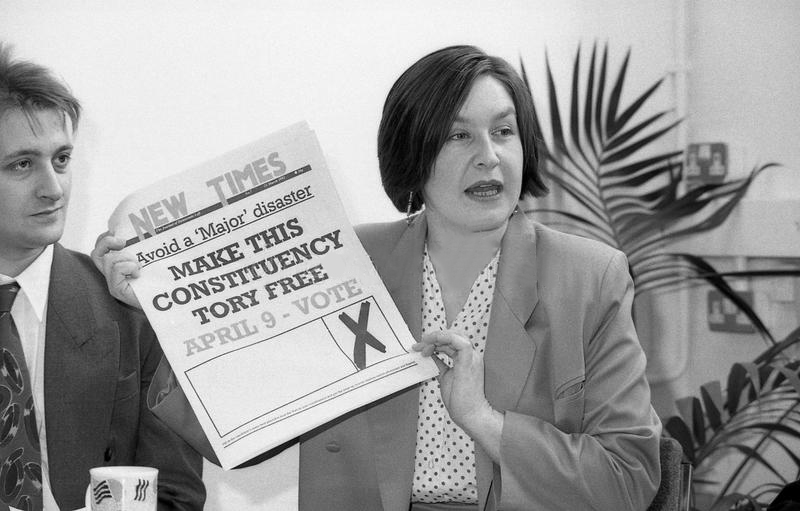

The dissolution of both the CPGB and YCL were part a paradigmatic shift in the Western world following the collapse of the USSR and Eastern Block that saw many on the left shift their support from the seemingly archaic and discredited ideology of Marxism-Leninism towards broadly liberal ideas around humanitarianism, namely that of think-tanks and NGOs. In 1991, the final CPGB general secretary Nina Temple proclaimed: “The internationalism of the 1990s will be as much informed by Greenpeace and Oxfam, as communism once was by Marx and Engels.”

The liquidationists followed the mainstream, establishment view that communism was a failed experiment that had not been able to compete with the dynamism and creativity of capitalism. The retreat from materialist analysis and class struggle amongst the dominant faction of the CPGB had been clear for some time. Internal opposition towards elements of Marxism-Leninism within the CPGB had existed as far back as the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. By 1991, the majority were in favour of dissolution, whilst a minority of organised Marxist-Leninists in the Party who stayed on until the bitter end went on to found Communist Liaison and the Communist Trade Unionists group.

In reaction to the Eurocommunist leadership’s disavowal of the basics of Marxism, the Communist Party of Britain (CPB) had been founded in 1988. Made up of former members of the CPGB who had been expelled, and later ushering in the remaining Marxist-Leninist members of the original party after its dissolution, the CPB became the de facto Communist Party, a continuation of the party founded in 1920, with the Democratic Left crowd having vacated this space entirely.

Under extreme pressure, with most of its property and assets effectively stolen, and struggling against widely-held misconceptions about communism that even supposed Marxists now saw as common sense, the CPB refused to surrender their politics to appease triumphal liberals and fought to defend the influence of communism by holding onto their networks within the labour movement, maintaining the Morning Star daily newspaper, rebuilding an openly communist presence in political movements and re-founding the YCL.

Being a Marxist-Leninist in Britain in the period between 1991 and the financial crisis in 2008 was not an easy task – but now, over 30 years on from this rebirth, the fruits of this ideological commitment by older comrades have begun to flower with a new generation of members in both the CPB and YCL, solidifying Marxism-Leninism’s relevance in contemporary British politics.

In 2021 the CPB’s 56th party congress – counting, as it should, the congresses of the original CPGB as its own – was its biggest since the 1980s, with party membership increasing by 63% that year alone. The YCL’s growth has also been rapid, going from 100 members in 2016 to over 500 in 2021. How has this resurgence come about?

Structural factors

In 2020 the Communist Party’s programme, Britain’s Road to Socialism was updated to include a new section on the general crisis of capitalism explaining that the long period of economic growth for the West following the Second World War had finally ended. This is the reality we live in. It is a cliche that every generation of young people think they have it worse than those before them, but if you were born in the last 30 years this is actually true. Real wages have been falling since the 1970s – the value of what we are paid at work will buy us less than it would have for generations before us. On top of that, the safety nets that existed until the 1980s have been removed – stable employment in nationalised industries, cheap and plentiful council housing, straightforward and non-punitive welfare at acceptable levels are all gone.

