By 1950, the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was nearing a crossroads. After 30 years and two world wars, socialism had gone from being a word in a manifesto to a real system being built across one third of the globe. National liberation struggles were breaking the chains of empire link by link, and the coming Cold War indicated a deep anxiety from the ruling classes in the West at the thought of Bolshevik-style revolutions on their own soil.

In the 1945 General Election, the working classes of Britain showed a deep hunger for change, not only by changing the ruling-class guard from Churchill’s Tories to Clement Attlee’s Labourites, but also by carrying two communist MPs, Willie Gallacher and Phil Piratin, into the bourgeois parliament at the heart of empire. With universal employment, housing, healthcare, and education being rolled out in East Germany and beyond, and a great admiration for “Uncle Joe” Stalin following the Red Army’s resounding defeat of fascism in Europe, Clement Attlee had the task of convincing British workers that real change did not come from revolution, but from capitalist reforms through parliament.

And so, a post-war boom in the British economy combined with the profits of empire and the ideological need for a pro-capitalist alternative to socialism to allow for a fleeting moment of class collaboration, known as the “post-war consensus”. Intensified imperialist violence and theft from British colonies like Malaya and the Gold Coast secured rising profits for the capitalists, while Keynesian social democracy redistributed scraps from the table to the working class. The lion’s share went to the labour aristocracy: the trade union leadership and the managerial class, breeding within them a vested interest in imperialist projects, but even the broad masses of the workers experienced tangible improvements to their lives, including the right to employment and a national health service.

Although heralded by reformists as an example of Labour Party “socialism”, compared with the revolutionary alternative just a few hundred miles east, it was transparently a right-wing programme which, thanks to imperialist plunder, did not touch one penny of capitalist profits. And, when Attlee won the next general election 5 years later, his government was only too happy to begin dismantling the welfare state that they had just helped build—a prime example of the fleeting nature of social reforms under capitalism when faced with the relentless search for profit.

Social democracy was also having its impacts on the communist movement more broadly. The dissolution of the Communist International (Comintern) in 1943 also signalled the end of the old “Class Against Class” line which opposed any form of collaboration with pro-capitalist forces. This included the social democrats (even “left” social democrats), who had been previously denounced as the “left wing of fascism” or, in Lenin’s words, “social imperialists” for delivering social reforms at home, but imperialism abroad. “Class Against Class” was replaced with the policy of the “United Front” between communist and anti-communist forces for the limited task of driving out fascism.

