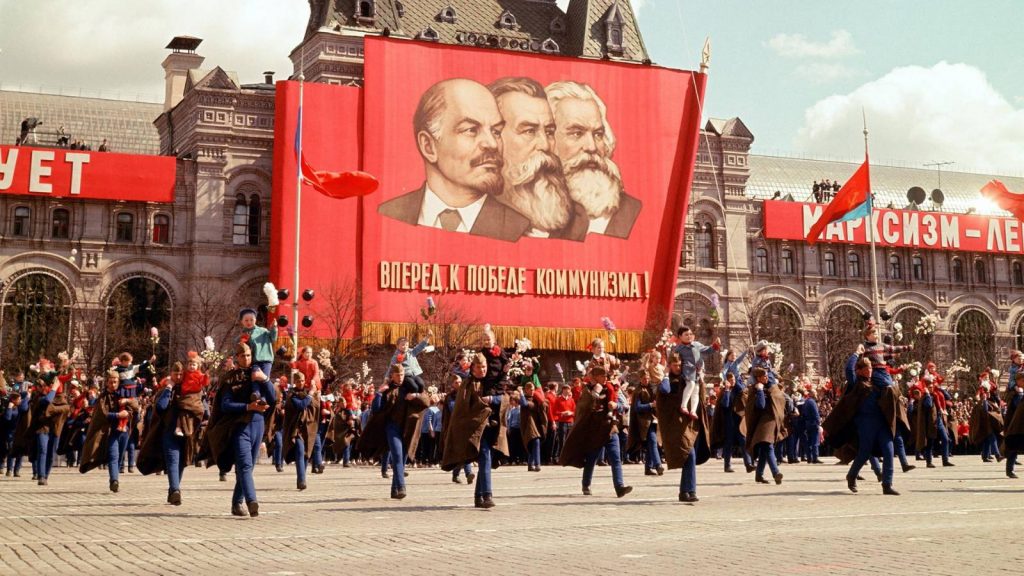

The origins of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) trace back to the 1917 October Revolution, when Russian workers and peasants, led by the Bolshevik Party, overthrew the bourgeois coalition government, stormed the Winter Palace, and transferred all power to the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, and Peasants’ Deputies in a largely “bloodless” revolution with minimal casualties.

The term “soviet” simply translates to “council,” working-class democratic structures which had become widespread throughout the country in the decade preceding the revolution. The network of elected soviets functioned as new municipal authorities, issuing decrees in the interests of working people. However, it was only after the 1917 October Revolution that these councils gained the complete authority to govern all questions related to the administration of the nation. Therefore, the basis of the Soviet economic system can be understood as the direct administration of the workers in all aspects of economic life where, in the words of Lenin, “every cook must learn to govern.”

Immediately after the October Revolution, imperialist powers conspired to destabilise the new republic through intervention and civil war. While the Don Cossacks had already initiated the civil war, from the outset, those rebelling against the Bolsheviks depended entirely on the assistance of the imperialist powers.

As World War I ended, the Entente powers—including Britain, the United States, France, Japan, Greece, Italy, and China—invaded Russia from all sides, supported by Tsarist generals and provisional politicians. The ensuing four-year war devastated the country and led many to question whether the revolution would survive. However, despite these challenges, the Bolsheviks emerged victorious, establishing the Soviet Union in 1922.

The USSR initially comprised four constituent republics: the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Transcaucasian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic (now Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia), and the White Russian Soviet Socialist Republic (now Belarus). In 1925, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic and the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic also joined.

From its earliest days, the Soviet Union organised itself on the basis of a planned economy. Here, profit ceases to be the main incentive of production. Instead, production takes place according to the real and growing needs of the people. Following the implementation of the new, socialist economy, Soviet citizens enjoyed unprecedented improvements in their quality of life.

In Tsarist Russia, living conditions were miserable. In the villages, families resided in mud huts, while in the towns, workers were cramped together in barracks, often three to a bed. In 1912, there were 24,500 cubbyhole flats in Moscow housing 325,000 people.

The Bolsheviks abolished the private ownership of land and issued an order allowing for the houses of the rich to be divided into flats. Between 1918 and 1928, half a million workers and their families from the most overcrowded areas of Moscow were relocated to better flats. Efforts were then directed towards constructing residential buildings. Between 1926 and 1939, 213 new towns and 1,323 new urban communities were built.

