“The exploiting classes need political rule to maintain exploitation, i.e., in the selfish interests of an insignificant minority against the vast majority of all people. The exploited classes need political rule in order to completely abolish all exploitation, i.e., in the interests of the vast majority of the people, and against the insignificant minority consisting of the modern slave-owners – the landowners and capitalists.”

― Vladimir Lenin, State and Revolution

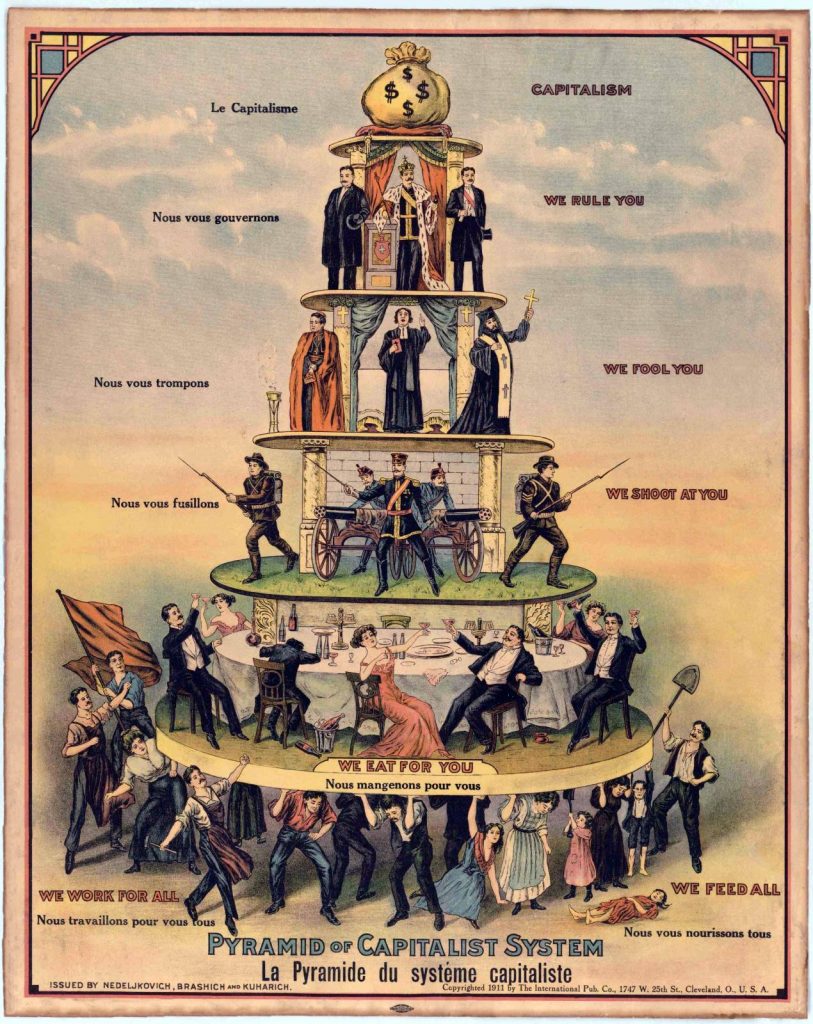

Bourgeois ideologists usually accept that we live in a class society, but often distort our understanding of class by referring to different factors such as income, cultural interests, regional accent, or sector of employment. Although class may have an impact on all of these factors, and these different factors may also impact an individual’s level of class consciousness (their awareness of belonging to a specific class and of their specific class interests), Marxist-Leninists have a very specific understanding of class which is different from the liberal academics.

Lenin described class as: “large groups of people differing from each other by the place they occupy in a historically determined system of social production, by their relation (in most cases fixed and formulated in law) to the means of production, by their role in the social organisation of labour, and, consequently, by the dimensions of the share of social wealth of which they dispose and the mode of acquiring it.”

