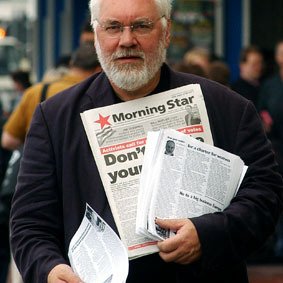

Nick Wright argues the people of the Irish Republic and their government have had a rude lesson in the politics of inter-imperialist rivalry. This article first appeared in the Morning Star.

George Osborne, the former Tory chancellor of the Exchequer, has downsized his portfolio career and gone to work for a boutique bank.

His parting shot as he vacated the editor’s desk at the Evening Standard was a reflection on the long decline of British imperialism centred on what he characterises as the errors and omissions of a ruling class to which by birth, education, wealth and high offices of state he is wedded.

In Osborne’s conspectus it was the policy failures of the Lord North, Britain’s premier at the time, that led to the loss of the North American colonies and similar missteps which weakened resistance to Irish home rule.

From this irredentist standpoint, Osborne segues effortlessly to voice the present-day angst felt by that section of British capital most wedded to the projection of present-day Anglo-US interests in Europe.

“By unleashing English nationalism,” he writes, “Brexit has made the future of the UK the central political issue of the coming decade.”

“Northern Ireland is already heading for the exit door. By remaining in the the EU single market, it is for all economic intents and purposes now slowly becoming part of a united Ireland.”

Osborne’s starting point is the strategic interests of finance capital in this new configuration.

In pricing in the return of the Northern Ireland statelet to an all-Ireland economic dimension, he gives his verdict on both Boris Johnson and the political incompetents who lead the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP).

Having written off Northern Ireland, Osborne turned to the prospects of a Scottish “independence” referendum with barbed advice to Johnson to hold firm and refuse such an abomination.

This, he argues, would constitute an existential threat to the union compared to which the reassertion of Irish territorial integrity and even eventual statehood doesn’t.

This leaves the various strands of unionism caught between the trade winds of economic realism which now blow their business base to the more accessible markets on their side of the new Irish border and an electoral arithmetic which puts Sinn Fein five points ahead of the DUP.

Sinn Fein bang on about a border poll, but an alliance almost as unholy as that which united King Billy and the Pope means that it is Johnson and Ursula von der Leyen who are the unlikely midwives of this new dispensation.

Pity poor Arlene Foster. Forced to share government office with Irish republicans who may soon supplant her with their own candidate as first minister, she has to share leadership of her party with people who believe that human existence owes its genesis to divine intervention just a few thousand years in the past.

Some of her ministers take it as an article of faith that the future of humanity, at least for those of us with souls unshriven, is substantially shorter and an awful lot warmer.

Foster’s party has cannibalised the unionist and loyalist vote at the price of narrowing its appeal and has now seen its utility for the British ruling class eroded to the point where the most powerful commercial, financial and business interests see it as, if not an obstacle, then perhaps an irrelevance.

Where last year — while Johnson’s Brexit bind compelled him to attend to her desires — Foster thought there would be no border poll in her lifetime, now she has perhaps a few months to reflect on how dispensable to the British ruling class are its colonial satraps and how little regard it pays to their distinctive interests.

The border in Ireland — imposed on the Irish by imperial power a century ago — circumscribed the largest possible land mass where a unionist majority could be guaranteed.

That it included the main centres of industrial production at the time both ensured it would be jealously guarded as a source of profit and a mechanism to divide the Irish nation against its common interests. That world has gone, blown away by the winds of capitalist globalisation.

Both sides in the negotiations around Britain’s exit from the EU saw this anomalous frontier as a bargaining opportunity.

When it became clear that the larger strategic interests of British capitalism in securing a compromise with the EU negotiators could not be secured without relocating the economic border down the Irish Sea, the befuddled DUP suddenly saw how little its parochial concerns mattered.

In a moment they understood just how Irish they are and how quickly their British identity is evaporating.

Under the Good Friday Agreement a border poll can be called only by the Westminster government.

For the biggest proportion of voters this side of the Irish Sea, the issue is a matter of indifference.

The “Don’t knows” have it by 39 per cent. But a solid 36 per cent are in favour of one and only 25 per cent opposed. The YouGov sampling taken last spring shows a majority in favour of a border poll in every category of Conservative, Labour and Liberal voters.

Perhaps more wounding to unionist pretensions is the finding that an absolute majority (54 per cent) are not bothered either way.

No less an authoritative voice of capitalist realism than Robert Shrimsley, chief political commentator of the Financial Times, wrote last month that Democratic Unionists are now Irish reunification’s secret weapon and argued that the DUP’s strategic judgements “have been among the most consistently witless in recent politics.”

Shrimsley is an engaging and perceptive commentator with a sharp eye for realpolitik.

Offering himself as a strategic adviser to Ulster unionism, he argues that the arc of history may bend towards reunification but it can be very long.

His prescription is for unionists to make the best of both worlds and embrace this new hybrid state in which the political frontier runs through green fields but the economic border floats on the waves.

The unspoken subtext is that — in the same way as Britain’s fractured ruling class has reached an accommodation with both the EU and itself — unionists should smell the coffee.

For the people of the North this already entails a reckoning with the interplay of forces well beyond their control while every manifestation of the British connection will become progressively redundant.

The people of the Irish Republic and their government have had a rude lesson in the politics of inter-imperialist rivalry.

The EU negotiators shamelessly flaunted the Irish tricolour and endlessly proclaimed the inviolability of the EU’s solidarity with the Irish people and state.

But at the first moment when its incompetence in securing adequate supplies of Covid-19 vaccine was exposed, it reimposed the border as a sanction on a British government which, for all its manifest failings, took advantage of the sovereign powers it regained with Brexit to lay in an early stock of vaccines.

To the serial incompetence of the DUP we can now add the maladroit manoeuvrings of the EU Commission as new measures of witlessness.

The divisions in the British ruling class — manifested over Brexit and now more or less reconciled — provided one opportunity for the Irish to recover their sovereignty as a nation united on its own territory.

For all the forces in Ireland that freighted the EU with the magical power to transform their subject status, the complete disregard for their interests displayed by the EU is a first step in a new understanding of the class nature of this neoliberal project.

The architecture of partition is disintegrating and the question now is: what kind of united Ireland?

Nick Wright