Instead, we find ourselves gouged by a myriad of spivs: our council swimming pool is now called Fitness Plus and costs £40 a month not 50p a visit; it’s cheaper to fly via Berlin than to catch a train from London to Scotland. Indignities both large and small that all add up to something much worse than a sting in our pockets – there’s less and less point in even trying, in believing in the economy as it is when there is less and less opportunity to achieve even a fraction of the security our parents had.

We are a generation who cannot be bought off by the Thatcherite promise that one day we will own our own home; when we spend on average a third of our income on rent, it’s impossible to save seriously – which means in a very material sense, it is impossible for us to keep faith in the system. We know we are paying off a mortgage – it’s just someone else’s.

For the generations of leftist youth that came before after the 1945 post-war settlement the system had a way out – bourgeoisification, becoming petty-bourgeois or ‘middle class’, via the universities. Our predecessors were able to turn their passion for knowledge about class oppression, Marxism, economics, politics and society into qualifications that gave them buy-in with the system, as well as a decent wage.

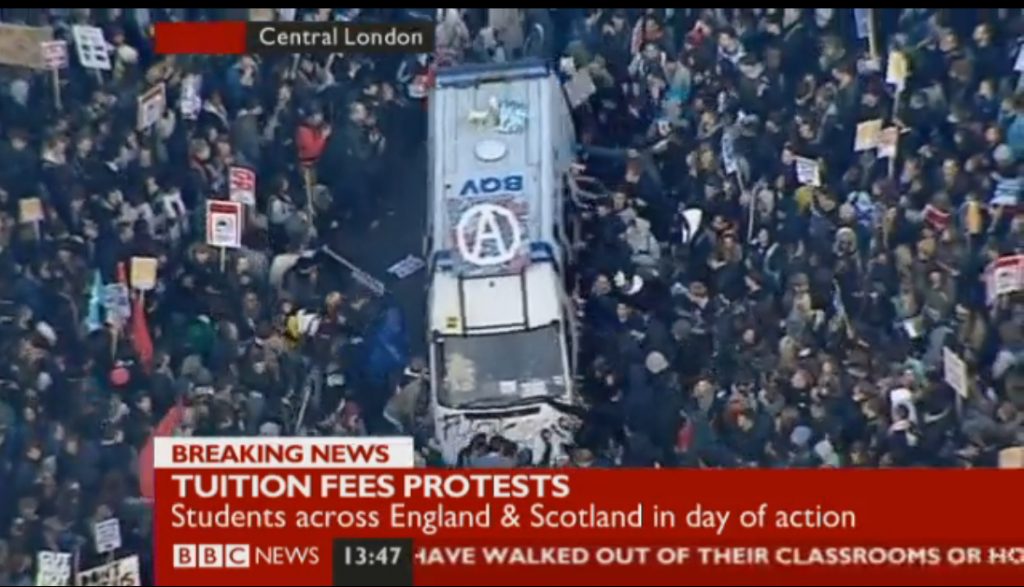

This tactic of middle-class expansion peaked in the early 2000s when just over half of young people attended some form of university, then crashed in the 2010s, not only due to the introduction of tuition fees but the growing realisation that the notion that a degree would deliver a middle-class life was a mirage – the middle class was being liquidated by neoliberalism, just like everything else, to fuel a society of extreme inequality.

In light of this all, capitalist democracy is an irrelevant circus, a soap opera that says almost nothing about the direction of society and our place within it. Its inability to respond to crises as local as the massive increase in families relying on foodbanks to those as big as climate change is obvious.

But why would this mean that Marxism-Leninism, the most maligned ideology, apparently grey and lifeless at best, or blood-drenched and brutally genocidal at worst, appear as an answer to these structural problems rather than “the alternatives?” The answer is the same in the current period as it was in the heyday of Marxism-Leninism between the 1920s and 1950s: the successes of Marxism-Leninism and the failures of everything else.

