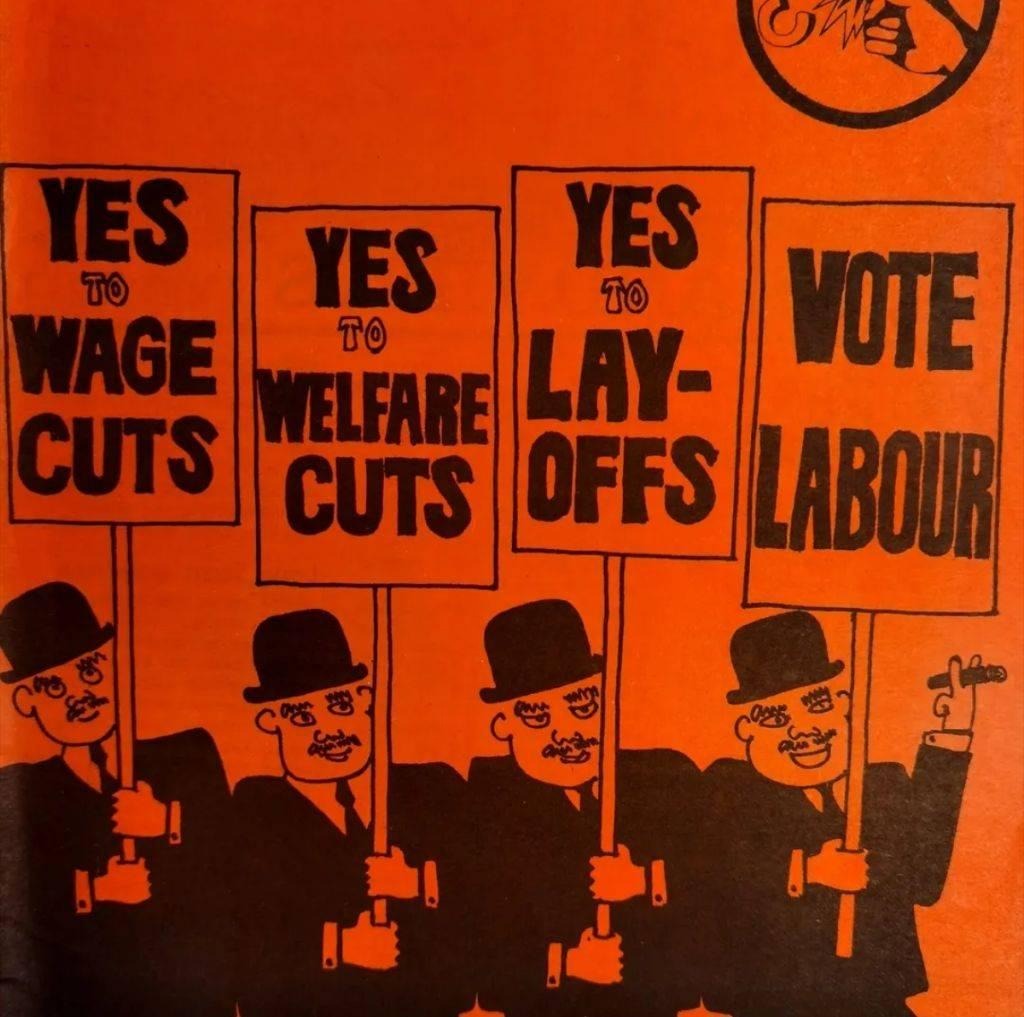

For British communists, the role and influence of the Labour Party cannot be ignored, as it has historically been the major party backed by Britain’s working class. With the affiliation, but declining influence, of several large trade unions, for many workers it has been seen as the only viable reformist vote in much of the country. However, the Labour Party is also an enabler and servant of British imperialism, a defender of the capitalist system, and a force for anti-communism. While there are Labour members who do not support this, and even historically some MPs, the party as a whole has proven hostile to social-democratic, let alone revolutionary efforts to change its direction, even preferring an electoral defeat than to win with a social democrat in charge.