The principal (but not only) defining factor of a class is therefore its relationship to the means of production, which is different depending on their position within the wider mode of production and how the economy is organised.

In early capitalism, the industrialisation of society and the separation of the peasantry from the land led to an increase of proletarian wage labourers working under capitalist business owners in the towns and cities. These existed alongside other “middle” classes, such as self-employed small business owners (the petty-bourgeoisie) and handicraftsmen.

Today, the principal contradiction is still between the proletariat or working class, which does not own the means of production and wants higher wages and lower profits, and the bourgeoisie or capitalist class, which does own the means of production and wants lower wages and higher profits. However, arguing that everyone who works or that all employees of a company have the same class interests quickly becomes nonsensical. The CEO of Coca Cola clearly has very different class interests to a labourer in one of their warehouses, despite the fact that both are employed to do a job on a salary or wage and rely on this for the majority of their income. The answer to this lies in the fact that all classes can be broken down further into different sub-classes or strata, which may have different or even opposing class interests. Mao, for example, broke the peasantry down into its small, medium, and large strata and assessed the interests of each of these different groups individually. Both the working class and capitalist class can also be broken down in this way.

The Working Class

British Marxists have been forced to grapple with the fact that the most recent stage of imperialism has fundamentally transformed the class structure of our society. For one thing, Britain has moved from being an exporter of commodities and manufactured goods to a service economy, with the large factory floors of industrial Britain as observed by Marx and Engels having largely moved to nations in the Global South to be replaced by smaller businesses, offices, as well as a vast, unproductive finance and banking sector.

Marx developed upon the ideas of Adam Smith to separate members of the proletariat into productive and unproductive workers, where productive workers were generally understood to be those workers who create value through their labour in the form of marketable commodities, after which a small amount is returned to them in the form of a wage, while the surplus value is appropriated by a capitalist. Clear examples of productive workers include miners and manufacturers, although Marx also considered transport workers productive in that they added to the value of a commodity by making it available across great distances.

Productive workers must always occupy the base of any mode of production, since the rest of society could not function without them. The goods they produce and the surplus value from their labour is used to support all the unproductive labourers and other classes above them, making productive workers the most revolutionary stratum of the working class which should form the core of any Communist Party. In Britain, the number of productive workers peaked in 1960 and has been in decline ever since the onset of neoliberalism.

On the other hand, unproductive workers are paid out of the surplus value created by productive workers while creating no additional value themselves, with common examples including shop assistants, waiters, and domestic servants. Employees in these sectors are still “working class” and society is often richer for their contributions, but it would not come to a standstill if these jobs didn’t exist.

Unproductive workers can certainly experience significant exploitation and precarity, but greater worker isolation in less productive employment can also make organising more difficult and strike action less effective, making this an important distinction in the development of revolutionary strategy. The reserve army of labour (unemployed workers) is another unproductive class stratum which is maintained by the capitalists in order to increase competition among the working class and drive down wages. The expansion of both of these strata has led to demands for reindustrialisation of the economy among some sections of the workers’ movement, and indeed, some sections of the capitalist class. This would grow what has typically been seen as the core of the revolutionary communist movement.

The progression to state-monopoly capitalism after WWII also led to a huge increase in the number of state employees in Britain. Although the subsequent neoliberal transformation away from a state capitalist economy has shrunk the size of the state sector, a large bureaucracy of state employees and civil servants still represents a significant proportion of the population, and is paid out of taxes on their fellow workers, rather than any value they actually produce. Many workers are also middle-managers, paid slightly higher amounts to keep the lower strata of workers under control, while many mental labourers, intellectuals, and professionals like students, teachers, and lawyers are paid to study and promote bourgeois ideologies or enforce bourgeois laws. Different combinations of these higher strata have been categorised in various different ways, including as an intelligentsia, as a “new” petty bourgeoisie, and as a professional-managerial class, although the lines between mental and manual workers have become increasingly blurred as the conditions of mental workers have deteriorated.

