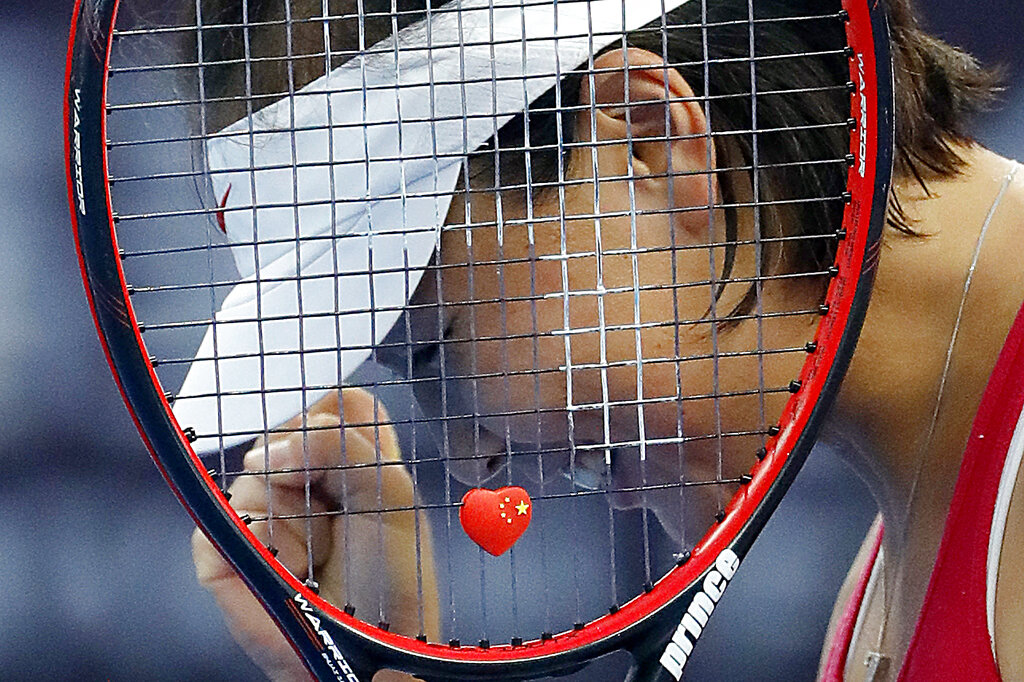

Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai has been everywhere in the news over the last month following a post on Chinese social media platform Weibo describing an emotionally abusive relationship with retired former vice premier Zhang Gaoli, which was promptly removed. Cruelly, many Western media outlets have chosen to use this post to exploit Peng at her most vulnerable, distorting her story and ignoring her wishes for privacy in order to further US political goals against the country she loves.

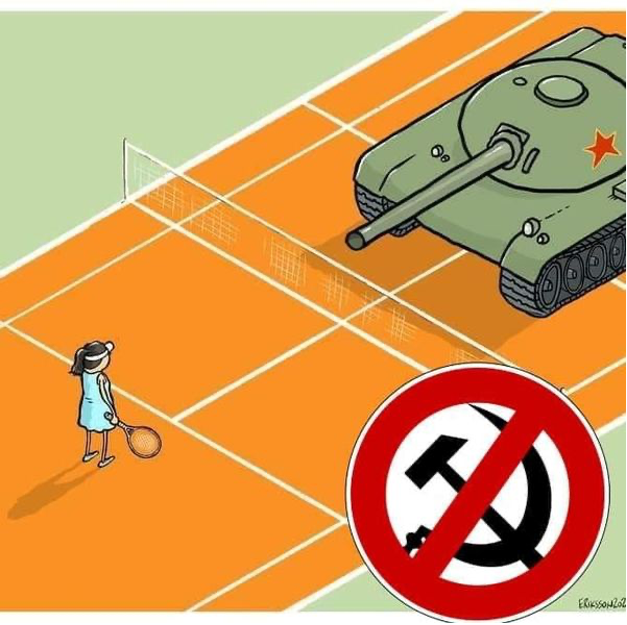

Her story has been transformed into a tale of state censorship, oppression, and violence. A #MeToo story to add wind to the sails of an ongoing campaign by the US and its vassal states to engage in a boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics. This is the latest in a long string of attacks in a worsening “New Cold War” against China, their biggest economic and ideological rival, which has led to a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes in the West.

