The Cumbernauld Centre

Built from 1963, the Cumbernauld Centre has been decried for its “ugliness” and described as part of the “crap town” character of Cumbernauld by some. Little known is its connection to the Japanese architectural movement of Metabolism, and through that, its links to Marxist art forms.

Ultimately, the ideal of a town centre that would incorporate a shopping mall, a bus station, housing, and be adaptable in the same sense as a living organism to incorporate future needs crumbled under the whims of property developers with no respect for its vision, first adding and then cutting away at the building, leaving it to its current fate with North Lanarkshire Council agreeing to plans for its demolition in 2022. But what was that vision, and how does it connect us in Scotland to the socialist world?

Introduction to Metabolism

The Metabolist movement emerged in the year 1960 with the publication of the book METABOLISM/1960 – The Proposals for New Urbanism, which included works from Noboru Kawazoe, Kenzō Tange, and Kiyonori Kikutake. The Metabolist movement was explicitly Marxist in nature, with Kikutake taking inspiration from the Marxist physicist Taketani Mitsuo when Kikutake created his concept of a three-step methodology comprising ka (creation of vision through social needs), kata (prototype construed from systematic application of technology), and katachi (a resultant beautiful form),[1] a process that we can clearly understand as a reinterpretation of Hegelian dialectics and the concept of synthesis. Additionally, many Metabolists drew their heritage from or were part of the Gokikai organisation, whose members could be divided into fellow travellers seeking to create a form of people’s architecture, and others who followed international modernism in emphasising the individuality of architects.[2] In fact, the name Metabolism was coined by Kawazoe drawing upon Marx and Engels through the concept of “regeneration” from Engel’s Dialectics of Nature, translated into Japanese as shinchintaisha.[3]

Furthermore, some such as Arata Isozaki and some friends of Tange were close to the Communist Party or had been members of the Communist Party,[4] and Toshiko Kato claimed that many Japanese architects in the postwar reconstruction era were members of the left with some even having problems traveling to the United States as a result.[5] Additionally, in response to a question regarding links between Metabolism and Yukio Mishima, Kawazoe simply stated that “I don’t think there was any influence at all.”[6] Kawazoe also outright called Metabolism “our own particular brand of Marxism.”[7] In fact, Kawazoe was credited by Kikutake for being one of the main instigators of the Metabolist movement, a result of Kawazoe lending Kikutake a copy of Taketani’s book Benshoho no shomondai (“Problems of dialectics”) that would inform the process of ka, kata, and katachi.[8]

Nevertheless, the limits of the influence of Marxism on the Metabolists must be understood as well, with Kisho Kurokawa claiming in an interview that there was no Marxist component in Metabolism,[9] and Kikutake stating that he “never thought communism would succeed.”[10] Kurokawa in particular is interesting as he drew upon the tradition of revolutionary Russian avant-garde artists including Leonidov, Tatlin, and Mayakovsky, but on the other hand outright criticised Socialist Realism on Soviet television, claiming that it was a direct copy of imperial styles.[11]

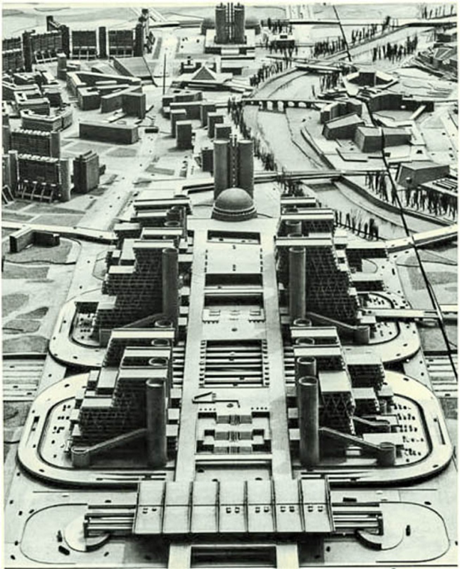

Metabolism in Skopje

Further delving into its Marxist roots, Metabolism also had a material presence in a socialist state, namely Yugoslavia. Following the widespread destruction of the 1963 earthquake, a team led by Tange created a radical plan for a Metabolist rebuilding of Skopje, although ultimately only select aspects were built such as the railway station, post office, and a number of residential blocks.[12] Sohei Imamura goes so far as to say that the reason Tange was able to execute even a small part of this master plan was the fact that Yugoslavia was a socialist state, asserting that “American-style individualism meant that the prospect of realising a comprehensive plan was precisely nil.”[13]

