“Just as man is governed, in religion, by the products of his own brain, so, in capitalist production, he is governed by the products of his own hand.”

― Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1

Every material thing that can satisfy a human want or need has something called a “use-value”. The use-value of bread, for example, lies in its ability to provide us with nourishment; the use-value of glass is its capacity to satisfy our desire for natural light; and the use-value of books is that they stimulate our minds either intellectually or creatively. Marx made clear that the nature of these needs need not concern us, stating that “The nature of these needs is irrelevant, e.g., whether their origin is in the stomach or in the fancy.” In primitive, pre-class societies, human labour is directed towards the production of use-values, meaning that products are created for consumption.

As society develops beyond its primitive stages and a division of labour emerges, there comes a point where communities can start producing goods not solely for direct consumption, but also for exchange. For example, a community focused on wheat production would have no need to trade with another, similar community, as they both create the same product. However, if certain communities shift their focus to the production of different goods, the wheat-producing communities will now have an incentive to trade. Under these conditions, the goods that are produced for exchange have another value besides their use-value: an exchange value, and it is this value which transforms these products into commodities.

As Lenin explained, “A commodity is, in the first place, a thing that satisfies a human want; in the second place, it is a thing that can be exchanged for another thing. The utility of a thing makes its use-value. Exchange-value (or, simply, value), is first of all the ratio, the proportion, in which a certain number of use-values of one kind can be exchanged for a certain number of use-values of another kind.” Although production for exchange existed on a small scale under previous modes of production, capitalism is unique in that production for exchange is overwhelmingly dominant. Most products are now produced for profit, not for direct consumption to meet the needs of the people.

Commodity production did not suddenly burst onto the stage one day fully formed, but developed slowly over time. It was only as the means of production—the machinery, land, and materials necessary to produce commodities—became concentrated in the hands of a few individuals, and as independent artisans and peasants became ruined and transformed into wage workers, that simple commodity production developed into fully-fledged capitalist production. Under these conditions, use-values cease to be the driving force behind production; instead, exchange-value takes precedence, with the capitalists destroying the products that, for whatever reason, cannot be exchanged on the market for a price. It is a basic law of capitalist society that its profit-driven economy will tend towards the production of more commodities than the people can afford, leading to periodic crises of overproduction, known colloquially as cycles of boom and bust, including all of the other crises of unemployment, poverty, ruin, and civil unrest which inevitably follow.

We have established that capitalist society is primarily concerned with the production of exchange values rather than use-values. However, this still leaves the question of what determines the exchange value of a commodity unanswered. For this, Marx developed upon Adam Smith’s Labour Theory of Value, which states that all commodities share a common property in that they are products of human labour, and that it is this property that determines their value. Expressed differently, the exchange value of a commodity is determined by the average quantity of labour necessary to produce it. This includes what labour has been absorbed into a commodity through the wear and tear of machinery (also produced through labour).

Mankind universally shares the ability to learn and develop a variety of skills. However, under capitalism, this potential is only partially realised due to inequality in opportunity and education. In a socialist society, the full development of various skills is, for the first time, made possible. As Marx described it, communism “makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.”

Nevertheless, all individuals, skilled and unskilled, possess different capacities for labour. This presents us with an issue: if the exchange value of a commodity is to be based solely on the labour expended by an individual, the commodity produced more slowly by a weak, lazy, or incompetent worker would be of a higher value than the same commodity produced more quickly by a strong, hardworking, or competent worker. The exchange value of a commodity, therefore, is not determined by the quantity of labour expended by each individual producer, but by the average quantity of labour that is socially necessary to produce it under normal conditions across the whole of society.

This theory applies not only to commodities sold by the capitalist, but also to the only commodity available to the labourer to sell, their own labour power, which is sold to the capitalist on the market in return for wages. Like all other commodities, the value of labour power is determined by the quantity of labour that is socially necessary to produce it, namely, the labour expended over a lifetime in training a worker over and above the average.

Therefore, the labour-power of skilled workers has a greater value, while the labour-power of unskilled workers has a lesser value. Nevertheless, the additional income that skilled labourers receive will be considerably less than that of professionals in fields such as law enforcement, business management, investment, and banking, who are often paid disproportionately high wages and receive huge bonuses in exchange for their class loyalty, regardless of the value (if any) they actually produce. That said, there is an important distinction between skilled labour and unskilled labour which Marxists must understand in order to comprehend capitalism fully.