So how has Western propaganda distorted her story in order to push their political goals, and how can we avoid falling for similar traps in the future? Let’s take the Peng Shuai case as an example to see how the media operates:

1. Find a victim (real or imagined)

In order to manufacture consent for a political intervention, be it a boycott of the Winter Games, economic sanctions, or even war, the West needs someone on whose behalf they are intervening, usually on the pretext of some human rights violation. This can be an individual (e.g., Peng Shuai), a group (e.g., Uyghur Muslims or Falun Gong supporters), or even an entire population (e.g., Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong, etc.) The victim’s oppression may be real, invented, or somewhere in between, but the intervention will always be attempted without any actual consideration of the victim’s wishes or wellbeing, and will usually be made hypocritically by countries with a long history of human rights abuses, colonialism, imperialism, and genocide. The victim will then be pitted against a villain, which in this case must not be Zhang Gaoli, but the entire Chinese state and the socialist system it represents.

Peng Shuai’s heartfelt confession online made her the perfect candidate for the latest in Western victim narratives. She is, after all, a victim, although Western coverage has been careful to distort key details of her case.

According to her statement, she and Zhang had had an on-and-off love affair which ended about 7 years ago when he was promoted to Xi Jinping’s Politburo Standing Committee, the highest governing body in China. Zhang is married, and it sounds as though the risk to his career from the affair caused him to break it off after his promotion, although they restarted it after his retirement. Because of their role as public representatives, Communist Party members in China are held to a much higher standard of conduct than ordinary citizens. If an official is discovered to have committed adultery, the Party’s internal disciplinary body, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) may punish them by demoting them or even expelling them from the Party.

About 3 years ago, after Zhang had retired, Peng says that their affair was rekindled with his wife’s knowledge, beginning with a tennis match between Zhang, his wife, and Peng, and an invitation to their house for dinner. At their home, Peng describes Zhang making several attempts throughout the day to pressure her into sex. She refuses twice, but then eventually agrees with a third person watching the door. What she describes in the lead up to this point is a state of distress and confusion, and a great deal of emotional manipulation and coercion from Zhang, who first tells her that he hates her, and then that he had never stopped thinking about her. Peng says that her eventual decision to sleep with him was partly “out of the affection she had for him seven years ago,” though from the allegation, he is clearly being emotionally abusive as well.

As they restart their relationship, Peng describes “opening up her heart” to him again during a period she remembers fondly, filled with long discussions about history and economics, and games of tennis, chess, and ping pong. She says he treated her well and that it felt like they were made for each other, but that she felt a growing misery and self-hatred from keeping their affair a secret from the public and her parents, from the snide comments made by his wife when they were alone, and from Zhang’s refusal to get a divorce to protect his reputation. Eventually it all becomes too much, which is probably what prompted her to make the post.

The statement is vague and confusing to read in places, which is why it’s been so open to interpretation and distortion by bad-faith actors. Having discussed her case with native Chinese speakers who had read the statement, their consensus was that it was more complicated than portrayed, emphasising the pair’s romantic history and their interpretation that it was Zhang’s status as a married official that put Peng off, rather than a lack of feelings. But if the allegations are true, it is clear that Zhang Gaoli abused his position and the power imbalance between them, and the emotional abuse and sexual coercion described should be unequivocally condemned.

2. Build a narrative (and keep shifting the goalposts)

Although there were only two pieces of evidence to draw from (Peng’s post and its removal), Western media worked to build a story around these two elements at breakneck speeds. Just days after the post was taken down, the media was playing on anti-Communist hysteria that the government had made her “disappear” due to her statement. Orwellian-style disappearances are a common accusation levelled at Communist governments, and we can remember a similar story concocted about Jack Ma, the former executive chairman and co-founder of Alibaba, when he made a speech in Shanghai advocating for the liberalisation of the Chinese economy. This of course turned out to be false.

In Peng’s case too, mounting evidence showed that she was actually just at home, possibly taking some time out of the spotlight after her revelation. This included the statement posted by CGTN, pictures of her at home shared on her WeChat account, pictures and videos shared by a friend of them at a restaurant together, and footage of her at the Junior Tennis Challenger Finals in Beijing. Soon, the evidence was seemingly undeniable, with a video call between Peng and the president and other members of the International Olympic Committee in which she assured them of her safety, asked them to respect her privacy, and invited them to have dinner with her when they met in Beijing. But did the Western press admit that they were wrong and seek to reassure their concerned audiences that she was OK? Of course not. They just changed their narratives to suit the new material.

As an example, a Guardian editorial alleged without evidence that all the proof of her safety was manufactured, that the call was made under duress, and that it didn’t actually matter whether she had disappeared or not because other people are supposedly disappeared by the Chinese government all the time. It then went on to attack the International Olympic Committee for confirming her safety, and back calls by Joe Biden and Liz Truss to boycott the Winter Games. Similar attempts at backpedalling and goalpost shifting were also used during reports on Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. When accusations of genocide were found to be baseless, some parts of the press doubled down on claims of a cultural genocide instead.

