Dennis Broe reviews two Netflix original TV series, Green Frontier and Wild District, shockingly different approaches to South American struggles for political liberation. This article first appeared on Culture Matters.

Two series from Colombia, Green Frontier and Wild District, both Netflix originals and both made by the same production house, Dynamo, stake out the left and right of Colombian politics.

The iconography of the progressive series, Green Frontier, links it with a history of Latin American films dealing with the continent’s indigenous peoples, a part of the tradition of Magical Realism which charts the expression of indigenous cultures in a colonized landscape. The theme of the series is the destruction of the Amazon on the Colombian-Brazilian border, and a lost tribe trying to ward off the loggers who would destroy them and the forest, along with the deeper, more insidious and more persistent menace of Western colonialism.

Wild District on the other hand employs the iconography of the American action film in its more reactionary and caricaturing forms. It depicts guerilla forces as savages, and its characterization of the slums of Bogota is racist and classist – just another jungle, as primitive and untamable as the actual jungle inhabited by the rebel group FARC, rather than the habitat of one of the continent’s poorest and most deprived populations.

Progressive ecological and political awareness

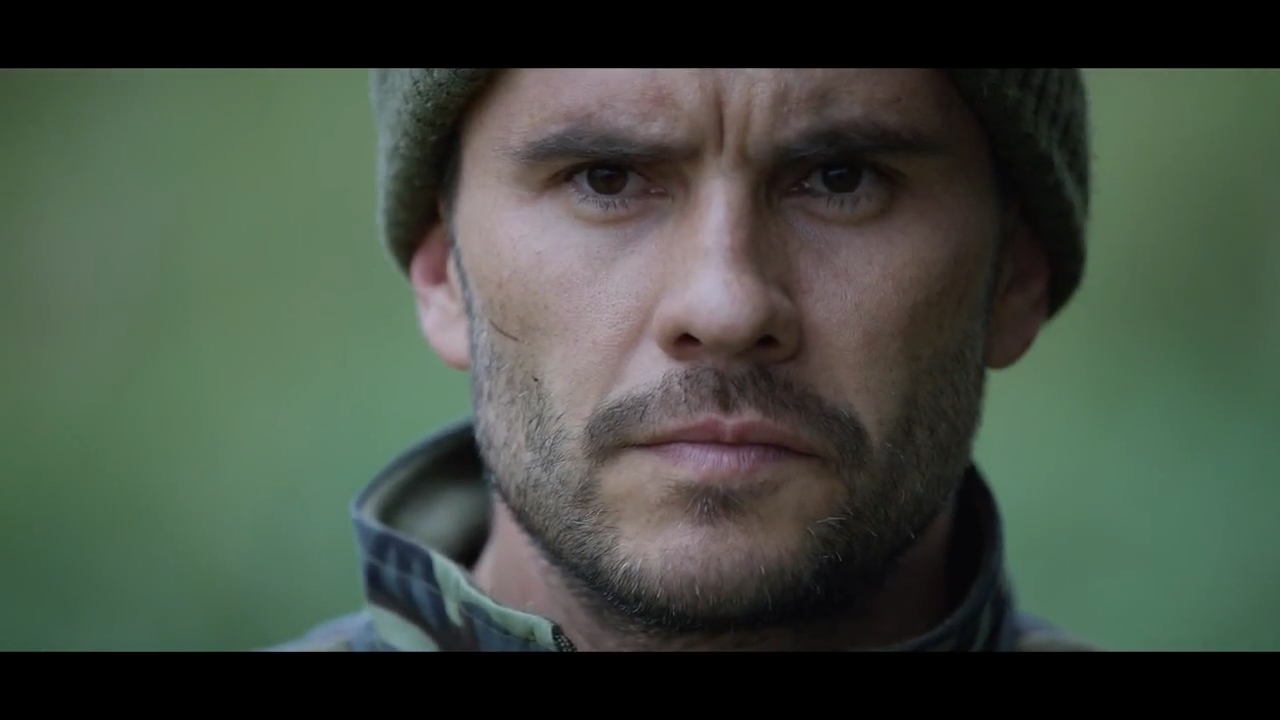

Since both series are Netflix originals, it would seem the streaming service is interested in covering all bases. With the more independent, left-field Green Frontier, whose pilot is directed by the superb Ciro Guerra, it’s trying to attract a progressive audience who are committed to the ecology of preserving the rainforest and the country’s indigenous people. With the straightforward action series, which boasts a superb performance by Juan Pablo Raba, veteran of Narcos, the service seems to be playing to the populist and far right, in a show that openly rationalizes the work of the death squads, an auxiliary of the former Uribe government.

The pilot of Green Frontier owes much to Guerra’s visual acuity and his thematic concerns. His first global success, the film Embrace of the Serpent, was about the relationship between two aging members of their respective civilizations. One was a German social scientist in the jungle at the turn of the last century, in the vanguard of what would become a pillaging and patenting of its secrets for Big Pharma, and the other was his guide, an indigenous last member of a tribe wiped out by the European colonizers. The indigenous guide recalled this devastation in a series of scattered images that operated more from an intuitive and unconscious logic than the Western scientist’s rational mapping of this world. In Green Frontier a warrior, one of the last members of his tribe, communicates with a female member both in this world and in another, with the otherworldly images shown in a negative silvery tint.