The History of the Labour Party

The precursor to the Labour Party, the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) was founded after a motion passed at the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in February 1900 calling for the formation of a “distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to co-operate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour.” Representatives at the LRC’s founding included various trade union leaders on the one hand, and three political organisations on the other: the Independent Labour Party (ILP), the Fabian Society, and the Social Democratic Federation (SDF).

At this point, the TUC was still dominated by what Lenin called the labour aristocracy, a privileged upper stratum of the working class organised in the craft unions which defended the interests of skilled labour against unskilled labour, and tended to oppose worker militancy in favour of bourgeois respectability. New unionism, representing unskilled labour, was still a fairly new phenomenon, beginning with the strike wave ten years prior, and the most militant workers were still regularly blocked from TUC activity, such as when the more militant trades councils were banned from sending delegates to the TUC conference after 1895. At this time, the vast majority of unskilled workers were therefore not unionised, and those that were were unlikely to be represented at this elitist trades congress.

As for the “socialist” parties, the ILP represented by Keir Hardie (which had rejected the name “Socialist Labour Party”, considering it too off-putting to the upper-working class) had remained a party of liberalism, failing to perform any real political break from the old Liberal Party which it aimed to replace. Lenin described it as follows: “The petty-bourgeois craft spirit that prevails among this aristocracy of labour, which has divorced itself from its class, has followed the Liberals, and contemptuously sneers at socialism as a ‘utopia’. The Independent Labour Party is precisely the party of Liberal-Labour politics. It is quite justly said that this party is ‘independent’ only of socialism, and very dependent indeed upon liberalism.”

The Fabian Society, of which Keir Hardie was a member, was another right-wing organisation dominated by “middle classes”, intellectuals, and careerists, who described themselves as “socialist” only if socialism was stripped of all revolutionary militancy, considering socialism to be merely a left wing of liberalism. Engels described them as: “A clique of bourgeois ‘socialists’ of diverse calibres, from careerists to sentimental socialists and philanthropists, united only by their fear of the threatening rule of the workers and doing all in their power to spike this danger by making their own leadership secure… If afterwards they admit a few workers to their central board in order that they may play the role of the worker Albert of 1848, the role of a constantly outvoted minority, this should not deceive anyone.”

Despite its mixed politics, the SDF was the one nominally Marxist party at the LRC’s founding, with members including William Morris, James Connolly, and Eleanor Marx, and founded by Henry Hyndman after his reading of the Communist Manifesto. But as the only radical party in the LRC, the SDF had little influence over its direction. The SDF motion to the TUC’s 1899 congress arguing that the LRC should be a “party organisation separate from the capitalist parties based upon a recognition of class war” was comfortably rejected, agreeing to instead restrict itself to more “respectable” (unthreatening) activity as proposed by Keir Hardie. After agreeing not to stand in any Liberal Party seats at the 1906 general election, effectively acting as an appendage of the Liberals, the LRC renamed itself the “Labour Party” and the SDF promptly left, going on to support the founding of the British Socialist Party (BSP) instead. After briefly reaffiliating to Labour in 1916, the BSP once again left to found the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) in 1920.

Since its founding, the Labour Party has therefore always been a party of imperialism and the labour aristocracy, and any “socialism” during its founding years was that of the reformist social democrats affiliated to the Second International. These were the socialists loathed by Marx, Engels, and Lenin, who refused to support a revolutionary uprising against capitalism, and betrayed the workers by demanding that they channel their frustrations through the bourgeois parliamentary apparatus that was designed to oppress them.

Despite occasional anti-capitalist and pro-socialist rhetoric, the Labour Party has never sought socialist advance. The “post-war consensus” between the capitalist and working class under Clement Attlee after WWII is often romanticised as an example of progressive social democracy or even socialism in practice, with the establishment of the NHS and improvements in worker living standards, but this must be contextualised as a right-wing alternative to the genuine possibility of socialist revolution.