For example, although educational institutions like schools and universities used to be the exclusive domain of the upper classes (and to an extent still are, which affects class consciousness within them), a much larger section of the working population has now been admitted into education to provide them with the knowledge and skills to manage a more advanced form of capitalist economy. When Marxists talk about unity between people who work “by hand or by brain”, these are the class strata they are referring to.

In the early 20th Century, Lenin also described a class stratum which had emerged in imperialist countries like Britain as a result of the super-exploitation of workers abroad. Lenin called this the “labour aristocracy,” a higher fraction of the working class within the imperialist countries, particularly represented among the skilled “craft” trade unions, which was bribed by the capitalists with the profits of imperialism in order to divide the workers and stave off socialist revolution. This stratum and others among the upper working classes betray the mass of the workers by opposing militancy and urging conciliation with the capitalists, rather than effective use of the workers’ most reliable weapons: strike action and strength of numbers. They also diffuse militancy by channelling workers into ineffective forms of resistance in which the capitalist class has an overwhelming advantage, including lobbying, legal battles, and parliamentary elections.

Although craft trade unions have largely disappeared from Britain, replaced with the general trade unions of today, we can still see workers who receive more than the value of their labour in the form of abnormally high wages or salaries. Since these workers gain the full value of their labour, plus an additional amount, they must necessarily be receiving a share of the surplus value of their fellow workers, either at home or abroad. Different factions of these middle strata are represented by “middle-class” political parties like the Green and Labour Parties, and have come to dominate the mainstream “left” for some time now, particularly in areas such as the environmental movement, the trade union movement, and various forms of identity struggles.

This has created fertile ground for counter-revolutionary tendencies, such as reformism, and an individualistic culture and politics which the most revolutionary strata of the workers often find divisive. Lenin described the various “petty-bourgeois” ideologies which emerge among the working classes as the product of the constant collapse of the “middle” classes into the ranks of the proletariat. Without a concerted ideological struggle, these ideologies can have a divisive impact on the workers’ movement and set back revolution. It is the responsibility of communists to draw workers out of the influence of class traitors and other reactionary forces, and into militant struggle.

The housing movement also includes different classes and class struggles, although these distinctions may be more complicated than at first glance. For example, whether or not you own a home or rent it out does not necessarily change the fact that you need to work for the majority of your income, making you a member of the working class regardless, although there may be clear conflicting interests between workers who want higher or lower rents, for example. A tenant who moves out of their family home for study or work and so rents on a temporary basis, but can expect to inherit property later, is also different from a social or private tenant who would be made immediately homeless upon eviction. Likewise, a small landlord who rents out a second property to friends or family or who is self-employed and so keeps a second property as security for their retirement engages in far less exploitation than a large landlord with tens, hundreds, or thousands of rental properties in their portfolio.

The divisions between mental and manual, and productive and unproductive labour have caused contention among certain Marxist circles, but whether different fractions are understood as separate “middle” classes or simply different strata of the workers, the goal of class unity alongside an awareness of class differences and the need for a party led by the most revolutionary strata of the working class should be enough to guide any communist political strategy.

As an example, although students often experience downward mobility and precarious circumstances which can lead to socialist sympathies, their position in the class structure does not give them access to the levers of production or the ability to take strike action. Universities are also isolated from wider working-class communities and serve the capitalist class by propagating bourgeois ideologies, meaning they often become breeding grounds for liberal and individualistic cultures which can hamper effective struggle. From this, we can accept that students are generally not the most revolutionary section of the working class and therefore should not constitute the core of a revolutionary party, without neglecting the importance of promoting class unity and helping students to make more effective contributions to the revolutionary struggle on behalf of the wider proletariat.

