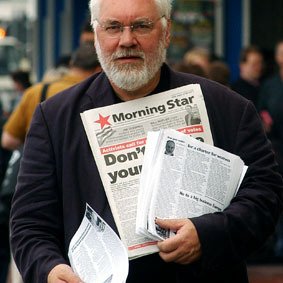

Nick Wright reports that for the Atlanticist lobby and its enthusiasts, the Cold War never really ended…. This article first appeared in the Morning Star.

Follow the Twitter feeds and various online channels of the Nato lobby, the Western Alliance enthusiasts and you enter an alternative universe in which the cold war never ended.

For these people — and the powerful forces whose megaphones they are — it never did end.

The recent death of George Shultz reminds us that only the flimsiest of permeable barriers separates out monopoly power, big business and government in the leading capitalist countries.

As adviser to both Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, Shultz was a key functionary in US imperialism’s power plays.

He went from the Chicago Business School to labour secretary under Nixon and from there to the Treasury where he was instrumental in ending the Bretton Woods agreement.

After heading up construction giant Bechtel — a major beneficiary of US defence spending — he became Reagan’s secretary of state.

He was central to the strategy to contain communism and box in the USSR, but it was his successor as secretary of state, James Baker, who gave Soviet leader Michael Gorbachov the assurance that Nato would expand “not one inch eastward.”

To argue that Gorbachov was duped presumes a level of political principle and alert statecraft on the part of the last Soviet leader that his subsequent pronouncements do little to support.

The fact is that he surrendered the treaty-given right of the USSR — to veto the incorporation of a unified Germany into Nato — on the assurances of “a parcel of rogues” including Margaret Thatcher, Francois Mitterrand, the brighter George Bush, Helmut Kohl and the CIA boss Robert Gates.

On his watch the security gains of the victorious war against fascism were thrown away.

Baker told Gorbachov’s foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, that in a post-cold war Europe Nato would no longer be belligerent — “less of a military organisation, much more of a political one, [that] would have no need for independent capability,” he cooed.

Today 13 eastern European states are members of a revived and reinforced Nato and British troops are not the only Western forces stationed on Russia’s western frontier.

Far from a zone of tranquillity, central and eastern Europe has become a patchwork of reactionary, racist and anti-semitic regimes where fascist forces are tolerated and in some states built into the political systems and security agencies.

That little remains of socialist property ownership in these former socialist countries is a given.

While Russia is still a substantial military power, its economy is largely privatised, much smaller and the former USSR is fragmented into a patchwork of nominally independent and sometimes antagonistic states that themselves are the playthings of foreign capital and in the corrupt compass of local cliques.

In this environment Nato is in the midst of a recalibration of its role that is partly pure public relations and partly strategic repositioning.

The rhetoric is strikingly hypocritical. Nato, which abandoned international legality and UN principles to wage war on the unified socialist Yugoslavian state, describes itself as “a unique community of values committed to the principles of individual liberty, democracy, human rights and the rule of law.”

Nato defines its three essential core tasks as collective defence, crisis management and co-operative security.

This it locates within a framework of what is coyly termed “transatlantic consultation” with a nod in the direction of “a continuous process of reform.”

Less prominent in its public posturing is Nato’s continuing commitment to its concept of civil resilience.

This it frames within a context of a continuing post-Soviet threat with Russia’s reassertion of its sovereignty over the Crimea linked to the new threat of Isis/Daesh terrorists and a new category of so-called “hybrid threats” including cyber attacks.

The new doctrine is made explicit: “based on the recognition that the strategic environment has changed, and that the resilience of civil structures, resources and services is the first line of defence for today’s modern societies.”

First line of defence? Not the nuclear deterrent against an always illusory pre-emptive strike? Not armoured divisions on the central German plain? Not even the electronic eavesdroppers of GCHQ?

Now the key battlegrounds are the suburban terraces of Croydon, the signal systems of a privatised railway, the pumping stations of the no less privatised water companies, the well-stocked shelves of Waitrose and the unfettered networks of Amazon and Google.

In this one sentence what was a supposedly military alliance grounded in a nuclear-armed mutual deterrence strategy and mutual territorial defence is transformed into a multilateral Atlanticist mechanism for intervention in and manipulation of what are nominally sovereign states.

Until Britain’s withdrawal from the EU’s political machinery, defence integration between Nato and EU structures was bundled into a joint defence mechanism first given substance by the 2002 Berlin Plus Agreement and the 2018 Joint Declaration.