The 1990s and its ‘alternatives’: their turn next?

Although alternative, more liberal movements than Marxism-Leninism grew on the left after the collapse of official communism in 1990, they never came close to the size and penetration of the communist parties of the past. To discuss them is not to exaggerate their importance, but to look at why this is, which in turn will help us understand why Marxism-Leninism is making a comeback.

By far the biggest Marxist current in the UK by 1990 was Trotskyism, which, whatever criticisms people may have, adheres to a Leninist structure – but opposed the USSR and all the other states that Marxist Leninists refer to as the ‘Actually Existing Socialist’ (AES) such as China, Cuba, the DPRK, Vietnam and Laos today, and the USSR, Hungary, Poland, DDR/East Germany etc. up until around 1990.

The major UK Trotskyist parties celebrated the collapse of the USSR and eastern block and declared the other AES countries doomed to their own ‘democratic revolutions’ soon. The mentality was that the system of one-party socialist rule in all AES countries had “failed,” vindicating Soviet dissident Leon Trotsky at last – and that after ‘Stalinism’ it would be “their turn next.”

From a liberal-left, anti-communist perspective – why not? Socialism without the horrible police state clamping down on poets and dreamers, surely that would be more popular than official communism ever was? Instead, all Trotskyist predictions were wrong – from the idea that the remaining AES countries would soon collapse (none did) to the idea that the counter-revolution in the USSR and Eastern Europe were in fact going to lead to better and deeper socialism (every single one has to lead to capitalism, in some cases civil war, ethnic cleansing, and far-right governments).

On the domestic front, other fanciful Trotskyist predictions or assumptions failed to materialise, draining their recruits’ reserves of enthusiasm and burning their credibility with everyone else – feminism, ecology and above all anti-racism failed to ‘turn to the left’ and bolster their ranks. Capitalism continued to boom well past their predictions, all the way until 2008. The unions continued to decline in numbers and power, and crucially, assaults on the welfare state and worker’s rights failed to create the predicted fightback, which was, according to them, always just around the corner.

Although the class struggle raged in this period, the proletarian side was still in decline, as was support for socialism. Trotskyism failed to grow significantly along with the left and unions in general. This debunked the widely-held belief that ‘Stalinism’ had been holding them back, by giving socialism a bad name and directly sabotaging Trotskyism’s radical plans for leadership of the labour movement.

Despite a shot in the arm from the anti-war movement around 2003 to 2005, their membership continued to decline from its high point in the 1970s, and their desperate turn to identity politics to seduce student members only created the ground for later problems when the reality of Trotskyist-style democratic centralism crashed against the festival of liberation, freedom, and self-actualisation they had promised their young wards.

Between 2010 and 2015 Trotskyism entered its most profound and rapid decline, an existential crisis that saw numerous organisations drop to double digits or disband. Corbyn’s Labour essentially poached their remaining demographic – along with many other social strata – for good.

But what about the anti-capitalist ‘movement of movements’ that sprung from radical environmentalism (lots of useful ideas here), neo-anarchism and postmodern-left ideas that eschew labels (of no use at all – actively harmful)? And if Trotskyism was a variant of the “failed” state-socialist, authoritarian project, shouldn’t the alternative left have a lot more appeal and a lot more to analyse? In short, no and also no.

To give it its due, the alternative left after 1990 did make an impact at its two high points – anti-globalisation summit crashing, like the anti-WTO protests in Seattle 1999, and the Occupy movement of 2011. These, directly and indirectly, politicised hundreds of thousands of people who would go on to be class fighters – in part because of the soft-touch they received in the liberal media and popular culture, selling thousands of books, newspapers and even films.

From the accessible reformism of Noam Chomsky and the outlandish anarchist anthropology of David Graeber to the highly academic autonomism of Bifo, and its associates Deleuze and Guattari, anti-state leftism does have a lot of ideas that might provoke and engage newcomers to the left; but it has little of anything else – looking at the lack of actual achievements of the 1990s and 2000s, beyond all the books and articles, shows this beyond any doubt.

It failed dramatically to demonstrate the worth of its supposed alternatives to majority voting and formal membership organisations run with discipline, aiming at state power. There is simply nothing to analyse concretely other than failed experiment after the failed experiment: they never “won” for long enough to govern (in whatever radical horizontal way they’d like to).

