In 1924, Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik Party and main inspiration of the October Socialist Revolution, died having seen the formation of the world’s first socialist state and its survival amidst civil war. The USSR was at a crossroads. Expected revolutions in Germany, Italy, Poland, and other advanced capitalist countries had failed, leaving the USSR isolated and surrounded by capitalist enemies. The question of whether it was possible to build socialism in these conditions was paramount.

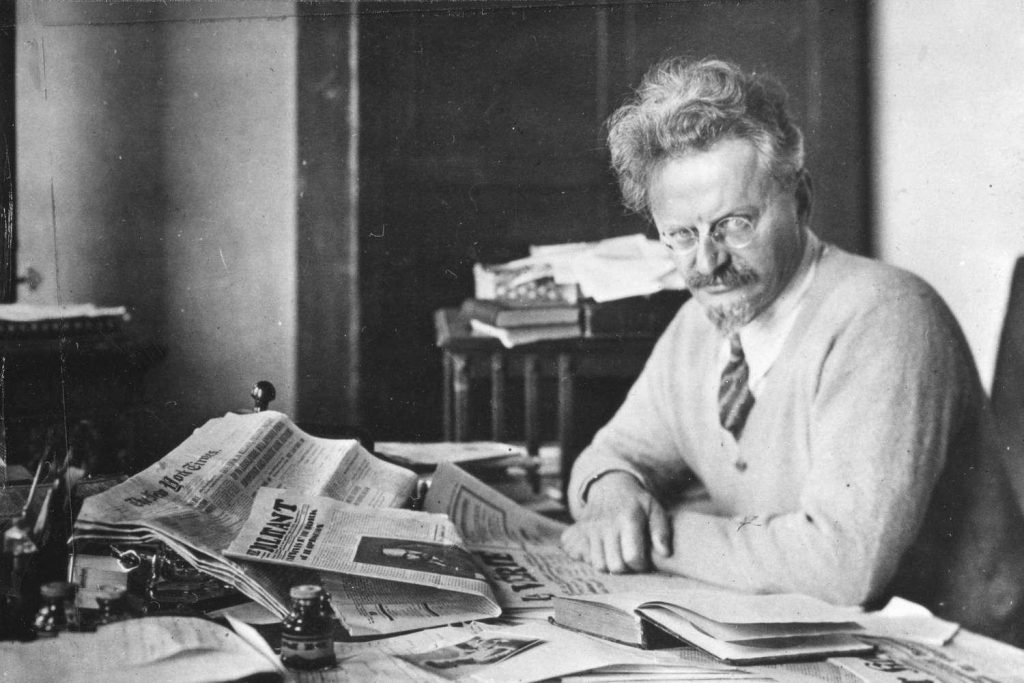

Two competing theories arose with different answers—the theory of Socialism in One Country by Josef Stalin and the theory of Permanent Revolution by Leon Trotsky, with both claiming to be a true continuation of Lenin’s ideas while denouncing the other as a revisionist aberration. Trotsky’s support for Lenin was actually a recent development, as before the Bolshevik Revolution, Trotsky had described him as a “professional exploiter of every kind of backwardness in the Russian working-class movement”, stating that the “entire edifice of Leninism at the present time is built on lies and falsification and bears within itself the poisonous elements of its own decay”.

But to address the theoretical disagreement on its own merits, the debate around the possibility of constructing socialism in one country relates to the Marxist position on internationalism. One of the best-known lines of the Communist Manifesto puts forward the idea of proletarian internationalism, stating that “The Communists are further reproached with the desire to abolish countries and nationalities. The working men have no country. We cannot take from them what they have not got.”

In Marx’s time, Britain and Germany were the world’s most advanced capitalist countries, and it was widely believed that the sharpened antagonisms between bourgeoisie and proletariat in these countries would lead to an era of revolution. Since Western Europe dominated most of the world at the time, revolution would have meant a serious breakdown of international capital. However, by 1924, revolution had not materialised in Western Europe. The question for the Bolsheviks became: now what?

Socialism in One Country was the answer of Stalin and other Bolsheviks to the question “can the USSR build socialism without revolution in Western Europe”. Their answer was yes.

Socialism in One Country is formulated according to Leninist principles, particularly Lenin’s concept of uneven development: “Uneven economic and political development is an absolute law of capitalism. Hence, the victory of socialism is possible first in several or even in one capitalist country alone.” Marx and Engels did not theorise this to be possible, but Lenin recognised that the development of imperialism had sharpened contradictions in a way that was different from Marx’s time. Imperialism had spread the antagonistic contradictions at the centre of capitalist countries to colonial and semi-colonial countries, spurring revolutionary forces in underdeveloped nations.

