Where materialism anchors our philosophical worldview in a scientific understanding of the relationship of matter to consciousness, materialist dialectics take us even further with a scientific theory of motion and development. Taken together, dialectical materialism allows us to correctly analyse the world around us, understand our past, resolve all sorts of problems in the present, accurately predict future events, and coordinate our efforts towards bringing forward a more advanced stage of human society: socialism.

In the words of Josef Stalin: “Dialectical materialism is the world outlook of the Marxist-Leninist party. It is called dialectical materialism because its approach to the phenomena of nature, its method of studying and apprehending them, is dialectical, while its interpretation of the phenomena of nature, its conception of these phenomena, its theory, is materialistic.”

In Ancient Greek society, dialectics was the act of debate and discussion to establish the truth by uncovering contradictions between two philosophers, with the word “dialectics” coming from the Greek word dialektos meaning “talk”, “conversation”, or “speech”.

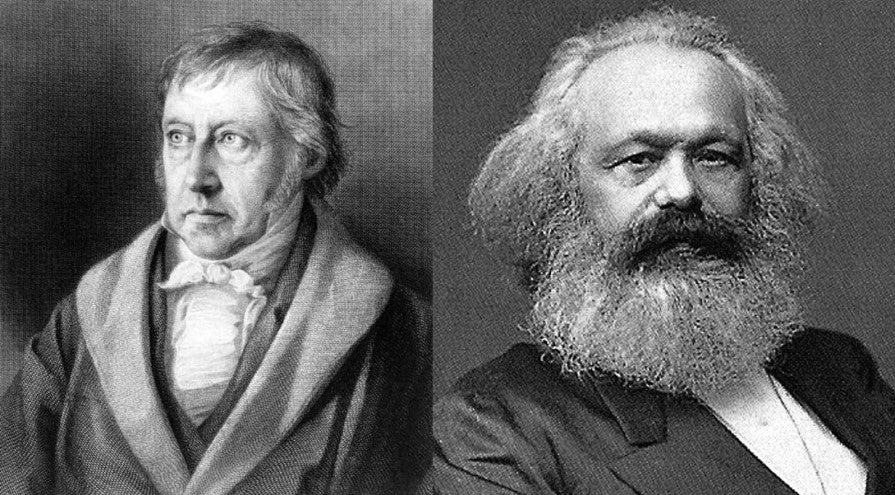

Dialectics as a structure of conversation has a long history of study, but where Marx comes into play is his inversion of the dialectics of the German philosopher Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel, the predecessor of a pioneering group of philosophers in Germany known as the Young Hegelians. In short, Hegel considered development to be a product of the contradictions inherent within the realm of thought, consciousness, and what he termed “the Idea”. As Marx later explained, Hegel’s idealist dialectics was therefore “standing on its head” and needed to be grounded in materialism to be scientific and useful. Marx and Engels’ materialist dialectics proceeded from this point.

Universal Connection and Motion

Supporters of dialectical materialism waged a particularly strong ideological struggle against metaphysics, which promoted a one-sided and static view of the world which ignored the fact that everything in the universe, from atomic nuclei to galaxies, is interconnected. Nothing exists in isolation, and all things are in a state of motion and development. Stalin described this as follows:

“Contrary to Metaphysics, dialectics does not regard nature as an accidental agglomeration of things, of phenomena, unconnected with, isolated from, and independent of, each other, but as a connected and integral whole, in which things, phenomena are organically connected with, dependent on, and determined by, each other.”

“The dialectical method requires the consideration of an all-sided point of view. If you’re observing something, you have to consider its history, where it came from, nothing stays still, everything is in a ‘state of continuous movement and change, of continuous renewal and development, where something is always arising and developing, and something always disintegrating and dying away.’”

When we study an object by removing it from its natural environment and analysing it in a lab, we can sometimes miss the bigger picture. For instance, you might categorize and examine every cell of a plant and feel confident that you understand it completely. But is this a complete view of its species? How do we understand the environment that shaped it? Can you understand a hive by looking at a single bee? A tree from a leaf? A forest from a plant? All these levels are intricately woven into each other and in large part determine what shape a plant takes, how big it can grow, etc.

Removing a plant from its environment might tell us about its structure at that moment in time, but it strips away its context. To truly understand the plant’s development, we need to observe it in its ecosystem where it interacts with its surroundings. The same is true for everything.

Cause and Effect

An understanding of the universal connectivity of all things allows us to identify the different types of relationships between them, but these relationships may often be mistaken or deliberately obscured, leading to misunderstandings of reality.

One important type of relationship is cause and effect. A cause always comes first and an effect second, but just because one thing follows another does not mean that it is a causal relationship. For example, if I pray for rain and it starts raining, that doesn’t mean that a god has answered my prayers, although I may mistakenly believe so.

