Defined simply, racism is an ideology that attributes certain characteristics or behaviours to groups of people and deems them to be either superior or inferior based on these determinations. Although commonly associated with skin colour, racism is by no means dependent on this. For example, in 19th century Britain, the Irish population was subject to racism despite having the same skin colour as the British natives.

“Scientific” theories of racial difference first came to the forefront during the Enlightenment when philosophers and anthropologists began dividing humanity into “superior” and “inferior” races. They deemed the former to be of a biologically higher stock and destined to rule, while degrading the latter as “subhuman” and justifying the most brutal methods of colonisation and slavery. Today, the notion that humans belong to races with different intellectual and physical abilities is scientifically discredited. However, racism has not disappeared; instead, it has been forced to change its form, shifting its focus from biological differences to cultural differences and being used to justify political and military intervention, often under the pretext of bringing “superior” Western values to developing countries.

Many progressives have committed themselves to the struggle against racism which, while commendable, means very little without a comprehensive and scientific analysis of racism itself: why it exists and how to eliminate it. To this end, there are numerous competing theories on racism’s origins. Some attribute racism to an “instinct of human nature”, suggesting that we are naturally driven to sort people into racial categories and to recognise the superiority of those who resemble us. Others attribute racism to European civilisation and tradition, arguing that it has been present throughout all epochs of European history and has, therefore, become deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness of European society.

On the other hand, Marxists understand that racism is not inherent to human nature or any particular nationality, but, like all ideologies, derives from the economic base of society. While Marx is often criticised as having neglected racism, he did, in fact, describe the processes that gave rise to it in Capital, writing, “The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement, and entombment in mines of the indigenous population of the continent, the beginnings of the conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve for the commercial hunting of black skins are all things that characterise the dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

To Marxists, therefore, racism is a development serving to justify the brutal mistreatment of colonial subjects and slaves during an epoch that professed “liberty, equality, and fraternity”. In this respect, colonisation, slavery, and class society have always been intertwined. As Fred Hampton explains, “We [the Black Panther Party] never negated the fact that there was racism in America, but we said that… capitalism comes first and next is racism. That when they brought slaves over here, it was to take money. So first the idea came that we want to make money, then the slaves came in order to make that money. That means that… through historical fact, racism had to come from capitalism. It had to be capitalism first and racism was a by-product of that.”

Slavery and colonisation generated the huge amounts of capital necessary to fuel the Industrial Revolution first in Britain, and then across Europe and North America. To sustain this relationship, planters and colonisers promoted racial ideologies that legitimised their exploitation of the colonies and reinforced the subhuman status of the colonised peoples. We can see parallel forces at work today, with anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism in Britain stemming directly from US imperialist interests in the Middle East, such as the Iraq War. Liberal anti-racism must therefore be exposed for the hypocrisy it is, and all racism must be tied to its basis in capitalism and imperialism.

Racism not only served to fuel the exploitation of the colonised countries, however, but also to keep workers divided within the imperialist countries. Marx commented on this phenomenon in his 1870 letter to his friends Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt, stating that “Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker, he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the ‘poor whites’ to the Negroes in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.”

Even today, capitalists are attracted to immigrant labour due to the economic advantages it offers. By fostering competition among the working class for jobs, housing, credit, and so forth, capitalists are able to sow division along racial lines and undermine collective action. Furthermore, immigrants are drawn upon as a source of cheap labour and, due to their desperate circumstances, often find themselves unable to refuse employment in poorly sanitised and dangerous jobs beyond the reach of trade unions. This source of cheap labour is also made more readily available through imperialism and war.

Today, immigrants are often scapegoated as complicit in worker exploitation and the deprivation of working-class communities, despite the fact that both mass migration and worker exploitation have the same roots in capitalism and imperialism. These provide a steady stream of migrants seeking to improve their economic situation and a steady stream of refugees fleeing from imperialist wars. If we want workers to understand this, it is important for communists to provide our own answers to the legitimate struggles of working-class people in their own communities, partly through education and propaganda, but mainly through on-the-ground campaigning. It is important to show through our actions that only communists have a real answer to working-class deprivation, as resorting to moral condemnation or liberal-versus-conservative culture wars about a preference for “open” or “closed” borders can only exacerbate existing divisions.

In recent decades, racist ideology has been repurposed to justify the preservation of a US-led unipolar world order. Periphery nations are depicted as “despotic” and in need of saving by the West. Therefore, while slavery and direct colonial rule have largely disappeared, racist ideology continues to be used to legitimise the oppression of the Global South.