Now writing at a time when anti-state leftism of both postmodern and anarchist varieties has disappeared in Britain to pre-1960 levels, it is almost amazing to think how little an impression all those weird and wonderful ideas have left on the tactics and ideology of the left today, which has returned to the traditional pillars of either social democracy or Marxism. We do owe them a debt, however – they failed, so we don’t have to.

The successes of Marxism-Leninism

Although the internet was hailed as putting the final stake in the heart of ‘authoritarian socialism’ by providing a network for ‘horizontally organised’ anti-capitalism, in fact, the sudden deluge of free-flowing information not edited by capitalist media debunked myths propagated against communism that had been obscured or undermined in mainstream and even left-wing Western media too.

The internet changed all that, especially from the period known as ‘web 2.0’ when interactive, user-generated platforms such as blogging, vlogging, wikis, discussion boards etc. became accessible to anyone – we can measure the rapid growth of interest in Marxism-Leninism from roughly 2005.

Now, young people drawn to the glory and success of official communism for its numerous victories over capitalism could take a balanced view of its excesses and failures with reference sources from the time, the once-obscure writings of communist leaders and thinkers, and best of all, to people who had actually lived in the Eastern Bloc and USSR, via the internet. They could also hear from the same sources what had been amazing about state socialism in contrast to the nightmarish circumstances foisted upon them by the restoration of capitalism. People felt lied to, and over time, indignance at capitalist smears developed into full-blown support for communism.

This internet-enabled Marxism-Leninism was not limited to the nostalgia of course, as increasingly the surviving AES countries were accessible online too – you could now hear what China had to say about its politics or watch YouTube videos from socialists on their daily lives in Vietnam. The successes of Cuban medicine and the education system in Kerala were able to be broadcast worldwide, and the smaller successes of communist parties outside of power too.

It was now obvious to young people in the West that state socialism in the past and present was not simply a great system that delivered better health, better living standards, better stability, better equality, more leisure time and above all, meaning to life as a community rather than a mass of competing individuals – it was also obvious that state socialism and its overarching ideology of Marxism-Leninism was a living success whose global adherents numbered in the millions.

2015-2019: a sojourn in Social Democracy

Given the economic situation, it was natural that the last decade would see a resurgent left aiming at state power via elections in the West, with a significant and often dominant youth element – Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, Bernie Sanders in the US and Jeremy Corbyn in Britain. Although these were all left-to-liberal, reformist and non-Marxist projects, for the US and UK at least, they reflected a change so profound that most Marxist-Leninists correctly saw their potential for redefining politics permanently.

At the height of Corbyn’s popularity membership of the Labour Party reached 500k members. If the CPB and YCL had been opposed to LP in this era it would have critically discredited itself – instead, it did the opposite, and gained credibility in the eyes of future supporters and members. It was the CPB and YCL that correctly criticised Labour’s retreat on Brexit and instead endorsed ‘Lexit’, correctly argued that the new movement needed to be deepened beyond elections and embedded in organised struggle, and correctly defended Labour against the antisemitism smear campaign. Although other groups did some of these things, none did all of them.

Another important stance was the refusal to fold the CPB and YCL to become a clandestine entryist front within the Labour membership, despite the closeness of Corbyn to the CPB, Morning Star and associated parts of the left. This is due to the principled and ambitious stance of Britain’s Road to Socialism, which was almost uniquely suited to the moment: the BRS argues that due to its direct connection to the trade unions, the Labour Party is not simply a liberal party, and a left-led Labour government is a key stage in building socialism for the CPB. However, this is to be done alongside Labour, openly, by building a communist movement in the unions and society in general, by intervention not in Labour, but the class struggle itself.

When Labour failed in 2019 in quite a spectacular fashion, and a ruthless right-wing regained power, the CPB and YCL were vindicated and became a natural home for the Marxist contingent of former Labour supporters who had been radicalised – or re-radicalised – by Corbynism.