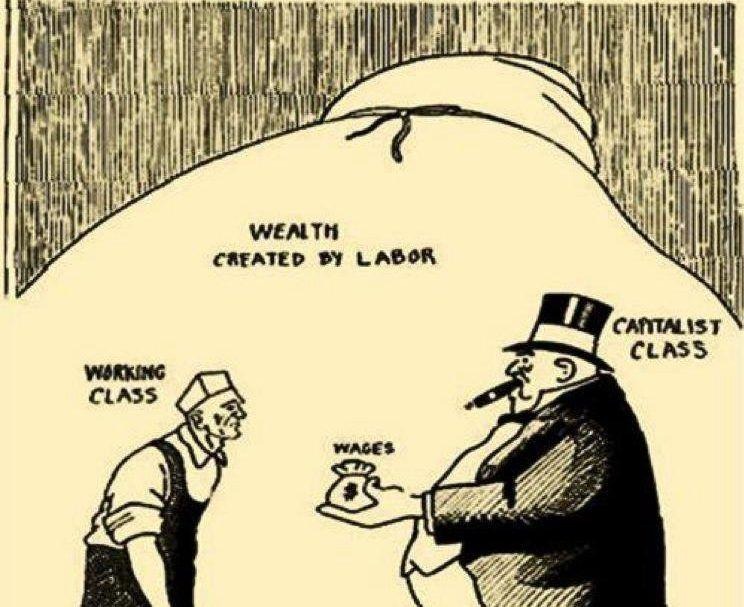

Besides use-value and exchange value, Marx also spoke of another value: surplus value. Put simply, surplus value is that portion of the value created by workers that exceeds the value that they receive in wages. This means, during part of their working day, they create value equivalent to their wages, while in the remaining part of the day, they produce surplus value which can be understood simply as unpaid labour. But how is an employer able to appropriate the surplus produced by a worker?

In primitive society, when production was limited to what was necessary for subsistence, this appropriation was impossible because everyone had to work to meet the needs of the tribe. As humankind developed more sophisticated methods of production, however, it became possible to produce a surplus over and above what was necessary for immediate consumption. The strongest tribes then began appropriating this surplus by enslaving those taken captive in wars, forcing them to work, and freeing themselves from the burden of labour—the beginnings of class society.

Throughout history, the ruling class has assumed various forms—master, lord, capitalist, and so forth—while the exploited members of society became the working class—the slaves, serfs, proletarians, and so on.

Under capitalism, the appropriation of the “surplus product” of the working class is concealed by money—the monetary form. As Marx explained, “The Roman slave was held by fetters: the wage labourer is bound to his owner by invisible threads. The appearance of independence is kept up by means of a constant change of employers, and by the fictio juris of a contract.” Therefore, while it might appear that workers are fully compensated for their labour under capitalism through wages, these wages will always be lower than the total value produced by the workers for profits to be extracted. All wage labour is therefore a form of exploitation, and our goal cannot just be to improve the conditions of the wage labourer, but to abolish this system of exploitation entirely.

Let’s look at an example to summarise what we’ve learned so far: A group of wage labourers, or proletarians, are employed in a factory producing mobile phones. The phone is a commodity whose use value is that it can be used to make phone calls, while its exchange value—what it can be exchanged for in terms of other commodities—is determined by the average amount of labour required to make it (socially necessary labour time), as well as the labour used to make the tools and machinery used in its production. Under capitalism, it is the exchange value which is most important. The worker cannot produce their own phones because they do not own the means of production (the tools, materials, machinery, energy supply, etc.)—these are owned by the capitalist—so the worker is forced to sell their labour power to the capitalist for a wage and give up any entitlement to the products of that labour. If a worker produces a hundred phones a day, but only receives compensation for one, then the surplus value stolen by the capitalist lies in the other ninety-nine which will be sold on the market. The worker has essentially produced the other ninety-nine phones for free. This is the essence of capitalist exploitation.

Finally, the labour of the working class does not merely create the means of subsistence for its own class, but for society as a whole. For the capitalist, income is derived from entrepreneurial profits; for the landowner, it comes in the form of rent; and for all the superfluous state employees, their salaries are levied by taxes on the working class, meaning that these ruling class elements all live parasitically on the labour and surplus value of the workers. Part of the surplus value is, however, reinvested by capitalists to generate an ever-greater quantity of surplus value. They expand their enterprises, hire more workers, install better machinery, and continually grow their capital. This is the essence of capital: value that produces surplus value, or self-expanding value.

Further Reading:

Capital Vol. I, K. Marx

Theories of Surplus Value, K. Marx

Wage Labour and Capital, K. Marx

Discussion Questions:

- What problems does “production for exchange” rather than “production for use” create in society?

- How does exploitation manifest in your job? Who appropriates your surplus value and how can you resist this?

- Imagine different acts of resistance against an employer short of revolution (e.g., moralising, lobbying, strike action, property damage, assassination, etc.) What are the limitations of these?

- How does the Labour Theory of Value differ from liberal economics? Why don’t universities teach the Labour Theory of Value as fact?

- Is the relationship between landlord and tenant comparable to the relationship between boss and worker? What are the similarities/differences?