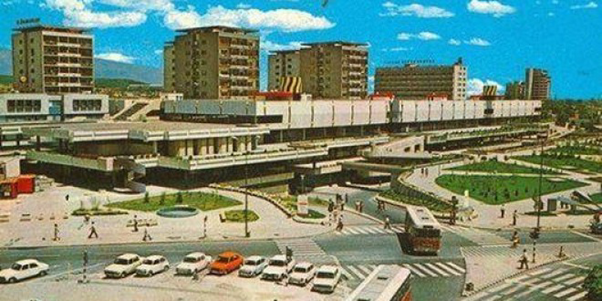

Of particular interest, especially linking back to our starting point in Cumbernauld, is the Skopje City Trade Centre, which was designed to serve as Skopje’s commercial centre but also incorporated five apartment buildings and terminated in a small park, creating a mixed-use area and allowing for ample natural light through its glass-covered atriums. From this case study, we can see that when implemented as planned, and not defiled by the mutilations of opportunistic property developers, Metabolism works in practice and can create wonderful spaces for citizens in a socialist society.

In addition, the example of Metabolism being implemented in the reconstruction of Skopje also shows the importance of internationalism in socialism, with solidarity connecting socialists around the world in material ways.

The Yugoslav pavilion at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal and its continued use as the Seaman’s Museum

From the beginning of our journey in North Lanarkshire, to Japan, to Yugoslavia, we now return back to the capitalist Western world. For the Yugoslav pavilion at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal, 28-year-old architect-school graduate Miroslav Pešić offered a prismatic design with no ornamentation and only a handful of burnt-orange panels to bring some colour in. With Pešić winning the competition, runner-up Vjenceslav Richter was assigned to its interior design, and the two were able to work together successfully in delivering the project. Although meant to be temporary, Newfoundland & Labrador provincial assembly member Hickman led an effort to acquire the pavilion, and in 1968 after the end of the World Expo the pavilion was moved to Grand Bank (Hickman’s hometown) in Newfoundland to serve as the Southern Newfoundland Fishermen’s Center, where it still stands (with the updated title of the Seaman’s Museum).

Although not specifically a building representing Metabolism, the former Yugoslav pavilion acts as a symbol of the wide and lasting influence of socialist architecture. Additionally, whilst we may often think of socialist architecture outside of the former socialist world in the form of buildings constructed in solidarity in the Global South, the former Yugoslav pavilion is particularly interesting in that it is an example in the capitalist West.

Afterword

Presenting some final thoughts and returning back to Scotland, let us consider the following points. As seen in Skopje’s City Trade Centre and its direct parallels with the Cumbernauld Centre, Metabolism could have worked in Scotland as evidenced by the fact that it has worked elsewhere. Although the case study of this investigation, Metabolism is by no means the only connection that art in Scotland, and more broadly Britain, has with socialist thinking. One needs only look to the Arts and Crafts Movement, championed by the likes of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and William Morris, and its connections to the Art Nouveau movement, Cedric Price’s design for the Fun Palace for Joan Littlewood,[14] or the Riverside Museum designed by Zaha Hadid, who early in her career keenly adopted and built on Constructivist principles. All art is political in that it was created in its political and material context, but not always connected in the ways that we think.

Questions

What other examples of socialist art can comrades think of which have had a wider impact outside the socialist world? What is this impact?

What examples of socialist or workers’ art can comrades think of from Scotland and the rest of Britain? How can other art movements be connected to socialist thinking?

How can we develop our own socialist art? (Think about pamphlets, books, and other publications released by our own Party)

Ethan Chan is a member of the Young Communist League’s Glasgow branch

Bibliography

Beanland, Christopher. Unbuilt: Radical visions of a future that never arrived. London: B.T. Batsford, 2021.

Davis, Robert. “L’Architecture of Lanarkshire.” The Critic, July 3, 2022, https://thecritic.co.uk/larchitecture-of-lanarkshire/.

Imamura, Souhei. “The Theory of Kikutake Kiyonori: A City on the Ocean.” In Metabolism, the City of the Future: Dreams and Visions of Reconstruction in Postwar and Present-Day Japan, edited by Hirose Mami, Sasaki Hitomi, Maeda Naotake, et al. Translated by Edan Korkill, Jamie Sanderson, Julian Worrall, et al, 250-254. Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011.

Jamieson, Teddie. “Cumbernauld: ‘A terrible mistake’ says architecture expert Owen Hatherley,” The Herald, April 3, 2022, https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/20026528.cumbernauld-a-terrible-mistake-says-architecture-expert-owen-hatherley/.

Koolhaas, Rem and Hans Ulbrich Obrist. Project Japan: Metabolism Talks…. Cologne: Taschen, 2011.

