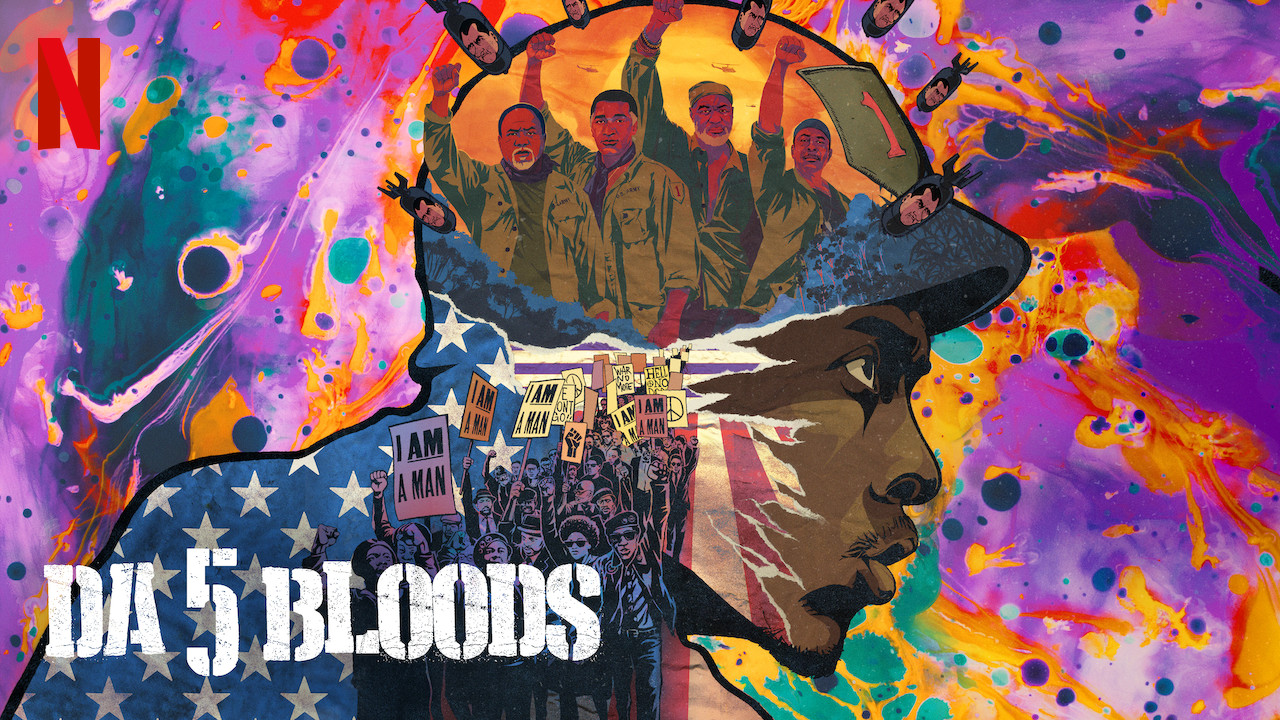

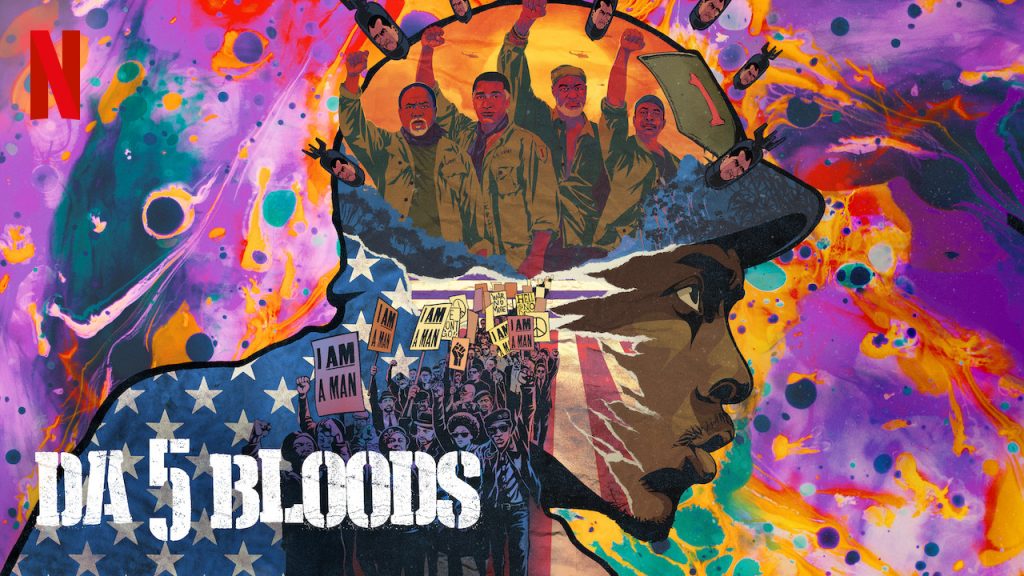

Dennis Broe reviews Spike Lee’s recent and celebrated film which attempts to tackle the experience of African-American US soldiers during and after the Vietnam War. This article first appeared on Culture Matters.

Spike Lee’s new film for Netflix, Da 5 Bloods, about the effects of the Vietnam War on African-American soldiers, opens spectacularly. A documentary sequence begins with Muhammed Ali detailing why he chooses not to fight: “My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother or some darker people… for big powerful America…..for what?..They never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me. They never robbed me of my nationality.”

Malcolm X explains the war as a continuation of a history of black exploitation in a country where “20 million Black people…fight all your wars and pick all your cotton and [you] never give them any recompense.” Over contrasting shots of the war and ’60s protests against it, comes the strains of Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues” where the singer plaintively pleads for an end to a system where while “bills pile up sky high” the response of a supremacist government is to “send that boy off to die.”

The film also ends strongly in the present summoning the Black Lives Matter protests, which echo again Marvin Gaye’s still prescient words about “trigger happy policing.” In between, unfortunately, things get a lot muddier.

In the fiction, the five soldiers return to Vietnam to recover a treasure trove of gold they had hidden during the war. Each of them, and especially Paul (Delroy Lindo) has been in some way damaged and traumatized by the war. Vietnam is now a prosperous country – a sex worker under the American regime is, under an independent Vietnam, a financial broker – but to return to it for these ex-soldiers is to re-invoke painful memories.