The Soviet Union was the first nation to implement universal and free healthcare, a system later copied by state capitalist nations like post-war Britain that were fearful of socialist revolutions of their own. This resulted in a surge in the availability of medical professionals, hospitals, and healthcare facilities to the Soviet people. The number of clinics rose from 1,230 in 1913 to 13,000 by 1940, while rural regions witnessed a fourfold increase in physicians and hospital beds. The quantity of hospitals in 1955 reached 24,428, five-and-a-half times greater than the 1913 amount. Infant mortality also declined rapidly, with a rate of 22.9 deaths per 1,000 births in 1971 as compared to 272 deaths per 1,000 births in 1913.

Relief was provided to disabled citizens and to families with multiple children; housing was constructed, and rents were limited to less than 5 percent of income; an intricate system of public transport, with low fares, was developed; a wide range of free cultural services were developed including vacations at cut rates or free of charge; and a widespread network of nurseries, schools, and libraries were built.

In the years before the revolution, the number of children attending school was around eight million (of whom only half received secondary education)—by 1934, the number of children attending schools had reached twenty-five million. Secondary education was also offered to adults free of charge at evening classes in every place of work. In turn, adult illiteracy rates decreased from over eighty percent in pre-revolutionary Russia to less than ten percent by 1934.

The Soviet Union was the first nation in history to introduce the legal eight-hour working day, which was reduced to six hours for dangerous professions. Equal pay for equal work was enforced regardless of sex, age, or nationality. Women received additional benefits, including four months of paid maternity leave. Working conditions were heavily regulated. The practice of children under fourteen being employed in industry was abolished. Workers were provided with two weeks’ paid vacation. Employers were obliged to provide free or low-cost housing, fuel, water, electric light, transportation, working clothing, dental and medical services and social security. Health and safety regulations were strictly enforced by labour inspectors, in turn reducing the number of accidents and occupational diseases.

Social security was a fundamental right offered to all Soviet citizens. Sick benefits ranged from fifty to ninety percent of regular wages. In the Soviet Union, an old-age pension scheme was introduced in Article 129 of the 1936 constitution. By 1938, it covered practically all workers. Men were entitled to pensions at sixty and women at fifty-five, much earlier compared to the Western world.

However, this steady growth encountered a huge disruption when Nazi Germany launched “Operation Barbarossa” in 1941, its brutal invasion of the Soviet Union. In response, Stalin called upon the Soviet army and people of the Soviet Union to stand as one. At the huge cost of 30 million Soviet lives, the invading forces were defeated, the occupied territories liberated, and, in a final triumph, the scourge of fascism destroyed on its own territory and socialist republics, the people’s democracies of Eastern Europe established in their stead. The defeat of Nazi Germany demonstrated not only the extraordinary courage of ordinary individuals who sacrificed their lives in the fight against fascism, but also the superiority of socialism over fascist barbarism.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the CPSU set about the monumental task of rebuilding a devastated nation, with 6 million homes, 98,000 farms, 32,000 factories, 82,000 schools, 6,000 hospitals, and thousands of miles of railways lying in ruins. More than half of all Soviet cities were gutted, and every third house in the countryside had been razed to the ground. Owing to the resilience and determination of the Soviet people backed by an incredibly efficient socialist system, the Soviet Union was able to make an extraordinary recovery. By 1950, the pre-war GDP levels had already been surpassed, and by the 1970s, the nation had grown into the world’s second largest economy. This era of growth was also marked by a series of groundbreaking scientific achievements: the launch of the first satellite into space in 1957, the journey of the first man in space in 1961 and first woman in 1963, and the establishment of the first space station in 1971. In less than a generation, the USSR had been transformed from a feudal peasant economy into a thriving socialist superpower at the cutting edge of scientific discovery.