None of this is particularly new. Nato has always been as much about buttressing internal security and “the continuity of government” as any other objective.

Obscured by its strategic deterrence rhetoric, Nato has, since its foundation in the post-war years, maintained a big effort in what it describes as its “important role in supporting and promoting civil preparedness among allies.”

Article 3 of Nato’s founding treaty requires all allies to “maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack” and this is defined as “supporting continuity of government and the provision of essential services in member states and civil support to the military.”

Behind these bland words there lies a long history of direct and criminal intervention in domestic politics.

During the nationwide French strike movement in 1947 which resulted in the exclusion of the French Communist Party from the liberation government, the CIA funded the Force Ouvriere split from the left-led Confederation Generale du Travail (CGT) and bankrolled the notorious Guerin clan of Marseille gangsters to murder CGT militants.

In 2006 the US State Department stated that accusations of US complicity in the political crimes of the Nato-organised Gladio network were examples of Soviet disinformation.

Gladio was the codename for the secret network of intelligence and military operatives nominally charged with preparing “stay-behind” resistance to a Soviet military attack.

In practice their main work was in subverting the labour movement and communist parties in Nato states and co-ordinating terror attacks with fascist and criminal gangs.

According to the official government inquiry, Switzerland’s Projekt-26 outfit was run in “close contact” with Britain’s MI6.

There is an extensive literature on Gladio which can be seen as the Murder Incorporated end of Nato’s resilience strategy.

The commander of the Italian Gladio operation, one General Serravalle, stated that “in the 1970s the members of the CPC [Co-ordination and Planning Committee] were the officers responsible for the secret structures of Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Italy.

“These representatives of the secret structures met every year in one of the capitals…

“At the stay-behind meetings representatives of the CIA were always present. They had no voting rights and were from the CIA headquarters of the capital in which the meeting took place … members of the US Forces Europe Command were present, also without voting rights.”

It is a bizarre notion that the Nato task group charged with terror and the subversion of bourgeois democracy conducted its affairs as if it were the committee of a pub scrabble team.

Despite the State Department’s protestation there is little attempt to deny this history but there is a renewed attempt to future-proof the internal security regimes of capitalist states that increasingly are prey to shocks like the 2008 financial crisis that arise from their essential capitalist character.

In the spring of 2018 Nato hosted a resilience conference in Norfolk, Virginia.

General Andre Lanata, Nato’s supreme allied commander [for] transformation, told participants that “each Nato country must be resilient in order to withstand shocks like critical infrastructure failure, military attack and natural disaster.”

He continued: “We serve as the Warfare Development Command, a command that prepares Nato for every eventuality and provides, by design, end-to-end coherence of the Nato military instrument; and resilience is a necessary component of that instrument.

“When a shocking event occurs, the response must be holistic, systematic and well prepared.”

Of the seven categories of challenge to the “resilience” of the civil authority and continuity of government all but one — the ability to deal with mass casualties — are more likely to result from mass action by working people, strike action or civil disobedience rather than any external intervention, natural or otherwise.

In most countries, Britain not excepted, continuity of government and critical government services has been threatened rarely by natural calamity and mostly by strike action and protest.

Civil communications systems and public transport are improbable targets for foreign agencies, but weakly resilient to industrial action while a strike of lorry drivers is more likely to interrupt supplies to the shelves of Lidl or Morrisons than even the most devious schemes of Shanghai cyber spooks.

It is undoubtedly true that the complex character of modern society does depend on secure communications networks and their smooth functioning requires a good measure of vigilance.

But in every developed capitalist country the best guarantee of the resilience to which Nato devotes its extensive cadre of military minds is not a domestic military or intelligence network but the willing consent of the millions of working people who make society work.

Compared with the immediate post-war world, the infrastructure of European societies is vastly more developed and integrated, and depends much more on the enormous number of highly skilled working people. Furthermore — as the pandemic has demonstrated — it can only function on the work of a vast number of essential service workers.

The real enough confrontations in which Russia and China are seen as barriers to the full spectrum dominance of Western capital consume enormous resources.

But little in Nato’s posture signifies a serious expectation of military invasion, although it is always alert to the possibility of changing the configuration of nuclear weapons even though these are nominally bound by treaty obligations.

On the contrary, for the mix of politicians, soldiers, spooks and think tank functionaries who make up this mad milieu, the enemy is within.

Nick Wright