Racism, then, helps to maintain the functioning of capitalism and imperialism. It is thus in the interests of the capitalist class. But what about the workers? Some leftists argue that white workers benefit from racism, claiming that the super-profits exploited from the Global South are used to pay the higher wages of white workers. Although it is crucial to recognise the unique ways in which workers in the Global South are exploited by imperialist enterprises, this does not mean that white workers benefit from racism. Fundamentally, by dividing the working class, racism detrimentally affects all workers, regardless of race or nationality, by weakening class struggle, undermining the workers’ movement, and therefore by strengthening the position of the capitalist class and perpetuating exploitation.

As racism negatively affects all workers, we all share an interest in struggling against it. However, there are many different perspectives on how this should be done. Black nationalists, like Malcolm X was for most of his life, support the formation of specifically black or minority movements that exclude white anti-racists and reject the importance of class struggle and class unity. On the other hand, postmodernists often advance “privilege theory”, which holds that racism is best challenged by individual workers engaging in acts of moral condemnation amongst each other, and by challenging their own levels of “privilege” to risk becoming inadvertent oppressors.

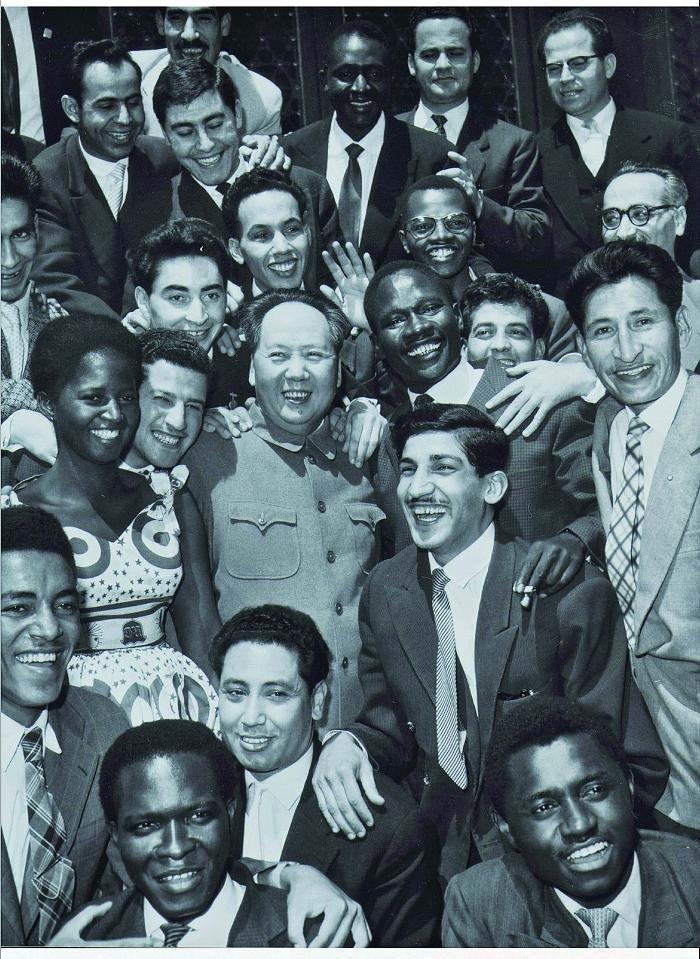

As Marxist-Leninists, we are unique in that we understand that racism can only be truly overthrown alongside the capitalist system, and that this can only be achieved through a socialist revolution composed of all races and nationalities united together against one common enemy: the bourgeoisie. We are not anti-racist merely because this is “morally right”, but because racial divisions hinder the working-class movement from achieving unity and making strides towards socialism.

Further Reading:

It’s a Class Struggle, Godamnit!, F. Hampton

Marx to Sigfrid Meyer and August Vogt in New York, K. Marx

Ireland and the Irish Question, K. Marx and F. Engels

Discussion Questions:

- Are moral arguments effective against racist views? Why/why not?

- Why is it not possible to fight racism without fighting capitalism and imperialism?

- Why don’t communists argue for “open borders” or “closed borders”? What would happen in a socialist society with these policies?

- Have you noticed ideas like “privilege theory” circulating in the workers’ movement? What problems do ideas like this cause?

- Imagine that a fascist organisation is recruiting from a working-class community by directing hatred at refugees in a local hotel. How could communists effectively defuse this situation? What would make the situation worse?