After WWII, the Soviet Red Army was world-renowned for its defeat of fascism, the socialist revolution had spread to one third of the globe, and the Communist Party in Britain was at the peak of its strength, with 56,000 members promoting a Bolshevik-style uprising on British soil. In this context, a post-war boom in capitalist profits coupled with imperialist plunder in countries like Malaya and the Gold Coast meant that some socialist-style concessions (such as universal employment and healthcare) were offered by the state-capitalist government on a temporary basis while capitalist profits continued to rise. Of course, the capitalist class was well aware that this would confuse and divide the workers’ movement by building support for reformist politics under capitalism instead of taking power through a revolutionary break. The capitalists were also safe in the knowledge that any concessions could simply be taken away again, and this is exactly what happened in the following years.

The Labour Party and the Communist Party

In Britain, the relationship between the Communist and Labour Parties has gone through several changes. At its founding, the various predecessors of the CPGB struggled to reconcile their differences over the question of seeking Labour Party affiliation, with groups like Willie Gallacher’s Communist Labour Party and Sylvia Pankhurst’s Workers’ Socialist Federation being two of the most hostile to what they viewed as counterrevolutionary reformism and parliamentarism.

In “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder, Lenin directly addressed these concerns and outlined a preliminary strategy for British communists of seeking Labour Party affiliation and standing in elections, not as a reformist strategy of securing power, but as an agitational technique for the long-term goal of overthrowing both these bodies through a Soviet-style uprising. If paired with criticism and exposure of the Labour Party and reformism, seeking affiliation at a time when the Labour Party still enjoyed mass support among the working class was an effective way to expose Labour Party betrayal and its true class interests, thereby drawing the working class out of its influence. This was a strategy summarised by Lenin:

“At present, British Communists very often find it hard even to approach the masses, and even to get a hearing from them. If I come out as a Communist and call upon them to vote for Henderson and against Lloyd George, they will certainly give me a hearing. And I shall be able to explain in a popular manner, not only why the Soviets are better than a parliament and why the dictatorship of the proletariat is better than the dictatorship of Churchill (disguised with the signboard of bourgeois “democracy”), but also that, with my vote, I want to support Henderson in the same way as the rope supports a hanged man—that the impending establishment of a government of the Hendersons will prove that I am right, will bring the masses over to my side, and will hasten the political death of the Hendersons and the Snowdens just as was the case with their kindred spirits in Russia and Germany.”

This strategy certainly had the potential to be successful in the early days of the Labour Party, with each successive Labour government disappointing the workers and bringing more of them over towards the communist cause, and the CPGB continued to seek Labour Party affiliation right up to the 1950s. However, the Soviet leadership later became critical of what they viewed as reformist “lesser-evil” politics among the ranks of Britain’s communists, particularly following the dissolution of the Comintern and the aftermath of the Second World War. When in 1950, the CPGB was ready to create a new long-term programme with the support of the Soviet Union, Stalin had this to say to the General Secretary Harry Pollitt in the minutes of an in-person meeting in Moscow:

“Comrade Stalin states that as he thinks, the Communist Party of [Great Britain] takes a very soft and completely unprincipled position in the struggle against the Labour Party. The [British] Communists should have told the Labourites that they, the Labourites, are not at all Socialist but the left wing of the Conservative Party. This is not done. This needs to be openly pronounced. [British] Communists must state that under the Labour government the capitalists feel very fine, that their profits grow. This one fact speaks out that the Labourites are building no socialism.

Comrade Stalin further states that, in the [1951] election the defeat of the Labour Party should certainly not be permitted, but one should criticise the Labour Party from the principles of socialism. Such criticism impresses the workers as the workers see that nationalisation brought about by the Labourites does not give them, the workers, any benefits and, on the contrary, secures for the capitalists all sorts of profits. It does not happen that the profits of capitalists grow and at the same time the conditions of the working class also improve. If the profits grow then the condition of the workers does not improve but goes down. This is how we, the Soviet people, understand this and the British workers shall also understand such agitation.”