It is, however, a relationship of cause and effect when I press a light switch and the light comes on. The effect necessarily results from the cause, in that I must press the light switch for the desired effect, but this does not make the outcome inevitable. If the light does not come on, it is not because pressing the light switch is no longer the cause of a lit bulb, but because of some other cause interfering with the relationship, such as the fact that the bulb is broken. Relationships of cause and effect therefore require certain conditions to be met, and in this case, a working bulb is one of them.

It is also very important not to confuse an occasion or specific moment of an event for the cause of the event. For example, some people claim that Hitler’s appointment to the position of Chancellor of Germany was the cause of the rise of German fascism and the start of WWII, but communists recognise that German fascism was a product of much larger economic and class factors, so Hitler’s assassination before being placed in power would not have prevented the same outcome under a different leader. The same is true for international events. The conflict in Ukraine did not start with Russia’s military actions in February 2022, and the oppression of Palestine did not start with resistance actions on October 7th, 2023.

Understanding causes properly is the guiding motive of all science as well as a core skill of all good communists. It is difficult, but necessary work to analyse all aspects of a given situation fully to understand the real factors at play and to be able to distinguish genuine causes from mere conditions and occasions.

Interaction

To fully grasp materialist dialectics, analysing the world metaphysically through the lens of cause and effect is not enough. Moreso, we must seek to analyse the complexity of the world through the concept of interaction. Since the whole universe is interconnected, every cause is also the effect of something else, and every effect is also a cause. For example, my pressing the light switch may have been caused by the darkness of the time of day, and the light in my room will be the cause of countless other effects on the world around me.

Sometimes, a cause and effect may change places, with the latter becoming the cause of the former. For example, under capitalism, greater demand for a commodity leads to greater production, but the increase in production then produces increased demand. Demand therefore affects production and vice versa.

We must also recognise which factor is determining and dominant, as it is this which allows us to analyse all the forces together, see the path of development, and decide on a course for our own actions. For example, Marxists recognise that any given social structure is made up of an economic base (e.g., the mode of production) and a superstructure (e.g., the social institutions and ideologies which develop out of it). Marxists also recognise that there is an interaction between these two forces, but that the economic base is dominant. While ideological elements of capitalism, such as schools and the media, reinforce capitalism, and we should build working-class education and media in response, it would be a mistake to believe that the capitalist institutions could ever be replaced completely without the revolutionary transition to a socialist economy, so any working-class structures we do build must be coordinated towards this goal.

Necessity and Accident

It is also important to understand the concepts of necessity and accident. For example, if I drop a stone, it is a necessity that the law of gravity will cause it to fall towards the Earth, but laws can only ever be general truths which do not take into account every specific situation, and the stone may fall slower, stop, or even rise into the air when certain environmental conditions are met.

It is a general law that under capitalism, working-class people cannot escape their class position, but that doesn’t stop the occasional worker from accidentally winning the lottery, buying a business, and joining the ranks of the capitalists. Laws of necessity must always be viewed through this lens to prevent both extreme misinterpretations: that laws always result in the same outcome, and that the world is just a series of random accidents.

Quantitative and Qualitative Change

In philosophy, a quality is every essential feature that makes a particular thing what it is and distinguishes it from others. For example, two of the qualities of an orange are that it is orange when ripe and that it grows on a tree. Things also have quantitative aspects which can be counted and measured, such as the orange’s size and weight. Metaphysics fails to recognise the connection between qualities and quantities, but dialectics understands the interaction between them. In general, it can be said that quantitative changes lead to changes in quality.

Describing dialectical development as a transition from quantitative changes to qualitative changes, Engels says: “In physics… every change is a passing of quantity into quality, as a result of a quantitative change of some form of movement either inherent in a body or imparted to it. For example, the temperature of water has at first no effect on its liquid state; but as the temperature of liquid water rises or falls, a moment arrives when this state of cohesion changes and the water is converted in one case into steam and in the other into ice.”

Changes in quantity can often be very gradual and even imperceptible, and it is not until the change in quality that there is a clear and radical transformation, known as a leap which may appear much faster in comparison. We can also use the words “evolutionary” and “revolutionary”, especially when describing social change. To understand how revolutionary transformations in quality occur, it’s necessary to identify the evolutionary changes in quantity that lead to them.

For example, a revolution from capitalism to socialism requires that the contradictions present in the former mode of production be sufficiently acute, and that the working-class organisations and Communist Party all be sufficiently developed. Realising this completely undermines the arguments of both the reformist socialists, who argue for evolutionary changes without a revolutionary leap, and the various utopians, idealists, and ultra-leftists, who argue for revolutionary leaps before the necessary material conditions and evolutionary developments are complete.

Contradictions

But understanding that quantitative changes lead to qualitative changes still fails to address the driving force behind this change. To find the answer, we must look at the contradictory nature of reality itself. Even ancient philosophers in China, India, and Greece recognised that contradictions do not only exist side by side, but can also exist united in one and the same object or phenomenon, as different faces of the same thing. The idea that the collision of such opposites is the motive force of change was already expressed in antiquity, such as by the ancient Greek philosopher, Heraclitus, who said that “everything happens through struggle” and that struggle is the “father” of all things. This anticipates Lenin by thousands of years, who said that “development is the ‘struggle’ of opposites” and that this is the “essence of dialectics.”