Mami, Hirose, Sasaki Hitomi, Maeda Naotake, et al, eds. Metabolism, the City of the Future: Dreams and Visions of Reconstruction in Postwar and Present-Day Japan. Translated by Edan Korkill, Jamie Sanderson, Julian Worrall, et al. Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011.

Naohiko, Hino. “Ruptures in Concepts of Urbanity: As Discerned in Urban Projects of the 1960s.” In Metabolism, the City of the Future: Dreams and Visions of Reconstruction in Postwar and Present-Day Japan, edited by Hirose Mami, Sasaki Hitomi, Maeda Naotake, et al. Translated by Edan Korkill, Jamie Sanderson, Julian Worrall, et al, 278-282. Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011.

Niebyl, Donald. “The History of Yugoslavia’s Pavilion at Montreal’s 1967 World EXPO.” Spomenik Database, June 5, 2023, https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/post/the-history-of-yugoslavia-s-pavilion-at-montreal-s-1967-world-expo.

Prelikj, Kalina. “Modernist Heritage: The Global Architecture Initiative that Rebuilt Post-Earthquake Skopje.” Architizer, July 26, 2024, https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/modernist-buildings-skopje-earthquake/.

Recommended reading

Alekseyeva, Anna. Everyday Soviet Utopias: Planning, Design, and the Aesthetics of Developed Socialism. New York, NY: Routledge, 2020.

Arnot, Robert Page. William Morris: A Vindication. London: Martin Lawrence Ltd., 1934.

Forgács, Éva. “A Political Education: The Historical Legacy of the German Bauhaus and the Moscow VKhUTEMAS.” In The Responsible Object: A History of Design Ideology for the Future, edited by Marjanne van Helvert, 49-65. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2019.

Gutnov, Alexei, A. Baburov, G. Djumenton, S. Kharitonova, I. Lezava, and S. Sadovskij. The Ideal Communist City. Facsimile. Translated by Renee Neu Watkins. Edited by Ute Meta Bauer, Karin G. Oen, and Pelin Tan. Boston, MA: i press incorporated, 1971; Singapore: NTU Centre for Contemporary Arts Singapore, 2022.

Jenkins, J. R. Picturing Socialism: Public Art and Design in East Germany. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2021.

Katz, Philip. Thinking Hands – the power of labour in William Morris. London: Hetherington Press, 2005.

Lifshitz, Mikhail. The Crisis of Ugliness: From Cubism to Pop-Art. Edited by David Riff. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2019.

Maleschka, Martin. Baubezogene Kunst DDR: Kunst im öffentlichen Raum 1950 bis 1990. Berlin: Dom Publishers, 2022.

Miller, Elizabeth Carolyn. “William Morris, Arts and Crafts, and the Idea of Eco-Socialist Design.” In The Responsible Object: A History of Design Ideology for the Future, edited by Marjanne van Helvert, 29-48. Amsterdam: Valiz, 2019.

Quille, Mike, ed. Class and Culture: Provocations for Cultural Democracy. London: Communist Party of Britain, 2023.

Stanek, Łukasz. Architecture in Global Socialism: Eastern Europe, West Africa, and the Middle East in the Cold War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020. Zarecor, Kimberly Elman. Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity: Housing in Czechoslovakia, 1945-1960. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2011.

[1] Souhei Imamura, “The Theory of Kikutake Kiyonori: A City on the Ocean,” in Metabolism, the City of the Future: Dreams and Visions of Reconstruction in Postwar and Present-Day Japan, ed. Hirose Mami et al, trans. Edan Korkill et al, (Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011), 250-251.

[2] Hino Naohiko, “Ruptures in Concepts of Urbanity: As Discerned in Urban Projects of the 1960s,” in Metabolism, the City of the Future: Dreams and Visions of Reconstruction in Postwar and Present-Day Japan, ed. Hirose Mami et al, trans. Edan Korkill et al, (Tokyo: Mori Art Museum, 2011), 278.

[3] Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulbrich Obrist, Project Japan: Metabolism Talks… (Cologne: Taschen, 2011), 235.

[4] Ibid, 47.

[5] Ibid, 87.

[6] Ibid, 227.

[7] Ibid, 229.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid, 377.

[10] Ibid, 135.

[11] Ibid, 377.

[12] Christopher Beanland, Unbuilt: Radical visions of a future that never arrived (London: B.T. Batsford, 2021), 178.

[13] Imamura, “The Theory of Kikutake Kiyonori,” 254.

[14] Beanland, Unbuilt: Radical visions, 93.