Now is the time to respectfully criticise failings of the Labour Party under Corbyn – the misunderstanding of the subversive nature of the culture wars and identity politics, the failure to be disciplined against traitors and bad-faith actors, the uneven social makeup of the new membership, the lack of actual community and industrial organising – and many other things. But the years 2015-2019 must be remembered for what they really represent; not a failure at all, but a huge leap forward in support for socialism and millions of Britons thinking seriously about what the left in power would look like. That cannot be forgotten – instead, we must go forward.

Cautiously optimistic: where do we go from here?

In the last 5 years, the YCL has experienced rapid expansion, an increasingly steep upward curve, a situation of exponential growth where greater numbers lead to greater ability to be active, leading to greater visibility and relevance – and a greater number of applicants. Obviously, this will reach a natural plateau at some point, but as we are still miles away from even having all the young people who identify as communists in our ranks, that plateau is not expected anytime soon.

Take the last year as an example of how YCL activity has itself played a key role in our growth. Foodbank collections were rolled out nationwide, giving our presence on the high streets a direct purpose with social good, and providing a jumping-off point to talk about poverty and class. In our Lanarkshire branch, this is developing into a food-growing co-op.

Challenge, has been relaunched online and its articles are being picked up by the wider left, an unprecedented rise in its reach, while our social media presence has drastically increased – in its first year our Instagram has gained 10,000 followers.

Our biggest congress since the 1980s was well organised with a high level of discipline and engagement, with passionate debate and tight votes reflecting a vibrant internal democracy. Considerations around atmosphere and presentation made sure it felt unlike the often slightly-awkward and apologetic meetings typical of the left and reflected the messaging throughout the year – that we were celebrating our 100th anniversary with outward displays of pride.

Our annual summer camp was a similar success, again, record attendance and all sessions and infrastructure confidently organised by the YCL alone. Sessions on workplace organising from our numerous workplace activists, reps and union full-timers reflected both the class make-up of the organisation and its focus on class struggle rather than movementism and fad-chasing.

Developing a visible communist presence on marches and memorials that is open and proud about our politics, both dignified and militant, rolled out nationally as policy, which has led to media attention from the Sun, the Daily Mail and the Independent to name a few. Our block in Glasgow during Cop26 was the largest of any political block on the march, and when it was attacked by the police the YCL gained national attention and widespread support from the unions, wider left and even those that fervently disagree with our politics. The following week saw a wave of applications.

None of this has been too ambitious or required fanatical dedication and full-time organisers – in fact, it’s been quite moderate in terms of the amount of activity we would like to achieve in future. What marks it out is that most of these kinds of activities and especially the style in which they were carried out has been absent from the left for at least a decade, and in some cases, absent from the Marxist left for far longer. There is no reason not to expect this year to be equally dynamic if not more so.

In the last 10 years we have seen numerous new communist groups and initiatives led by young people pop up and burn out, leaving almost nothing behind – we are deeply aware of those groups’ failings and the dangers we must avoid, and this influences our interest in being in a serious party with a long legacy and tradition to defend, rather than letting political, and as is more common in today’s left, personal problems define us instead of our commitment to building a unified communist movement.

So, while a rebirth of interest in Marxism-Leninism was likely given the factors discussed in the previous sections, the growth of one single organisation, which has already survived serious attempts to destroy it from within and without in the last year alone, was far from inevitable: the seriousness with which the current membership of the YCL have approached their tasks is a central factor in the group’s growth.

What the YCL lacks and now needs more of is campaigning targets and plans for longevity, as well a centralised system of ruthlessly evaluating our work. The wider YCL must continue to follow the example of our best branches and become campaigning groups in and of themselves, as well as be active in the existing class struggles.

We need to be ready to take action against social ills caused by capitalism in our areas – against anything from bad landlords, to army recruiters, predatory betting shops and loan shark companies, bailiffs, any new far-right groups, privatisers, exploitative bosses etc. – we will know our own territory best and must assess it properly to take action as part of the class, in its class interests.

At the same time, we must walk the fine line of providing social goods too, without becoming a prop for the system or doing charity work – in this task we should think about establishing institutions, sometimes physically with rented, occupied or even eventually owned spaces to provide facilities for ourselves to meet the demands of our fellow workers. Looking back at the history of the YCL and CPB, this would not be a first.