When Marxist-Leninists describe dialectical contradictions, they are talking about those conflicts of opposites which exist united in one and the same thing. For example, the leaf of a plant may appear static and still, but when looked at under a microscope, its cells are constantly undergoing a process of death and renewal, opposing but complementary aspects of growth and change. In the words of Engels: “There is a contradiction in a thing remaining the same and yet constantly changing, being possessed of the antithesis of ‘inertness’ and ‘change.’” Just like the process of evolution, the development of matter is therefore not merely a result of external, but also internal motivations which as a general law take the matter from simple stages to complex stages and lower stages to higher stages. This is the essence of progress.

To understand something’s development, it is also necessary to identify the principal, determining contradiction within it, and what form that struggle takes. This requires a concrete analysis which can be developed like any other skill, allowing us to identify any progressive, revolutionary aspect of a contradiction that should be actively supported.

We must also recognise the difference between antagonistic and non-antagonistic contradictions. Non-antagonistic contradictions are a feature of life in general, with humanity always having problems to solve. Without them, we would have nothing driving us forwards. On the other hand, antagonistic contradictions represent the contradictions between those things which are fundamentally irreconcilable. The most obvious example under capitalist society is the antagonism between the capitalist class, which wants higher profits and lower wages, and the working class, which wants lower profits and higher wages. Liberals and reformist socialists who believe in the peaceful reconciliation and co-existence of these classes are therefore living in a fantasy. In the words of Lenin, “Antagonism and contradiction are by no means the same thing… Under socialism the first will disappear and the second will remain.”

Let’s apply what we’ve learned to the British political system as an example. At first glance, it may appear that in a society mainly divided between Labour seats and Tory seats, the principal, antagonistic contradiction is represented by the battle between these two parties. However, a closer analysis reveals that this is in fact a non-antagonistic contradiction. The two parties merely represent two factions of the ruling capitalist class who conspire to extract profit from the workers by different means. Neither represents the progressive, revolutionary force capable of resolving the contradictions inherent to British capitalism to qualitatively change the British mode of production.

The principal, antagonistic contradiction in the British political system therefore lies not between Labourites and Tories, or liberalism and conservatism, but between proletariat and bourgeoisie, or socialism and capitalism. This means it is the responsibility of all progressive forces in Britain to unite the whole working class, regardless of political identity, behind an independent political organisation with the strength to overthrow all factions of the bourgeoisie through socialist revolution.

Dialectical Negation

Finally, negation is the law-governed replacement in the process of development of an old quality by a new one, often taking the form of the transformation of a thing into its opposite, with Marx writing that “no development that does not negate its previous forms of existence can occur in any sphere.”

The struggle of contradictions must therefore result in the negation of one quality by its opposite, leading to new contradictions and new negations. Dialectical negation, meaning the development into something new as a result of the struggle of internal contradictions, must be differentiated from mechanical negation, which means destruction through an external force. A bug may be negated by being crushed, for example, which would end its development.

Since dialectical negation means a continuation of development, something within the object of negation must be preserved alongside the thing which is destroyed. Communists recognise that socialism is not created out of thin air, and can only be built with the tools provided under capitalism. The revolutionary transition to a socialist society will therefore preserve those elements from capitalist society which are progressive and useful, while destroying those which are reactionary and harmful.

Negation may also mean a return to old forms at a higher stage of development. In his work Anti-Dühring, Engels explains this using the example of a grain of barley. If a grain of barley falls on the right soil with the right conditions, it will be negated and turn into a sprouting plant. This sprouting plant, at the end of its development, will then be negated again, leading to the death of the plant and many more grains of barley than there were at the beginning. In this way, the negation of the negation leads to an old form but at a higher stage of development. Similarly, communists seek to establish a classless society, but thousands of years more advanced than the primitive communism before class society developed.

These are the fundamental laws of dialectics which allow communists to create an accurate picture of reality to guide their actions. We must remember, however, that a dialectical materialist analysis is a practical skill which must be trained through conscious effort.

Further Reading:

Anti-Dühring, F. Engels

Dialectics, T. A. Jackson

On the Question of Dialectics, V. Lenin

Phenomenology of the Spirit, G. Hegel

The Three Sources and Three Component Parts of Marxism, V. Lenin

On Contradiction, Mao Zedong

Dialectical and Historical Materialism, J. Stalin

Discussion Questions:

- Can you think of an example of a historical or international event where the cause has been deliberately misrepresented by the ruling class? What was the real cause and the factors which led up to it?

- Can you think of an interactive relationship between two things? Which can be described as dominant?

- What accidents under capitalism can be misrepresented to argue that socialist revolution is not a necessity?

- To support a socialist revolution in your community, what quantitative and qualitative changes would need to be made?

- Can you give an example of an antagonistic and non-antagonistic contradiction? How could these be resolved?