This re-affirmation that both Labour and the Conservatives stood against the workers and that it was the Communist Party’s role to expose the sham of social democracy was included in Harry Pollitt’s introduction to the British Road to Socialism in 1951: “The dominant Labour Party leaders, Attlee, Bevin and Morrison—like MacDonald, Snowden and Thomas before them—have nothing in common with Socialism or the interests of the working people. Their outlook and practice reflects that of the Tories and the wealthy ruling class whose interests they serve, and not the aims of the working people. They are in reality only a left-wing of the Tories, like the old Liberal Party.”

Nevertheless, the first British Road to Socialism still represented a significant shift in line away from the previous programme, For Soviet Britain, mainly due to supporting the parliamentary apparatus instead of its replacement with soviet-style councils. There has since been heated debate over the extent to which Stalin endorsed or even facilitated this change among supporters and opponents of both Stalin and the BRS.

It is undeniable that Stalin explicitly opposed the reformist path to socialism throughout his life, but minutes from his meeting with Pollitt in 1951, as well as from a meeting with a Labour Party delegation to the Soviet Union in 1946, indicate a change in perspective on the relationship between the CPSU and the communist parties in the imperialist countries, as well as on the role of parliament in Britain’s socialist transition.

To Pollitt, for example, he refers to the People’s Democracies of Eastern Europe and elsewhere which kept parliamentary forms of government, but were still the product of armed revolution, potentially indicating support for a similar pathway in Britain. On the other hand, his conciliatory tone towards the Labour delegation was likely due to a desire to extend the united front period beyond WWII at a time when the Soviet Union had been devastated by the war and was in desperate need of time to rebuild. This led to efforts to reassure Clement Attlee’s social-democratic government that a Bolshevik-style uprising in Britain was not currently on the cards, instead preferring to emphasise the commonalities between their two distinct brands of “socialism.”

In either case, support for the parliamentary road became the explicit position of the Soviet Union following Stalin’s death when Khrushchev announced at the Twentieth Congress of the CPSU that the strength of socialism throughout the world had opened the door to “peaceful transitions” to socialism, including through elections through bourgeois parliaments. This then influenced the political programmes of communists in Britain, the United States, Australia, and elsewhere.

The Labour Party Today

Today, the Labour Party has a mixed class base, but it is overwhelmingly dominated by the most reactionary sections of the “middle classes” and upper strata of the working class, with significant capitalist backing. This is typified by the likes of former state prosecutor, Keir Starmer, and the current Labour cabinet at time of writing contains only one person who is not from the stratum of professionals and managers (Angela Rayner), while manual workers are almost completely excluded. It also has the support of working-class traitors and collaborators represented by its backers in the trade union leadership. Other “controlled opposition” figures like Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn have also represented an upper stratum of the workers, one with some philanthropic sympathy towards the plight of the working class, but without the capacity for revolutionary leadership.

Many trade union leaders have supported lobbying the Labour Party through affiliation fees and campaign support to slow the decline of working-class living standards in Britain. However, this reformist strategy was set up to fail, as capitalist interests have inevitably succeeded in outspending the trade unions, now representing a larger source of Labour Party funding for the first time. At the same time, opposition to militancy and strike action has disarmed the workers of their only two advantages and reliable sources of leverage against the capitalists and politicians.

Many amongst Labour’s wider politicians and membership call for worker concessions in Britain, but always from within—and benefiting from— the continued existence of capitalist imperialism and its brutal consequences abroad. The great uproar from the right of Labour when party leader Jeremy Corbyn made calls for disaffiliation from NATO shows where the wider party structure’s true interests lie, and whether through personal weakness or pressure from imperialist interests, Corbyn soon dropped this demand from Labour’s manifesto, effectively accepting cooperation with US imperialism as a prerequisite for any domestic, pro-worker reforms.

