Humanity is at the precipice of a very serious ecological crisis. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution all threaten the stability of human society. However, despite the vast evidence, countless international summits, and increasing public concern, still no meaningful action is being taken by most governments.

For Marxist-Leninists, to address the environmental crisis we must understand the underlying economic system. After all, this determines which class has the power to decide whether a forest is bulldozed, oceans polluted, or soils poisoned.

The environmental crisis, far from being an inevitable result of human activity, is the product of a historically specific economic system: capitalism. Under capitalism, labour, supplied by the working class who own nothing but their ability to work, transforms nature into commodities which are sold on a market for profit. From this process, capitalists extract surplus value which is used to continue and further expand production. Competition between capitalists compels them to expand and intensify production, cut costs, gain ever greater access to raw materials, and find new markets or expand existing ones.

This dynamic of accumulation determines how society produces, distributes, and consumes commodities. This takes precedence over any other consideration, including the environment. The logic of capitalism turns nature from a living, complex, and delicate system into a simple source of raw materials and a dump for waste products. As Engels identified in Dialectics of Nature: “As individual capitalists are engaged in production and exchange for the sake of the immediate profit, only the nearest, most immediate results must first be taken into account.”

The drive for accumulation underlies the irrational and environmentally destructive features of capitalist society such as planned obsolescence and inefficient and unsustainable forms of transport and farming. Capitalists are incentivised to exploit this free source of profit, and those that don’t are punished and outcompeted. The drive to cut costs also turns nature into a dump. Beaches and oceans across the globe are polluted with plastic and waste from commodities designed to break or be thrown away. Economies kept dependent on oil pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere while the fossil fuel giants make record profits. The recent scandal of water companies releasing sewage into British waterways is the result of the companies preferring to shoulder meagre fines rather than invest in adequate processing facilities.

The capitalist class benefit from unbridled access to the earth’s land and resources, extracting vast profits while working-class people deal with the environmental consequences. Capitalists “privatise the wealth and socialise the poverty” in the words of former Bolivian president, Evo Morales.

Perpetual expansion of production is bound to come into contradiction with a finite planet. As natural resources and rates of natural processes are limited, the capitalist drive to produce more commodities at an ever-increasing rate runs up against natural limits. However, as producing and consuming in a rational and sustainable way is at odds with the logic of capitalism, new technologies are instead used to overcome natural limits. For example, as soil is degraded from intensive farming, ever greater amounts of artificial fertilisers are applied which sacrifice long-term sustainability for short-term profits. Rather than reducing greenhouse gas emissions, capitalists propose deploying carbon capture technology to remove carbon from the atmosphere, allowing fossil fuel-based accumulation to continue uninterrupted. This allows business as usual to continue while also opening further avenues for investment.

These quick fixes are not sustainable. As Engels remarked: “Let us not, however, flatter ourselves overmuch on account of our human conquest over nature. For each such conquest takes its revenge on us. Each of them, it is true, has in the first place the consequences on which we counted, but in the second and third places it has quite different, unforeseen effects which only too often cancel out the first.” We are now seeing the “unforeseen effects” of unbridled accumulation in potential runaway global warming, frequent extreme weather events, and widespread crop failures.

Through imperialism, the capitalist class of the imperialist countries super-exploit the land, labour, and resources of the Global South, exporting environmental destruction in the process. The militarism and wars driven by imperialism also have a catastrophic impact on the environment. The U.S. military is the world’s single largest institutional producer of fossil fuels, emitting more greenhouse gases than countries such as Sweden, Hungary, and Finland. The UK’s defence sector also accounts for 50% of the government’s greenhouse gas emissions.

As the public becomes more concerned with the state of the environment, capitalists attempt to mislead them into thinking that meaningful action is being taken through “greenwashing”. This often takes the form of falsely claiming to be on track to meet environmental targets, applying intentionally misleading “eco-friendly” labels to products, or exaggerating the impact of minor changes to their materials or operations. The capitalist class also works hard to moralise against the consumer, obscuring the capitalist basis for environmental degradation and blaming individuals. Simultaneously, the capitalist class fund and platform countless pseudoscientists and organisations that spread misinformation about the existence or cause of the environmental crisis. Marxism is only valuable so long as it remains scientific, so it is important for socialists to promote a class-based understanding of the roots of this problem and socialist solutions to combat capitalist misinformation.