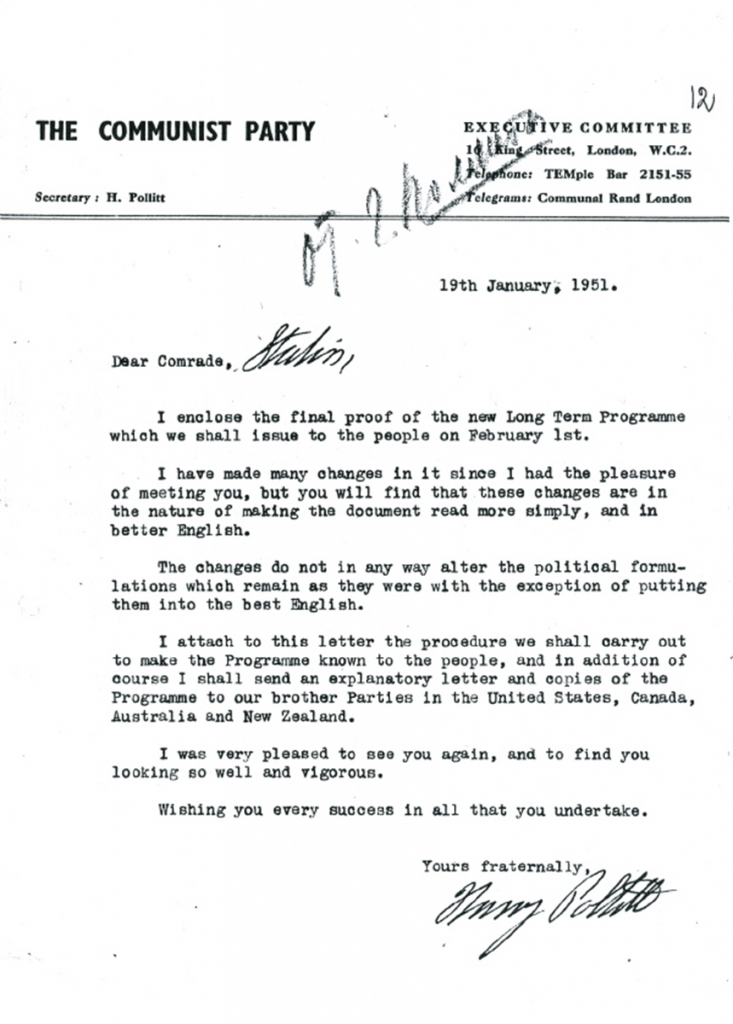

The CPGB did worse in the 1950 General Election than the previous one. Its vote count was only slightly smaller, but it lost both of its sitting MPs. According to documents from the Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History in Moscow, CPGB General Secretary Harry Pollitt reached out to Stalin around this time for guidance in the next general election, called for the following year. This led to the creation of the Party’s first long-term political programme, the British Road to Socialism. The programme replaced the CPGB’s Class Against Class and For Soviet Britain programmes that had come before it, changing, among other things, communist strategy towards the bourgeois parliament and the Labour Party. The eighth edition of Britain’s Road to Socialism is still used by the CPB today, although the original was much more influential, selling 150,000 copies in just two weeks.

The almost mythological influence of Stalin and the Bolsheviks in the creation of this document has been a key battleground over its significance. Among Marxist-Leninist critics, it is unthinkable that Stalin could have had a hand in the creation of such a programme when considering the sorry state of communism in Britain today. For its defenders, Uncle Joe’s warm nod of approval carries a weight that reverberates 70 years into the future, shielding later editions of the programme from any criticism in the present. Both these positions are forms of dogmatism, which is a significant obstacle to creating a living and evolving party that’s capable of meeting the needs of the working class in the 21st Century. Our approach to history should not be dogmatic. After all, we shouldn’t need to rely on dogma if our theories are correct. Instead, we need to study the facts and lessons of history as they stand—to shine a light on the past so that we can prepare for the future. And the facts of history state that, unless forgeries have been planted in the Russian archives (which is highly unlikely), Stalin and the Bolsheviks were not only a guiding force in the creation of communist party programmes in India and Indonesia, but also had a considerable influence here in Britain.

The Foreign Policy Commission of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) (former name of the CPSU) sent a letter to Stalin on 23 May 1950 informing him of Harry Pollitt’s request for help in creating a new Party programme for the upcoming election, advising Stalin on how to respond. According to the letter, Pollitt’s main priority was to prevent Churchill returning to power, and having assessed that the “Labourites” were less of a threat to the working class than the Tories, he was willing to make significant concessions, including:

- Significantly reducing the number of communist candidates from the 100 who ran before

- Recommending Labour candidates wherever a CPGB candidate didn’t run

- Allowing Labour leaders to run unopposed, and

- Pressuring unopposed Labour candidates from the left to support key working-class demands.

Pollitt must have felt very conflicted about these concessions considering his consistent hostility towards the Labour Party previously. In an article from ten years earlier, his most merciless attacks were on the Labour leadership, but even the Labour ‘left’ came under fire for helping to “disorganise and confuse the struggle of the membership of the Labour Party against the reformist policies of the dominant right-wing leadership.” He writes:

“If the role of the right-wing leaders has been a shameful one, that of the ‘left’ has been both shameful and pitiful, reaching its highest expression in the present combination around the Tribune, some of whom, week by week, begin to reveal a growing recognition that once again they have climbed on to the wrong band-wagon, and, as usual, backed the wrong horse.“

The Bolsheviks were very firm that this earlier position was the correct one and make it clear that the CPGB’s programme and propaganda should explicitly state that there is no substantial difference between the Conservatives and Labour. The Labour Party equally supports attacks on the working class at home and imperialism abroad, so Labour candidates should not be supported on this basis. Therefore, if they do reduce the number of candidates, they should still stand candidates in a large number of constituencies (including those of the Labour leaders), use candidates that are unlikely to win to “expose the reactionary essence of Labour politics”, and make a concerted effort to win seats in Communist strongholds.

