To begin understanding the working-class worldview of Marxism-Leninism, we first need to discuss the philosophy on which it is based. After all, how can we seek to change the world without the tools we need to understand it? The result of centuries of investigation and ideological struggle have led communists to one rational philosophy above all others: dialectical and historical materialism.

Since the time of the Ancient Greeks and before, a great battle has been waged between two different camps of philosophy: science and superstition, logic and irrationality, fact and fantasy.

In one camp, the idealists believed that the world depended on some form of consciousness, whether of men or of gods, and that consciousness came first and matter second (if matter existed at all). In the other camp, the materialists fought to show that consciousness and matter were separate, that matter came first and consciousness second, and that consciousness was a reflection of the material world, rather than the material world itself. In antiquity, Plato was an example of an idealist, and Aristotle, a materialist.

As Lenin wrote in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism: “Materialism is the recognition of ‘objects in themselves’ or objects outside the mind; the ideas and sensations are copies or images of these objects.” “Matter is that which, acting upon our sense-organs, produces sensation; matter is the objective reality given to us in sensation… Matter, nature, being, the physical—is primary, and spirit, consciousness, sensation, the psychical—is secondary.”

Materialism is also the realm of science, and dedicated scientific investigation when performed correctly will naturally lead scientists to adopt a position of spontaneous materialism: unconsciously applying materialism to understand the laws of the world around them, although even this can lead to repression and hostility. For example, Copernicus established that the Earth revolves around the sun, despite also being devoutly religious throughout his life. Seen as a threat against the Catholic Church, the Inquisition then waged war on his supporters, including Galileo, to try to make them renounce their views.

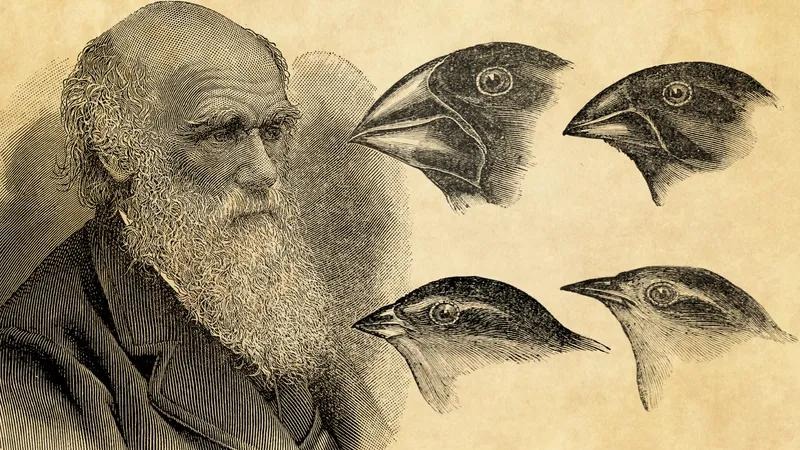

As opposed to the Enlightenment, which was an era of progressive victories of rational thought over faith and superstition supported by the capitalist class against the church, the capitalists have now begun to fight against the application of materialism to the social sciences. Rather than recognising that dialectical materialism is a scientific development which, like Darwin’s theory of evolution, disproves and makes redundant all previous theories, capitalist intellectuals have instead presented philosophy and sociology as matters of opinion and personal choice which are not subject to the laws of other scientific fields. This is because to do otherwise would be a direct threat to their power.

Under capitalism, every tool in the capitalist arsenal, including the education system and the media, is therefore used to prevent workers from reaching the simple, scientific conclusion that dialectical and historical materialism leads us to: that Marxism-Leninism is correct, and that capitalism is just one phase of human history that anticipates the overthrow of the capitalist class by the workers and the revolutionary transition to socialism.

Dialectical and historical materialism is the highest stage in the development of philosophical thought so far, but the perfection and refinement of materialist philosophy has taken thousands of years. Materialism emerged about 2,500 years ago in China, India, and Greece, and was closely linked with people’s everyday experience of interacting with nature and gaining knowledge from it. But this was a very basic and accidental form of materialism.

It wasn’t until the 17th and 18th centuries that materialism became much more mature. The materialists of this period, such as Diderot, Hobbes, and Newton, were all heavily influenced by advances in mathematics and the mechanics of terrestrial and celestial bodies, which led to their generalised views about matter and motion. These philosophers and scientists all saw both nature and society as the products of these mechanical laws and hoped to use them to explain natural and social phenomena, leading to what became known as mechanical materialism.

Despite being a great advance on previous theories, Engels pointed out three basic limitations of the mechanical materialists. Firstly, they tried to reduce all processes to general laws of mechanical motion, failing to understand the specifics of nature and society. Secondly, their philosophy was metaphysical, in that it could not properly understand development, and saw nature as something fixed and unchangeable which constantly repeated the same cycles. Finally, they failed to see the material, economic, and class basis of social development, instead viewing social progress as a direct result of the accumulation of knowledge by extraordinary individuals.

Another great advance came with philosophers in the early nineteenth century, such as the German atheist philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach, who was able to advance beyond the mechanistic limitations of his predecessors. However, Feuerbach could not surpass their other defects and failed to link his ideas up with practical social and political activity. It wasn’t until Marx and Engels that, under the influence of the ideas of the philosopher Hegel, materialism was combined with dialectics to form dialectical materialism, which will be explored in the next chapter.

Dialectical materialism also differentiates itself from dualism, which argues that matter and consciousness are equal and completely separate, rather than interconnected entities in which matter takes precedence; as well as vulgar materialism, which sees consciousness as a type of matter, rather than a reflection of and a property of matter.

Without ever confusing the two, communists recognise the interconnected nature of matter and consciousness, and this becomes particularly important when it comes to understanding the transformative power of labour on our minds. For example, as human beings performed increasingly complex acts of labour, this stimulated the development of our brains, which thus made the labour we could perform more advanced.

In the words of Mao Zedong, “If you want knowledge, you must take part in the practice of changing reality. If you want to know the taste of a pear, you must change the pear by eating it yourself… If you want to know the theory and methods of revolution, you must take part in revolution. All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience.”

It should also be stated here that although Marxism-Leninism is fundamentally incompatible with idealism of all kinds, and although communists must both uphold and promote a materialist worldview, communists also recognise that, since consciousness is a reflection of the material world, reactionary and anti-materialist ideologies are largely a product of the society in which people are raised, and therefore cannot disappear completely until the material and economic conditions which gave rise to them are dismantled. So long as church and state are kept separate and personal beliefs are not harmful to others (such as with racist ideologies or dangerous cults), freedom of belief has therefore been carefully protected in all socialist societies, from the Soviet Union to the People’s Republic of China.

Further Reading:

Socialism Utopian and Scientific, F. Engels

On Practice, Mao Zedong

Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, V. Lenin

Elementary Principles of Philosophy, G. Politzer

Discussion Questions:

- What is the difference between idealism and materialism?

- Can you give any examples of idealism today?

- How does idealism cause harm to the workers’ movement and the communist party?

- When analysing a problem, what steps can we take to ensure that our solutions are guided by materialism?

- How should we approach different types of idealism in the workers’ movement?