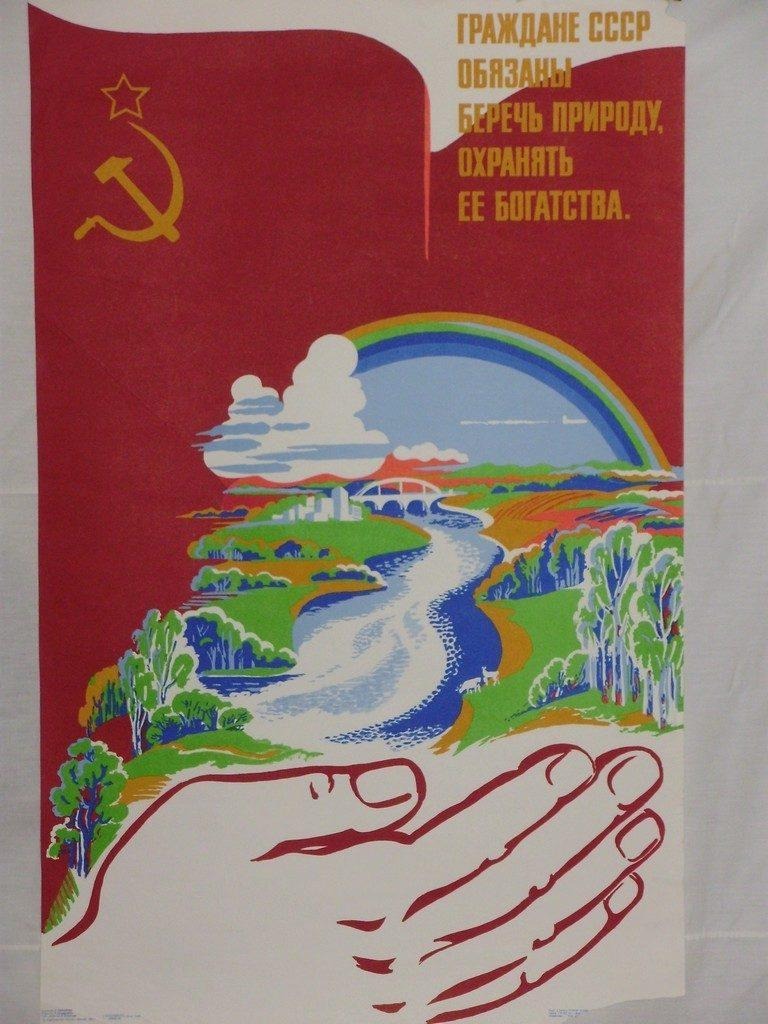

In contrast to capitalist economies, existing socialist states today demonstrate what can be achieved in environmental protection with a socialist economy. For example, Cuba is world-leading in sustainable agriculture, producing food while minimising use of environmentally harmful chemicals. The government is also implementing measures to restore mangrove forests and coral reefs, both important habitats for buffering the effects of storms on coastal communities. The Caribbean nation has also implemented a 100-year climate change plan to mobilise society to prepare for the climatological impacts over the next century, and even provides free housing to Cubans who have lost their homes due to rising sea levels. This is unheard of in capitalist countries where people are forced to bear the brunt of climate change as individuals. According to the World Wildlife Fund, Cuba is now the most sustainably developed country in the world.

Contrary to anti-communist propaganda, China is a very modest polluter in proportion to its size and scale of development, with per-capita carbon emissions being comparable to other developing countries like Libya. China is also world-leading on environmental issues in terms of its rate of improvement, promoting a transition to what it calls an “ecological civilisation” and promoting environmentally sustainable economic development under the slogan of “clear waters and green mountains are as valuable as gold and silver mountains.” Reforestation efforts have doubled forest cover between 1980 and 2020. While reducing its reliance on coal, each year China dwarfs other countries in renewable energy installations, and is projected to surpass its 2030 target for solar and wind capacity five years ahead of schedule. By building extensive high speed rail networks and boasting around 98% of the world’s electric buses, China is also making important progress in decarbonising and electrifying its transport.

What can be done here in Britain? Major sections of the environmental movement today base themselves in liberal and anarchist environmentalism, prioritising divisive stunts, disruptions, or individual lifestyle changes. This may be because climate change is a long-term problem, meaning it primarily draws in the “middle” strata who are less concerned with more immediate crises such as cost of living or unemployment and lack a class-based analysis of the issue, causing these activists to fail to target the system and class responsible. At best, their strategy is ineffective. At worst, it alienates the masses of working-class people who will bear the cost of capitalism’s environmental crisis and can be the only class to lead such a profound economic transformation. Green capitalism is not an option, meaning that any proposal for a transition must champion working-class demands first and foremost.

Acknowledgement of the climate crisis can cause anxiety and despair, but identifying that the problem lies in the capitalist economic system also accelerates movements to overthrow it. Only a revolutionary and socialist environmental movement led by the working class which prioritises employment, work, and living conditions in any economic transition can transform our relationship with nature for the better, strengthen our co-operation with the working classes throughout the world, and develop our productive forces to the point where we are capable of defending ourselves against crisis. In the words of Brazilian trade union leader and environmentalist Chico Mendes: “Ecology without class struggle is gardening”. It is the responsibility of communists to carry this understanding into the labour movement and build a revolutionary force capable of carrying humanity forwards.

Further Reading:

Socialist States and the Environment, S. Engel-Di Mauro

Dialectics of Nature, F. Engels

The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man, F. Engels

Cuba’s Life Task: Combatting Climate Change (Documentary), Dani Films

Discussion Questions:

- Britain is no longer a manufacturing economy and has moved away from industries such as coal mining, but to what extent did this actually reduce carbon emissions globally? What was the impact on workers during this transition?

- The re-industrialisation of Britain would rebuild our manufacturing sector, as well as what has typically been the most revolutionary stratum of the working class (productive workers). Is there a conflict between this demand and the demand for a sustainable economy?

- Why is green capitalism not possible?

- Why must an environmental transition be led by the working class? What does this mean in practice?

- What has been the impact of liberal and anarchist environmentalism on working-class attitudes to the problem? How should communists respond?