This and other such concessions showed that Jeremy Corbyn never represented a threat to capitalism or imperialism, and his detachment from the more revolutionary strata of the working class resulted in foolhardy betrayals of the workers, such as through opposition to the Brexit referendum which secured exit from the imperialist and anti-worker European Union. This alienated the working class and was the primary reason for his defeat in 2019, although the minimal social reforms which he did promote were enough to attract claims of antisemitism backed by the Israel lobby from both the Tories, his own party members, and the bourgeois media. This, despite Corbyn’s long-standing record of supporting peace in places like Palestine.

With Corbyn’s electoral defeat in 2019, an emboldened liberal centre in the Labour Party has worked to root out any trace of social democracy from its ranks. The 2024 election saw Labour lose half a million votes, yet return a huge majority under the bourgeois parliamentary dictatorship. This was with a mandate from only 20% of the population, primarily from among the “middle” classes and upper strata of the workers. Meanwhile, of those workers who do still participate in this rigged electoral system, many are abandoning Labour for the unapologetically “anti-establishment” parties of both the left and the right who have been the most vocally critical of Labour Party liberalism. To some, this is cause for concern, but others recognise the fertile ground for spreading revolutionary politics among their ranks.

To date, Labour has continued most Tory policies on behalf of British capital, and the response to recent votes at time of writing in support of the child benefit cap and against Winter Fuel Payments have shown that even the mildest social democrats face suspension. Meanwhile, anti-imperialists are largely non-existent, with both the left and right of Labour broadly united in supporting arms to the United States’ proxy war in Ukraine, and shedding crocodile tears for Palestine without any material support for the resistance. But kicking out its social democrats may well be Labour’s undoing, as a controlled left opposition has historically always been a key barrier to building an independent political opposition of the working class, which needs its own vanguard party. We cannot simply make up a faction or network within a party like Labour.

Marxist-Leninists must therefore come together as a Communist Party and build up a working-class movement outside of the parliament-centric reformists. It is necessary to build up structures of working-class democracy that can stand on their own two feet and that do not rely on the resources of a Labour Party that can easily co-opt or crush internal opposition. By building favour for a communist programme, by developing independent, democratic structures of working-class power, and by exposing the errors and betrayals of social democracy and Labour imperialism, we can win the sympathies of workers who have been conditioned, as much by the Labourites as by Thatcher, to believe that There Is No Alternative to capitalism and its parties.

As an independent communist party, we must openly declare our ideals without impediment, to show that it is a communist strategy and communist methods that will effectively serve the mass of the working class, and build up a movement that is not tied myopically to general election cycles. Any worker concessions that a Labour Party or any other government does enact must therefore only serve as a means to an end: to build towards communist revolution.

Further Reading:

Labour: A Party Fit for Imperialism, R. Clough

For Soviet Britain, Communist Party of Great Britain

The British Road to Socialism (1951), Communist Party of Great Britain

“Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder, V. Lenin

Debates in Britain on Liberal Labour Policy, V. Lenin

On the British Road to Socialism, J. Stalin

Record of the meeting between the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, I.V. Stalin, and members of the delegation of the Labour Party of Great Britain, 7 August 1946, J. Stalin

Discussion Questions:

- Why was Jeremy Corbyn’s social democratic project never going to succeed? If he had somehow won a general election, what would have happened?

- Why did Lenin promote affiliation to the Labour Party? Would he propose the same strategy today? Why/why not?

- Compare the “For Soviet Britain” and “Britain’s Road to Socialism” strategies. What are the main differences?

- Is it possible to compromise with imperialism and anti-communism by uniting with the left of the Labour Party? Why/why not?

- What can we do to expose the Labour Party as an anti-communist institution and encourage workers to join the communists instead?