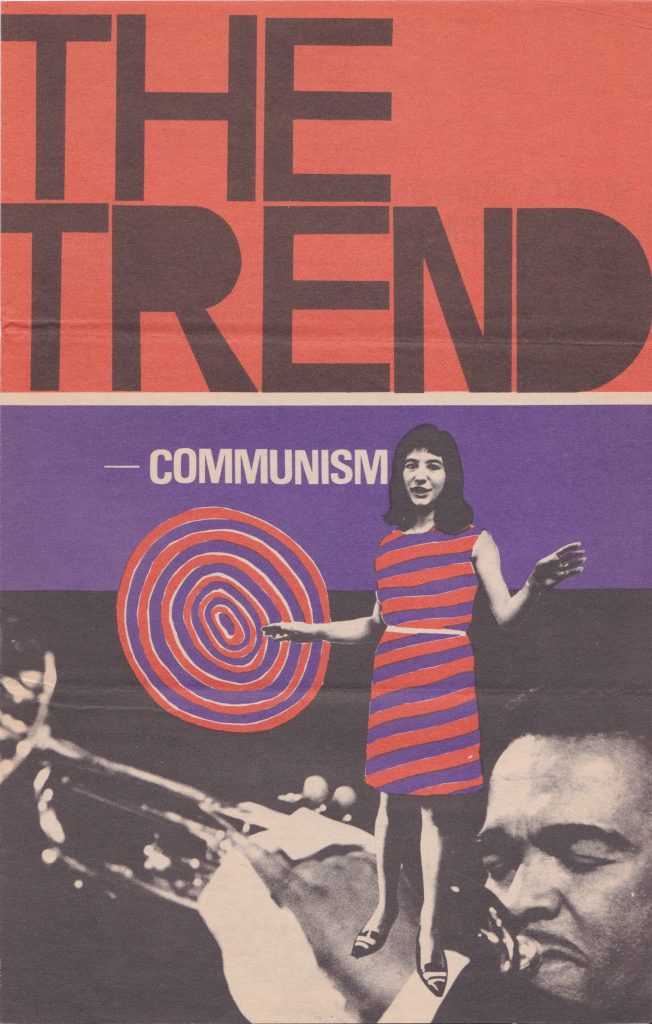

We have gained a lot of attention, but we must deepen our cultural presence – communism must continue to make headway into the social lives of youth. Given that in the 1967 the YCL’s Trend festival had The Kinks headline, notable musicians such as Pete Townshend from The Who became members, and The Beatles were interviewed in Challenge magazine – there is no reason why we shouldn’t aim beyond local cinema clubs, gigs, club nights, sports clubs and so on towards an annual music and politics festival, open to all.

Conclusion: socialism as a way of life

We have inherited a mighty tradition, and owe it to all the YCL and CP comrades who have come before us to continue to confound the critics and make our work more and more relevant to more and more young people – despite the massively changed political circumstances from the heyday of communism in Britain in the last century, we genuinely believe, given all the factors outlined here, that unapologetic Marxism-Leninism will become the guiding ideology and movement of this and the next generation of those who are ready to reject capitalism and go beyond sporadic rebellions to build strong socialist organisations.

The ideology and collective identity of the current YCL is summed up by our slogan “conquer your future.” We are not fixated on grievances, wounds, injustice and rebellion, we are focused on power as a goal – empowering each other as comrades and the communist movement itself to take an organic leadership role through its direct and successful intervention in the class struggle, embedded in the daily lives of the masses.

We intend to be involved for life, and the YCL is the first stage — the one that is naturally seen as being more radical. We cannot promise those in or about to join our ranks the fruits of socialism, but we can say that the skills we are learning and the comradeship we are gaining has materially improved our lives and – perhaps most of all – given us meaning and purpose in a world of neoliberal nihilism. We will live once, but our organisation has already lived 100 years: it is with immense pride that we can say, in time for its centenary year, the YCL is seizing its destiny once again.

“We have made the start. When, at what date and time, and the proletarians of which nation will complete this process is not important. The important thing is that the ice has been broken; the road is open, the way has been shown. – V. I. Lenin

Tomasz Nowak