Despite these achievements, the stability of the CPSU had slowly begun deteriorating, particularly after Stalin’s death in 1953. This event saw millions of Soviet citizens come out to show their grief—the largest demonstration of public mourning the Soviet Union has ever seen—and yet Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin’s successor, sought to distance himself from the Soviet Union’s achievements during the Stalin era and to secure his own leadership. In his infamous 1956 “secret speech”, he therefore presented sixty defamatory “revelations” against Stalin which were quickly circulated by the CIA throughout the world via outlets such as Voice of America. For decades, this speech was cited as a credible source by liberals and anti-communists throughout the world. However, its fraudulent nature has since been revealed through the examination of hundreds of primary sources and documents from the former Soviet archives. An objective analysis of the triumphs and failures of the Stalin period is only possible once anti-communist smears and disinformation has been discarded.

The Twentieth Congress of the CPSU which followed then promoted various distortions of Marxist-Leninist theory, particularly Khrushchev’s “three peaceful principles.” These included the theory that the strength of socialism throughout the world had opened the door to the peaceful transition to socialism through bourgeois parliaments, rather than revolution; and the potential for “peaceful coexistence” between imperialism and socialism and “peaceful competition” between two antagonistic economic systems, none of which stood up to the test of history.

Khrushchev’s anti-communist turn also had catastrophic repercussions for the world communist movement, not only precipitating the Sino-Soviet Split, but demoralising communist parties throughout the world and contributing to a loss of hundreds of thousands of members globally after record high memberships under Stalin. Khrushchev also inspired Mikhail Gorbachev’s disastrous “glasnost” and “perestroika” reforms of the 1980s, which undermined the CPSU’s leading role over society in favour of a liberalisation of the political and economic system. In 1991, this ultimately culminated in Boris Yeltsin’s coup, and the Soviet Union was dissolved despite nearly 78 percent of the populace voting to preserve it.

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping posed the question “Why did the Soviet Union collapse?” to the Communist Party of China. After investigation, the leading cause was identified as historical nihilism: “They repudiated their history, repudiated Lenin and Stalin. They succumbed to historical nihilism. This caused ideological confusion. The Party lost effectiveness at all levels. The army was no longer under Party leadership. In the end, the CPSU and the USSR fell apart. Let this be a lesson for us all.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a colossal increase in inflation alongside unemployment, homelessness, prostitution, suicide, infant mortality, and a range of other social ills, and from 1990 to 2010, recent estimates place the number of excess deaths in Russia at some 12 million people, all as a result of capitalist restoration. While under socialism, workers had enjoyed sick leave, maternity leave, and paid vacations, and had widespread access to health clinics, nurseries, and facilities for sports and culture, this all but completely faded away.

The position of women in society also began to regress. While Soviet Russia was the first major European nation to grant all women the right to vote, and the Bolshevik Party was the first to include a woman in a governing cabinet, after the collapse of the Soviet Union there was a drastic reduction in female political representation and employment. Maternity and prenatal care were cut back severely, affordable daycare centres were closed, and incidents of domestic violence surged with the annual number of women murdered almost tripling in Russia in the first three years after the Soviet Union’s collapse.

While bourgeois economists often point to the collapse of the Soviet Union as “proof” of the inherent shortcomings of socialism, and Trotskyists of socialism in one country, the Soviet economic model undeniably brought with it unprecedented improvements in the quality of life of its citizens, even as it rebuilt from the devastating losses of two world wars. And although its collapse was a significant defeat for the international working class, socialism is still carried forward by socialist countries and Marxist-Leninist parties all over the world.

Further Reading:

Khrushchev Lied, G. Furr

Speech to the 20th Congress of the C.P.S.U., N. Khrushchev

Stalin: History and Critique of a Black Legend, D. Losurdo

The Tax in Kind, V. Lenin

Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR, J. Stalin

History of the CPSU(B): Short Course, J. Stalin

Discussion Questions:

- What were the soviets and what purpose did they serve in the revolution? What would be the equivalent in Britain?

- The Russian Revolution was achieved by an armed uprising but with minimal casualties. Is revolutionary violence a bad thing? How should we approach violence as communists?

- What impact did the Bolshevik Revolution have on Britain?

- What impact did Khrushchev have on socialism in the Soviet Union and globally?

- Mao Zedong famously described Stalin as “30% bourgeois, 70% Marxist,” with a similar level of nuance later used to describe Mao himself. Why is it important to support figures like Stalin and Mao, despite their mistakes and the anti-communist propaganda against them?