The only electoral pact on offer should be to support Labour candidates in uncontested seats on the condition that the Labour Party supports the Communist candidates in turn. If (and when) this was rejected, the CPGB should only back Labour candidates on five conditions. Labour candidates must:

- Speak against the dangers of a new war against the Soviet Union

- Support the demand for prohibition of nuclear arms

- Declare that governments who support first use of nuclear arms are war criminals

- Support the struggle for better relations with the Soviet Union, China, and the People’s Democracies of Eastern Europe, and

- Support the struggle to improve living conditions for the working masses.

If (and when) this was rejected, the CPGB should refuse to support Labour candidates.

In either case, the Bolsheviks believed that there were much higher priorities for communists in Britain than the election itself. They urged Stalin to push for wide-scale political and organisational work among British workers to link the anti-imperialist struggle against a new war with the improvement of working-class living standards, to strengthen the struggle against reformism and social democracy, to strengthen links with trade unions, and to widen links between the Party and the masses through the Party organisations and the Party press.

In other words, communists in Britain should act as revolutionaries, not parliamentarians.

A week later, Pollitt and Stalin meet in person for the second time in their lives to discuss Harry Pollitt’s letter and the state of the class struggle in Britain, and it’s clear from the minutes that Stalin did have direct involvement in creating the new Party programme. By and large, he supported the recommendations of the Foreign Policy Commission, although he agreed with Pollitt that Churchill should not be allowed to win if possible. He admitted that the Labour Party is better, “though only a little bit better than the Conservatives”, and that the working class still incorrectly believes that Labour is their party, so this should be considered in strategy.

Stalin raised the need for the CPGB to develop a long-term programme which could provide direction to the working class beyond the next election, stating that the CPGB should use this to expose Labour policies such as “nationalisation under capitalism” as anti-socialist. His advice on the Communist Party’s relationship to Labour is very clear, and is worth copying here in full:

“Comrade Stalin states that as he thinks, the Communist Party of Great Britain takes a very soft and completely unprincipled position in the struggle against the Labour Party. The British Communists should have told the Labourites that they, the Labourites, are not at all Socialist but the left wing of the Conservative Party. This is not done. This needs to be openly pronounced. British Communists must state that under the Labour government the capitalists feel very fine, that their profits grow. This one fact speaks out that the Labourites are building no socialism.

“Comrade Stalin further states that, in the elections the defeat of the Labour Party should certainly not be permitted, but one should criticise the Labour Party from the principles of socialism. Such criticism impresses the workers as the workers see that nationalisation brought about by the Labourites does not give them, the workers, any benefits and, on the contrary, secures for the capitalists all sorts of profits. It does not happen that the profits of capitalists grow and at the same time the conditions of the working class also improve. If the profits grow then the condition of the workers does not improve but goes down. This is how we, the Soviet people, understand this and the British workers shall also understand such agitation.“

Representing the Bolshevik position, Stalin is clear that although the Labour Party does represent a “lesser evil” in this particular election, the Labour Party is fundamentally an obstacle to socialism in Britain, and criticisms of the Labour Party from the socialist position should be open, honest, and unyielding. He also recommends that the CPGB seek to break the link between the Cooperative Party and the Labour Party, recognising that communist leadership of working-class forces is blocked by Labour Party affiliation. Stalin’s final words on the Labour Party are for the communist supporters who have been kicked out. He recommends an institution of “sympathisers” for those who may not be ready to become communists themselves, but who are sympathetic to the programme and want to support. New members can later be recruited from this institution if they are considered ready.

Another, more controversial part of the discussion, indicates a profound shift in line on the role of the bourgeois parliament in Britain and other Anglo-Saxon nations:

“British Communists are accused in Britain that they have put before themselves the aim of establishing Soviet power in Britain. The British Communists must respond to this in their Programme that they do not want to weaken the Parliament, that Britain shall reach socialism through its own path and not through the path traversed by Soviet power but through a democratic republic that shall be guided not by capitalists but by representatives of peoples’ power, i.e., a coalition of workers, working intelligentsia, lower classes of the cities as well as farmers. Communists must declare that this power shall act through the Parliament.