In consolidating the theory of Socialism in One Country, Stalin analysed two contradictions in Russia: internal contradictions between proletariat, peasants, landlords, and capitalists, and external contradictions between Russia and other capitalist countries. According to Stalin, Socialism in One Country meant “the possibility of solving contradictions between the proletariat and peasantry by the capacity of the internal forces of our country… it means the possibility of the proletariat seizing power and using that power to build a complete socialist society in our country, with the sympathy and the support of the proletarians in other countries, although without the preliminary victory of the proletarian revolution in other countries.”

On the other hand, Permanent Revolution was Trotsky’s answer to the question “can the USSR build socialism without revolution in Western Europe”. His answer was no.

Trotsky believed that socialism could not succeed in the USSR because Russia was a peasant country and therefore lacked the developed industry and working class necessary for socialism. He argued the USSR would have to make a deal with the advanced capitalist powers to access the international capital he believed necessary to build socialism. The idea of “Permanent Revolution” is based on Trotsky’s notion that the permanence of Russia’s revolution could only be guaranteed by revolution in the advanced capitalist countries, therefore in his mind, Russia either had to wage revolutionary war against them, or delay Russia’s own development until revolution took hold there.

Other Bolsheviks criticised Trotsky’s theory because of three elements. Firstly, it was defeatist and denied the strength of Russian workers and communists to build socialism. Russian workers had already established a dictatorship of the proletariat and resolved contradictions with the peasants by nationalising land, so the two main classes in the USSR were united in socialist construction. Secondly, Socialism in One Country was key to international revolution. Building socialism in the USSR provided a revolutionary base for the international proletariat, acting as an example for others in different countries, as well as providing material support to revolutions all around the world. Thirdly, Trotsky ignored the national task of the revolution. The national and international tasks of the proletariat were intertwined—you couldn’t build socialism internationally without building it in individual countries.

At the 14th Congress of the Bolshevik Party, the question of whether Russia should industrialise and develop socialism or stick to agricultural production as part of the international capitalist system was the main point of contention. After much debate, communist delegates voted in favour of socialist industrialisation—defeating Trotsky’s faction. The USSR would end the NEP and begin industrialisation in 1929, becoming the world’s second largest industrial power after the success of the first Five Year Plan and establishing a basic socialist system.

When Stalin died in 1953, socialism had been spread to countries across three continents, from East Germany to China. Socialism in One Country had become socialism for nearly half the world’s population—history had proven that the idea that socialism in one country could lead to socialism in many was correct.

The Trotskyist understanding of the impossibility of Socialism in One Country, held by many different groups in Britain who describe themselves as socialist or communist, leads to distorted analyses of existing socialist states and their governments, particularly the idea that without world revolution, a dictatorship of the proletariat will become degenerated or deformed and is no longer progressing towards socialism. The many different Trotskyist organisations in Britain, from the SWP and RCP to the SSP and Counterfire, are therefore broadly united in their ultra-leftist hostility to existing socialist governments and tacit support for their collapse. These organisations therefore tend to align themselves with imperialism against the socialist and anti-imperialist bloc, spending a lot of their time intellectually critiquing existing socialist countries. The only revolutions which have ever successfully overthrown imperialism and capitalism and led to lasting socialist governments which have made huge improvements to the lives of their citizens have been led by Marxist-Leninists, but Trotskyists dismiss these heroic achievements as “Stalinist” errors. In the words of Michael Parenti, “the pure socialists support every revolution except the ones that succeed.”

To cite just one example, following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Trotskyist organisations celebrated the event as a victory. Socialist Appeal, now the RCP, argued that it was a moment that “should have every socialist rejoicing”. However, the people of the former Soviet states found no reason to rejoice: the suicide rate rocketed by 50 percent in just a few years while the rates of infant mortality, unemployment, and premature deaths all hiked. For all the revisionist errors of later Soviet governments, it was the Marxist-Leninists who categorically opposed the counterrevolutions in Eastern Europe, understanding that working-class people would be hurt the most by capitalist restoration.

For Trotskyists, the collapse of the Soviet Union stands as direct proof that Socialism in One Country is inherently doomed. The examples of China, the DPRK, Vietnam, Laos and Cuba, however, disprove this falsehood. Despite facing immense pressure from the imperialist bloc through the likes of sanctions, military encirclement, and malicious anti-communist propaganda, the socialist and multipolar world continues to grow stronger than ever before.

Further Reading:

Blackshirts and Reds, M. Parenti

On the Opposition, J. Stalin

Trotskyism or Leninism?, J. Stalin

The Revolution Betrayed, L. Trotsky

Discussion Questions:

- To what extent is it true that Trotskyists support all socialist revolutions except the ones that succeed?

- Trotskyists often describe Marxist-Leninists as “Stalinists”. Did Stalin’s ideas differ from Marx and Lenin’s enough to warrant his own ideology? What about Trotsky’s?

- What is your experience with Trotskyist organisations in Britain? What is their class basis and what should our strategy be towards these different groups?

- Why is Trotskyism so prevalent in imperialist countries, rather than in the colonies and ex-colonies of the Global South?

- What makes Trotskyism attractive to workers? What makes it unattractive?