Guerra’s second film, Birds of Passage, adopts codes from the gangster film to recount how an Amazon tribe succumbs to the profit-making inducements of the drug trade and how the ensuing greed for material objects utterly demolishes their centuries-old customs and ways of life. It’s The Godfather or Scorsese’s Casino in the jungle, as it maps the changes wrought by money. It is even closer to Gangs of Wasseypur, a stunning Indian film about the changes in an Indian province over 40 years by the introduction of a profit-making gangster economy.

Green Frontier also presents the jungle under attack from the loggers who are stripping its assets, from a mysterious white man who is a demon with a history that extends back to the Nazis, and from the local corrupt police whose leader “Uribe” orders the killing of the Bogota female agent who instinctively acts to protect the jungle.

The series opens with the slaughter of both an indigenous woman Ushe and a group of nuns and is in the present an investigation by the Bogota agent Helena and her partner Reynaldo, who has been outcast from his indigenous community, into the killings. A flashback narrative recounts the relationship of Ushe and Yua, the male protector of the jungle. The jungle itself is defined as both holder of the secret of life and as female.

The flashbacks are not so much backstory, as they would be in a more Euro-centered narrative, as they are a parallel world with the jungle itself acting to protect Yua and at times making him invisible. The series is elegantly filmed on the Colombian-Brazilian border and the loggers, whose boisterous chainsaw at one point interrupts a conversation between Ushe and Yua, are the visual and aural sign of the Bolsonaro-Trump assault on the environment, waged in the Brazilian case against the rainforest and in Trump’s case against public lands which he is now opening to drilling and mining.

The series ends with an epic battle between the Bogota agent Helena, now in touch with her roots in the earth and allied with the jungle, and the white demon Joseph, a remnant of the Nazis, the ultimate degradation of Western civilization. It’s a monumental struggle and one those who want to save the earth are engaged in each day.

Far-right nonsense

Wild District on the other hand is far-right nonsense that misses completely the changes that are going on in Colombia, a traditional bastion of Latin American conservatism and a U.S. ally which is in the process of attempting to get out from under the thumb of its history of violence and right-wing death squads. The recent arrest of the hit-squad aligned former president Alfaro Uribe for corruption is a sign of these changes.

The question in Colombia at the moment is the question of peace as the FARC, the revolutionary guerrillas, have been more than willing to lay down their arms and accept a peace deal in order to challenge the right wing at the polls as a political party. However, despite overwhelming popular support for the peace process, the current president Ivan Duque, a protégé of Uribe’s, opposes it and allows the guerrillas to be assassinated by still highly active right-wing killers as the former guerillas, having surrendered their weapons, are now defenseless.

None of this is even hinted at in Wild District which is not much more than a sounding board and rationale for far-right sentiment and continued slaughter in the country. The FARC are portrayed as bloodthirsty kidnappers of children, ignoring any rooted connection they have with the peasantry, and as simply sadistic killers and grudge-bearing executioners of those who would desert them, forgetting that the FARC as a unit has pushed for peaceful disarmament. There is no mention of the far-right death squads who hunt them.

The series is so far right it would have difficulty even finding a place on the Fox Network, though it might fit comfortably in an evening slot on the Fox News Network between discredited Fox commentators Bill O’Reilly and Megan Kelly. This series makes Jack Webb, the McCarthyite-era creator of Dragnet, look like Bernie Sanders. It lacks the subtlety of even a 24 or a Homeland where at least the ideological message is more complicated, and subtly obscured.

Its one positive feature is the lead character, Jhon Jeiver, a “light foot” FARC former assassin who creeps up on everyone but whose effort to insert himself into everyday life is touching and includes his attempt to reestablish a relationship with his son. In a well-drawn scene in the market where he has found work, Jhon tells a female customer seeking a solution for a burn to forget a pharmaceutical remedy, and instead shows her how to apply the healing plants aloe and calendula (marigold) that he learned in the jungle. His nemesis on the series is of course the snivelling, sadistic jungle revolutionary who wants to continue the fighting, the exact opposite of the contemporary Colombian reality.

The difference in the two series is strikingly apparent in the use of the names of the Colombian leaders. In the far-right Wild District, “Duque,” the current leader now accused in the press of corruption and who opposes the peace process, is the name of the tough on the outside but heart-of-gold female detective who is Jhon’s handler. In Green Frontier, “Uribe” is the corrupt head of the local police who orders the assassination of Helena, the eventual protector of the jungle and of the authentic Latin American heritage.

The ideological difference between the two series is shocking, although ultimately of course both series contribute to the profits of Netflix. However, there is still a stark contrast between two views of Latin America. Green Frontier is allied with the Bolivarian Revolution which attempts to redistribute wealth and raise the living standard of the continent’s poorest, often those with an indigenous or African background. Wild District aligns itself with the Bolsonarian Revolution which attempts to sell off both the natural and cultural heritage of the continent in its return of wealth back to the richest.

One revolution attempts, as does Helena, to preserve the continent. The other, which like Wild District characterizes all efforts at change as savage, instead attempts, as can be seen in the murderous spread of the coronavirus out from Brazil to its neighbours, to destroy the continent and keep it under the colonial heel.

Dennis Broe

This article first appeared on Culture Matters.