“Comrade Stalin said that the talk should be of a Peoples’ Democratic path for the movement of Britain to Socialism and not of the Soviet path but of that path on which the countries of Peoples’ Democracy are moving towards socialism.“

The question of why Stalin encouraged this shift in position, using the example of the People’s Democracies of Europe to promote a transition to socialism through parliament, is the subject of much debate. As Marx wrote in his analysis of the Paris Commune: “the next attempt of the French Revolution will be no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, but to smash it, and this is the precondition for every real people’s revolution on the Continent.” Engels and Lenin were also clear on this subject, clarifying that a communist’s role in parliament is not to win the rigged game of bourgeois democracy, but to use the electoral struggle to educate the masses on the necessity for revolutionary violence. Stalin was well aware of this and had always supported this position, and even now expected violent struggle, clarifying in later letters to Pollitt that any “people’s parliament” would come under the most desperate attack by the bourgeoisie and should defend itself in kind.

The journal Marxism-Leninism Today presents several different interpretations as to why Stalin gave his position on the path of People’s Democracy in Britain. Prof. Vijay Singh argues that it was a correct reflection of the current state of communism in the world and the theory of People’s Democracy as developed by Georgi Dimitrov, giving examples of countries in which peaceful parliamentary struggle had supported in some way the violent revolutionary struggle which came after. Hari Kumar cites Stalin’s meetings with other communist party leaders in which he states the possibility of alternate paths to socialism than the dictatorship of the proletariat. Garbis Altinoglu argues that Stalin’s advice was likely influenced by his recognition of the relative weakness of the communist movement in Britain and the strong parliamentary illusions of the British working class, accurately identifying that both would need to be overcome before promoting armed revolution based on the establishment of workers’ councils. In any case, all three writers clarify that however Stalin’s advice or reasoning should be interpreted, there is little reason to change the Marxist-Leninist understanding of the need to smash the bourgeois state apparatus, with the People’s Democracies of Europe being born out of the Red Army’s militant struggle against fascism, not any bourgeois electoral path.

Perhaps Stalin’s shift in position towards the Anglo-Saxon nations reflected a post-war disappointment that their revolutions had still failed to materialise. With no revolutionary situation on the horizon, Stalin may have determined that the only way forward was for communists to bide their time while the global communist movement strengthened its footing and recovered after the war. Demonstrating the same realpolitik practicality of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Stalin may have been attempting to extend peace with the anti-communist forces in the dominant imperialist nations for as long as he could, publicly stating that Moscow was not involved in British affairs and that no immediate seizure of power was on the cards (as indeed, it wasn’t).

This does not mean that Stalin was naïve at the prospects for long-term peace. His response to Churchill’s Iron Curtain speech in 1946 showed that he interpreted it as a clear declaration of war, warning Britain and the imperialist camp that they would be “thrashed” if such a war came to pass, just as they were when they invaded Russia to try to crush the October Revolution. In the case of direct conflict between Britain and the Soviet Union, the “path of People’s Democracy” could therefore have been far more likely in Britain than a homegrown revolution.

Stalin makes other interesting suggestions about communist strategy in Britain. For example, British communists were often attacked as national traitors for wanting to break up the British empire. Stalin said they should respond by showing themselves to be the true patriots for wanting a new relationship with the colonies on equal footing, much like Russia’s relationship to its former colonies after the founding of the Soviet Union. Communists should state that it was in fact the Conservatives and Labour who were destroying their country by maintaining this exploitation. Stalin later calls for a similar position against subjugation by the United States, saying that the patriotic position should be to oppose US imperialism and a war with the Soviet Union, an example of the “socialist patriot” position which can prove so controversial today.

After giving his warm regards to Stalin, Pollitt then returned to England to discuss the programme with Palme Dutt and the CPGB Central Committee. What follows are several months of correspondence between Stalin and Pollitt to correct parts of the programme, and then a final, in-person sitdown on 5 January 1951.