The media was also able to exploit the fact that the post was removed in order to reinforce their narrative of state repression. It’s no secret that Chinese censors can be a bit trigger-happy when it comes to removing politically sensitive material. After all, they recognise the capacity for Western governments to exploit these tools in order to spread false information, ferment discontent, or seed protest movements in their interests. They would also much prefer to handle complaints against the Party and carry out their investigations through the proper channels in accordance with the law, rather than through the court of public opinion.

Some commenters have suggested that since Zhang Gaoli was just a retired official, the government could have dealt with the scandal quicker and more effectively by doing so out in the open, and that by removing the post, they had shot themselves in the foot. That said, censorship did not stop Peng’s statement from circulating on private channels, and when the French embassy released a question concerning her safety on their Weibo account, the post was not removed. Instead, politically savvy Chinese commenters were quick to recognise another hypocritical media attack from the West, with top comments asking the embassy to address the 216,000 child victims of sexual abuse from the French Catholic Church since 1950.

3. Exploit the information barrier

We are often told that we must listen to women and victims, and yet despite this, very few articles on Peng’s case have actually included her full statement. Many articles have also selectively omitted important bits of context, such as the couple’s romantic history, her feelings for him, or her decision to restart their relationship.

When parts of the statement do appear, the translation has often been altered to imply physical force, rather than emotional coercion (which is bad enough). As an example, careful translation of the word bì “逼” as “force” (he forced me to sleep with him) detracts from its real meaning which skews more towards coercion or persuasion (he got me to sleep with him). As another example, a lot of reporting has emphasised the description of a person guarding the door, implying that they were preventing her from leaving, rather than keeping watch so that no one walked in. I hate being forced into the position of splitting hairs about the details of a sexual abuse case, but it’s clear that a lack of nuance is being used for malicious purposes.

The complexity of the Chinese language has meant that selective translation errors like this are common when pushing anti-China narratives. When they were invited to film at one of the rehabilitation and training centres in Xinjiang, the BBC deliberately mistranslated a statement from a participant to imply that he had been forced to go there against his will, rather than attending voluntarily. This is done with the assumption that the language barrier will mean that the audience won’t be able to check the source. Chinese and Western narratives are also separated by different social media platforms and search engines, making balanced research more difficult.

Regardless, Western propaganda has already been so successful at creating suspicion of China that most Chinese sources are dismissed out of hand. Chinese and Russian state media like CGTN and RT are presumed to be much less trustworthy than British state media like the BBC, and big tech social media platforms like Twitter play into this by attaching labels to Chinese and Russian outlets as “state-affiliated media” but not to outlets of US ally states. Because of this, all evidence that Peng is fine and well has been attacked for being manufactured or staged. When Uyghur Muslims were filmed celebrating Eid al-Fitr in the Xinjiang capital of Urumqi this year, US state propaganda outlet Radio Free Asia claimed that they were actually forced to do so by the state, banking on the fact that this claim would not be challenged. Similarly, many bloggers or social media commenters that challenge anti-China narratives online are often accused of being bots or paid propagandists.

4. Manufacture consent for political intervention

Following the media saturation of the Peng Shuai story, including more than 30 articles in the Guardian put out in November alone, there have been huge outcries from the public for a response. Social media users started by circulating the hashtag #WhereIsPengShuai, and soon other celebrities and tennis stars were adding their voices to the mix as well, with tweets of concern for Peng’s safety coming from Serena Williams, Naomi Osaka, and Andy Murray, among others.

Politicians and governments have made statements as well, hyping up the case and pushing the Olympic boycott. A few examples for the US include the spokesperson for the White House, Ted Cruz, and Mike Pompeo; while for the UK, there was the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office, Lisa Nandy, and Liz Truss. The office of Michelle Bachelet, the High Commissioner of the UN office for human rights, has also made a statement. A rally was even held for Peng Shuai in New York on 21st November calling for her safety, the same day that she had her video call with the IOC asking to be left alone.

Whether they had good intentions or not, all of these people were contributors to yet another coordinated propaganda attack on China, hyping up an invented human rights violation of state repression against a woman who did not consent.

Conclusion

Although he is retired, a proper investigation may still lead to discipline against Zhang Gaoli over what happened. Retired officials often have a ceremonial role in public affairs which he may no longer be entitled to, for example, or he may lose his Party membership. Peng may also choose to seek justice through the courts, since as previous cases in China have shown, not even high-up officials are above the law.

But ultimately, it is up to China to resolve this case on its own terms, and time spent badgering China on human rights would be much better spent tackling our own country’s terrible human rights record against women, studying the Chinese system so that we can have actual good-faith conversations about its faults and merits, or learning to defend ourselves against future attacks on socialist nations that are built upon lies and slander.

At a time when Peng Shuai is asking us for privacy and respect, we need to be pushing for this for China too.

Eben Dombay Williams, is a member of the YCL’s Glasgow branch