[Adapted from a talk first delivered at the 2026 Red Books Day event hosted by Manifesto Press, Saturday 21st February]

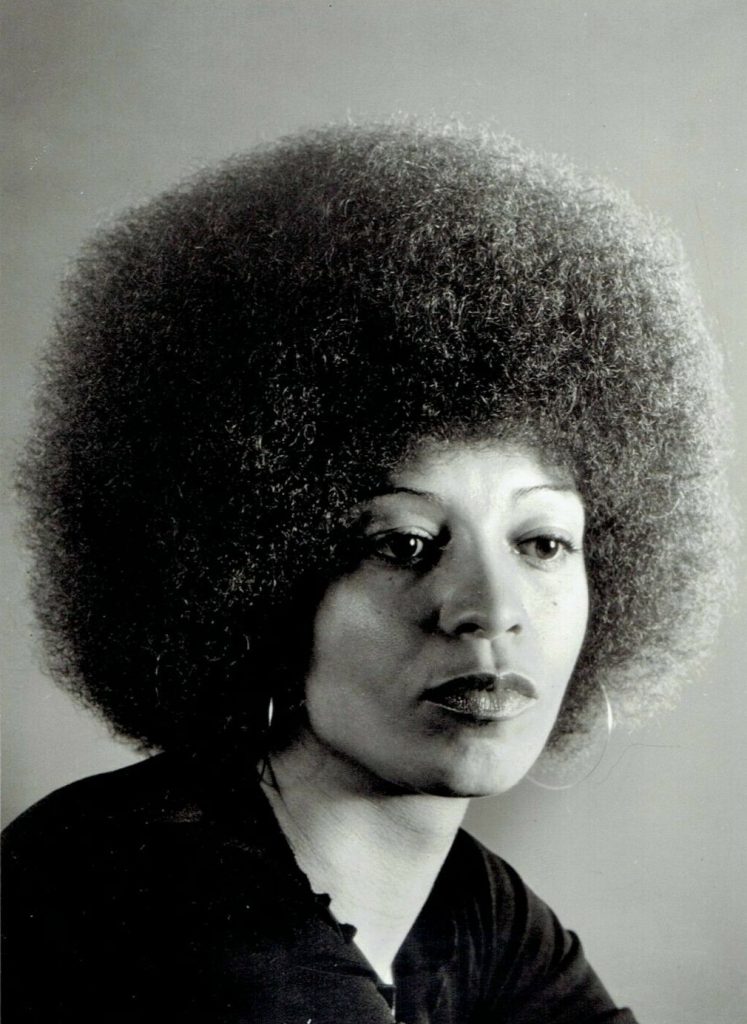

Angela Davis’ Women, Race and Class is a book I first read five years ago, and have recently reread to refresh myself on. It is a masterclass in tracing the unique and understudied experience of Black women in the US, from slavery to super-exploitation and oppression of Black women today. Davis clearly outlines how the struggles for Black and women’s liberation are interconnected, if often racistly and erroneously juxtaposed to each other, under capitalism. She warmly evidenced the genuine revolutionary solidarity between Black and white (working-class) women, whilst simultaneously holding mainstream feminism to account for its racism and exclusion of Black women. This contradiction is a recurrent theme, demonstrating the historical difficulties the anti-racist struggle has faced that persist today.

I often remark that being good on one issue, like opposing slavery, does not mean that you are (consistently) good on others.

Davis provides examples of this. The anti-slavery movement in the US was largely led by white, middle-class women, who had the time to do so. Yet, many of these campaigners were deeply racist when it came to Black men getting the vote before them, falling back on racist stereotypes that Black men are not intelligent enough to be deserving of the vote before white women. They should have been fighting against these stereotypes, like their Black sisters were. Black women at the time understood that suffrage for Black men was a step forward for all Black people.

This exclusion persisted. Black women were shut out of both the mainstream feminist movement and the labour movement, largely because the majority worked as domestics and fieldworkers, not in factories, for the white middle-class women who led the feminist movement. Therefore, they were never prioritised to be organised. The Communist Party itself was not immune to these failings. Davis highlights Communist leader and historian William Z. Foster’s admission that the Party in the early 1920s was ‘neglectful of the particular demands of Negro women in industry.’

However, Black women Communists and their white sisters, led the charge on organising Black women workers. Davis charts the development of this work as over the next decade. Communists began to recognise the centrality of racism in US capitalism, developed a serious theory of Black Liberation, and developed a consistent record of anti-racist campaigning through figures like Claudia Jones. Capturing this development is crucial, not just to understand our own Communist Party tradition, but to build towards our own growth today. The labour movement weakens itself if it refuses to recognise these issues and be divided by the historical seepage of capitalist values on race and sex lines.

The campaign for reproductive rights, on the surface, was a movement to free all women, especially working-class women, from unwanted pregnancy. But Black women were deeply distrustful and largely uninvolved, which Davis explores the origins of. The white-led movement had not considered, and importantly had not cared enough to ask, about the US’s history of forcibly sterilising Black women to control the Black population. The reproductive rights’ movement centred on the right to not have children, but Black women wanted the right to have children. To build a mass women’s movement today, it is vital that it is led by Black and white working-class women, built on a foundation that acknowledges differences based on inequality in order to eradicate their causes, rather than denying or ignoring them.

So why does the book mean so much to me? This book was useful to my early political development because it taught me to be critical of movements that I might instinctively support, rooted in the works of Marx and Lenin. Davis’s revolutionary optimism closes the book with a vision for socialism in which women are liberated from the drudgery of housework and the double burden to ensure equality of the sexes. Only by knowing the past can we fight for a revolutionary future.

Georgina Andrews, is General Secretary of the Young Communist League

Consider reading Women, Race and Class in your branch or book club, discussing the questions below and coming up with more of your own:

- For those of you who know the book, what was the passage or idea that most struck you, or made you think differently? For those new to it, was there anything in the introduction that surprised you or that you want to know more about?

- I spoke about the idea that ‘being good on one issue doesn’t mean you’re good on others.’ Davis shows this through the fraught relationship between the women’s suffrage movement and the struggle for Black liberation. How do you see that historical tension today?

- How do we ensure that our own organising today isn’t just focused on the ‘traditional’ industrial worker, but organises those in precarious work, domestic work, and the gig economy—roles still disproportionately held by women and Black workers?

- For us, as communists and campaigners, what is the main takeaway from Women, Race and Class for our work today? How does this book help us build the kind of united, working-class movement capable of not just fighting back, but winning?