Stalin’s final words on the document revolve around precision over word choice and policy. He opposes ultra-leftist positions, such as nationalising all landed property without compensation, recognising that this creates unnecessary enemies among small property holders during the first stage of the revolution, who should be won to the revolution through peaceful means where possible. He also argues for a “Socialist Britain and Commonwealth of Nations”, similar to Russia’s relationship with its colonies after the revolution on a united but equal footing. He also rejects the idea that all wealth and resources can be returned to the colonies, since much has already been consumed and the programme should represent what is actually possible. This mirrors contemporary Marxist criticisms of some of the theories and demands of the “decolonial” Left today.

Harry Pollitt concurred with all the suggestions, and Stalin gives his final words on the document:

“Comrade Stalin answers that the draft has been well prepared and says that the appearance of the Programme of the Communist Party of Great Britain occupies a turning point in the history of the working-class movement of the Anglo-Saxon countries. This Programme in its essence is a suitable document for the Communist Parties of USA, Canada, Australia and other Anglo-Saxon countries. The Communist Party of the USA at the moment is in a hard situation; they have a lot of confusion. One should, however, recognise, says Comrade Stalin, that however much the Americans may take pride in their democracy, in monarchist England there is more freedom than in the USA.“

The “hard situation” of the CPUSA was in reference to its recent refounding and the expulsion of former General Secretary Earl Browder, who had implemented an entirely revisionist programme of reforms and ultimately dissolved the CPUSA in 1944 in favour of creating an organisation to lobby the two-party system. Stalin offers his support in publishing the programme across the ‘Anglo-Saxon’ countries in large numbers.

So, what can we learn from this exchange? As the documents are likely genuine, Stalin did indeed play a heavy role in producing the CPGB’s British Road to Socialism. Among his major contributions, he and the rest of the Bolsheviks repeatedly demanded a stronger position against the Labour Party and unrelenting critiques to ensure that there was no confusion about their class interests or “socialist” credentials, while still conceding that a Labour government would be preferable to Churchill.

Stalin’s position on the path of “People’s Democracy” over the immediate seizure of power through British soviets may have reflected his famous realpolitik practicality, a push for peaceful redevelopment after the war in preparation for future conflicts, along with practical considerations that a revolution in Britain was not likely in the immediate future. Whatever his reasoning, he certainly doesn’t have any misconceptions about a peaceful transition to socialism and urges Pollitt to include in the programme the defence of a people’s parliament from capitalist violence as a matter of urgency.

Stalin was also a strong supporter of socialist patriotism, urging Pollitt to expose the Labour Party and the Conservatives as the true traitors of the nation for wanting to sell Britain out to the Americans, and that an anti-imperialist position towards the US and the British Empire was in Britain’s national interests. He also warns against “ultra-leftist” positions against the petit-bourgeoisie and towards Britain’s colonies, demanding that all policies were possible in practice and worked to ease the transition to socialism with as little violence as possible. Too often, we see socialists present positions that they think are most appealing to the working class or other groups over what is actually possible and preferable based on material conditions. At least in Stalin’s eyes, this was a mistake which undermined the Party’s leadership.

Ultimately, it is important not to take the positions of bygone revolutionaries as gospel. There is much to learn from history and from the communist heroes that have come before us, but we are communists of the 21st century whose focus should be on training up a new generation of leaders and theoreticians. To create a communist organisation with real revolutionary potential, we cannot satisfy ourselves with dogmatically conjuring up the ghosts of the past, but must instead apply ourselves to our studies, identify how their positions were reached, and then determine whether they are relevant today.

Eben Williams is a member of the Young Communist League’s Glasgow branch

If you would like to find out more about the period of history covered in this piece, the author has provided some additional reading:

Revolutionary Democracy, On the British Road to Socialism, Sep. 2007.

Harry Pollitt, The Communist Party and the Labour Party, Aug. 1940.

A. P. Butenko, People’s Democracy, 1979.

Karl Marx, Marx to Dr Kugelmann Concerning the Paris Commune, Apr. 1871.

Marxism-Leninism Today, Recent Writings of Revolutionary Democracy on the British Road to Socialism, Jul. 2019.

J. V. Stalin, Interview to “Pravda” Correspondent Concerning Mr. Winston Churchill’s Speech at Fulton, Mar. 1946.

Executive Committee of the Communist Party, The British Road to Socialism (First Edition), Jan. 1951