The film is aware of the idiocy of the Rambo myth, where Sylvester Stallone returns to fight the war and this time to win. Nevertheless it falls into a similar trap, as it recycles classical Hollywood images with the racist and imperialist residue of those images still intact. Lee’s film summons Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now with the Wagnerian “Flight of the Valkyries”, as the five travel upriver to find the gold. This is the least offensive of the references, because the original was cognizant of the lunacy of the war. Paul, wracked by guilt over what happened in battle, grows increasingly mad as they travel further upriver, suggesting that Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz and Coppola’s Brando character suffered from what would now be called PTSD – not innately mad, but driven mad by war.

Elsewhere though, the references are not so innocuous. Echoes of Treasure of Sierra Madre in the way the thirst for the gold divides the bloods give way to a direct quote in one scene which figures the Vietnamese as Sierra Madre’s scurrilous Mexicans, one of whom intones in a kind of Vietnamese/Hollywood/Spanish: “We don’t need no stinking official badges.”

The film cannot acknowledge that the Vietnam War was won by the Viet Cong, freedom fighters whose struggle against US imperialism is the same struggle that African-Americans are engaged in today in the inner cities of the United States. Thus, one character, who can’t stop refighting the war, is executed in a way that depicts the Vietnamese as bloodthirsty bandits. The only male Vietnamese character the bloods trust is a bounty hunter, whose parents fought for the US puppet government of South Vietnam. A flashback to the ’60s battlefield continues the “othering” of the Vietnamese by showing them only in outline, an approach used in Oliver Stone’s far better Platoon and which has been criticised.

Finally, the film, since it positions itself within the traditions of the War Film and the Western, complete with the bloods in campfire scene (surrounded by hostile Indians/Vietnamese?), must end in a battle. This one features the bloods and their European NGO allies against Jean Reno’s bloated Frenchman, and again the nearly faceless Vietnamese are simply enlisted behind him in a way that suggests nothing has changed in Vietnam since the French were driven out in 1954.

With heavy casualties the bloods win the battle and so in a way replay the Vietnam War. We’ve come both a long way and not very far at all from Rambo.

Dennis Broe

This article first appeared on Culture Matters.