Finally, Marx and Engels referred to a largely criminal underclass often exploited by the forces of reaction, referred to as the lumpenproletariat. Despite the fact that this group experiences a great amount of suffering, greater suffering does not automatically translate into revolutionary potential, and there is little class solidarity to be expected between workers and those criminal elements who prey on their communities. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels therefore write that the “lumpenproletariat is passive decaying matter of the lowest layers of the old society, is here and there thrust into the [progressive] movement by a proletarian revolution; [however,] in accordance with its whole way of life, it is more likely to sell out to reactionary intrigues.”

These divisions among the working class may make organising and unity more difficult, but we should take heart from the fact that the capitalist class has its own divisions which can be taken advantage of.

The Capitalist Class

Alongside the labour aristocracy in the imperialist countries, imperialism has also created a parallel traitor class in the colonised countries, known as the comprador bourgeoisie. This is a native capitalist class which is bribed by imperialists to maintain the imperialist relationship in exchange for a share of the profits. This is different to the national bourgeoisie, a capitalist class which is interested in opposing the imperialists and which can be convinced to side with the workers on a temporary basis, although their main objective is only to secure profits for themselves.

In Ireland, for example, there is a comprador capitalist class which supports British occupation, represented by unionist political parties such as the DUP, as well as a comprador class in the “free” Ireland, represented by political parties like Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, which seeks to replace one set of foreign imperialists with another through accelerating the predation of US monopolies like Apple through favourable tax rates. Meanwhile, any national capitalist class which can be convinced to oppose imperialism only does so in order to facilitate the development of a national form of capitalism.

Mao Zedong understood that, despite its untrustworthy nature, the national bourgeoisie represented a progressive class in the battle against imperialism. The Chinese flag has four smaller stars representing the four main classes in China involved in the alliance against imperialism: the national bourgeoisie, the petty bourgeoisie, the proletariat, and the peasantry. The national bourgeoisie in mainland China is a different class compared with the comprador bourgeoisie currently occupying Taiwan with the backing of the United States.

In the present era of imperialism, differentiating between national and comprador capitalists becomes exceptionally important if we are to correctly understand the new balance of class forces in the world that is attempting to build unity against US-led imperialism. This not only includes socialist countries, but also colonial and formally independent capitalist countries, many of which are still oppressed by more indirect, “neocolonial” forms of oppression.

By exploiting the differences between national and comprador capitalists, as well as the more traditional merchant and industrial capitalists and the finance and monopoly capitalists which have come to dominate in the era of imperialism, it is possible to split the ranks of the bourgeoisie and unite the workers against them.

Successful revolutionary movements in Russia and China were only possible after a surgical analysis of the class structure in their specific situations, including identifying both antagonistic and non-antagonistic classes and class strata based on their different needs and interests and how they interacted. Both Lenin and Mao wrote extensively on this subject, and the British labour movement is sorely lacking in an authoritative class analysis of British capitalism using contemporary statistics, which will be necessary if we are ever to guide the workers towards a revolutionary situation.

As Mao said, “Who are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution. The basic reason why all previous revolutionary struggles in China achieved so little was their failure to unite with real friends in order to attack real enemies… To distinguish real friends from real enemies, we must make a general analysis of the economic status of the various classes in Chinese society and of their respective attitudes towards the revolution.”

Further Reading:

The Housing Question, F. Engels

The Principles of Communism, F. Engels

A Nation of Shopkeepers: The Unstoppable Rise of the Petty Bourgeoisie, D. Evans

A Great Beginning, V. Lenin

Karl Marx, V. Lenin

Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society, Mao Zedong

Discussion Questions:

- Choose a political party, union, or other left-wing organisation. Which class(es) are represented and how does this affect its culture or how it operates?

- What are the challenges of building class unity in the era of imperialism? How should our revolutionary strategy change?

- What concrete steps can we take to ensure that the core of the communist party is represented by the most revolutionary sections of the working class?

- What class or class stratum do you belong to? What classes are represented in your community, workplace, or other organisation?

- How can we apply a class analysis to the types of campaigns we support or the types of events we participate in?