Pierre Marshall reviews the latest reprint of ‘Third World War’, a storyline written by Pat Mills and Carlos Ezquerra which appeared in the British comic magazine, Crisis.

Oxford-based comics publisher 200AD recently reprinted the second book of ‘Third World War‘ – a story which ran in the magazine ‘Crisis‘ through the late 1980s/early 1990s. The magazine was characterised by an overtly political tone, part of a revival of mature themes in comics which was tragically misinterpreted by a mainstream United States audience as a ‘moody superheroes’ period. Crisis explained itself through its own dictionary definition:

A state of affairs in which decisive change, for better or worse is imminent. A time of acute difficulty or danger.

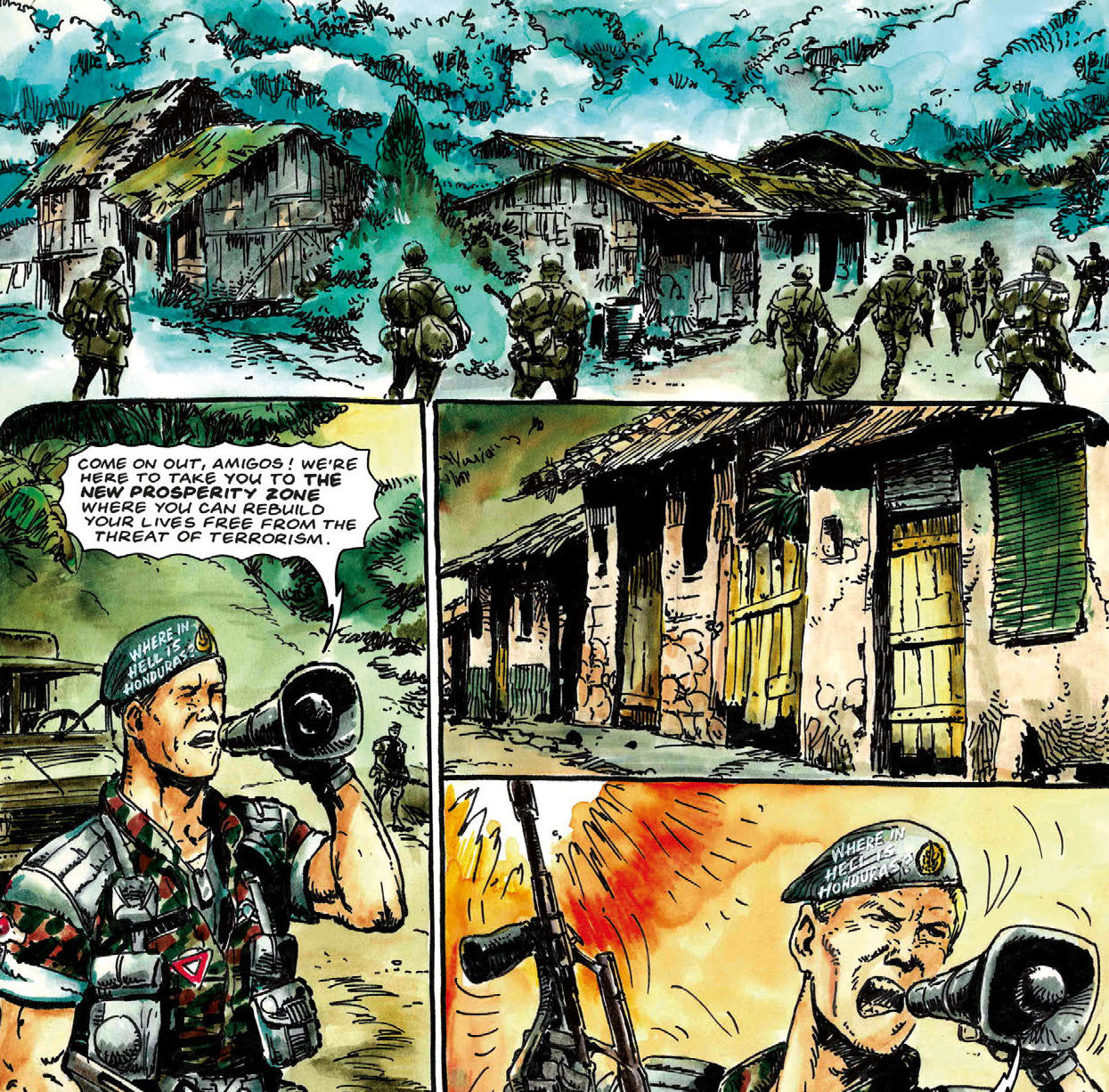

The first book of Third World War opens with a group of misfit humanitarians in an anonymous South American country. On their journey they experience all sorts of horrors committed in connection to a fictional fast-food company called ‘multi-foods’. This company features a dragon mascot, who crops up throughout the story with sinister messages in the form of advertising. The story often raises pretty harsh themes, such as the violent clearing of indigenous people from the land, and the actions of ‘death squads’ who kidnap women off the street. Overall the world painted by the comics matches the emancipatory imagery of neoliberalism with the harsh repression of the state and the multinational corporations. It draws a line between tasty burgers and children dying of malnutrition, the two things brought together in the unity of capitalist globalisation. Global Village / Global Pillage!

The writers point out in passing that Mein Kampf was a bestseller among the middle class in this country, the wealthy families privately considered Hitler a hero. That’s not far off the mark in its understanding of the support base for reactionary projects in South America. On a few occasions the comic is directly informed by reality, for example one of the side-stories is about a character who witnessed the death of a Jamaican child killed by poisoned rice. It was surprising to learn that this wasn’t a fictional event, there were real poisoning incidents in Jamaica around imported rice and flour in 1975 and 1976. Although there’s no firm proof, the poisoning was interpreted as an attempt by the CIA to destabilise the non-aligned Jamaican government; similar poisoned imports had also appeared in Cuba.

Another side-story features the character Superbarrio Gomez, a Mexican wrestler who dedicated himself to social justice, and a fascinating true story. Anecdotally, some of the panels with racist skinheads feature dialogue directly copied verbatim from a real-life encounter. One issue brings up Lawrence Budhoo’s resignation from the IMF, and the comic includes excepts from his resignation letter.

“Today I resigned from the staff of the International Monetary Fund after over 12 years, and after 1000 days of official fund work in the field, hawking your medicine and your bag of tricks to governments and to peoples in Latin America and the Caribbean and Africa. To me, resignation is a priceless liberation, for with it I have taken the first big step to that place where I may hope to wash my hands of what in my mind’s eye is the blood of millions of poor and starving peoples.”

These breaches of fiction ground the comic in an uncompromisingly bleak picture of Thatcher’s Britain, which is difficult to understand for those of us who were born long after 1990. I wonder what the series would have looked like if Crisis had continued publication into the early 2000s, as the two faces of neoliberalism were embodied in New Labour. The cynicism of Cool Britannia and the Iraq War.

Third World War is all the more significant as an object of history because it appears right at the turning point in the 1980s where across the world the forces of labour were on the back foot. In this historical landscape, which saw Communist Parties collapse across the world and anti-colonial governments turn to market reforms, class struggle was reframed through the eyes of NGOs as a story of the people against the multinational corporations. You can see how Crisis took up enthusiastically with this tendency, the inside cover of the magazine included contact details for Amnesty International, Greenpeace, Third World First, and others. Unfortunately the reprinted collections are missing all these editorial notes, which otherwise provide a valuable political context.

The second book takes place in Britain, broadly themed around a black defence group, with minor divergences around the personal relationships of Eve, one of the main characters. The main antagonists are a privatised police force which crosses over with corporate security, and along the way the story frames police violence in Britain alongside military occupation in Northern Ireland, or South Africa under apartheid. It’s all held together by the plot which has Eve return from South America only to find that the kind of conflict she saw abroad also exists at home. If Third World War deserves this criticism, it’s driven more by a set of loose themes than by a strong over-arching plot. The character of Paul was reinvented as ‘Finn’, a menacing eco-terrorist, eventually diving off into his own dedicated series which continued in 2000AD. Third World War itself struck out in various directions before slowing to a natural halt along with the end of Crisis magazine itself.

The story was also mired in the political confusion of the time, most visible later in the series when the counter-revolutionary movements of 1989 were cast in the hope for a more humane socialism. For example, issue #45 of Crisis included a special story retelling the events around Tienanmen Square in China in May 1989, naively reading it as a genuine workers uprising.

Throughout the series, Eve plays the role of a self-critical narrator, committed to the cause, yet always ready to point out the contradictions in her own actions and those around her. It’s partly through this critical dialogue that the most one-dimensional characters take on slightly more complex personalities. In ‘The Killing Yields’ Eve is caught up in a firefight with a rebel, which ends with her shooting her opponent; she never expresses remorse for the killing, but she does take a photo of the body to “show people what’s going on”.

Another place this shines through is in Eve’s encounter with a police officer much later on in the series. The policeman’s desire to punish Eve is interrogated at length by the writers, reflecting it through an obsession with colonial conquest and domination. It’s not at all comfortable reading, but it goes a long way to develop character motivation, as well as a sharp political point about the origins of racist police violence. All the way along you can almost see the writers contriving these situations in order to pick apart the assumptions of the reader.

Finally, this latest reprinting of Third World War is part of an overall project by Rebellion/2000AD to republish old classics under the ‘Treasury of British Comics’ imprint. I’m not sure how to feel about this, given how it’s motivated as much by a business strategy as a genuine desire for preservation. Still, the result is that Third World War got an unexpected chance to be read again by a new audience, in conditions where it probably would have faded away into obscurity. I don’t know if 2000AD intends to reprint the remainder of Third World War, honestly the later issues don’t stack up to the quality of the first book.

Anyone looking for original second-hand issues of Crisis magazine, some issues can be found at the Collectors Centre in the Harrison Arcade, Reading. Digital reprints of Third World War can be bought directly from 2000AD here:

Pierre Marshall, is a member of the YCL in Leicester