After a century of aggression and humiliation at the hands of foreign powers, China was one of the poorest countries in the world. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the conditions and living standards of the Chinese people improved at a radical pace. Inheriting a backward, semi-feudal economy of virtually no industry, the Communist Party of China (CPC) solved the titanic problems of feeding and employing the population, stabilising commodity prices, and unifying financial and productive work– in summary, performing centuries of economic development in mere decades.

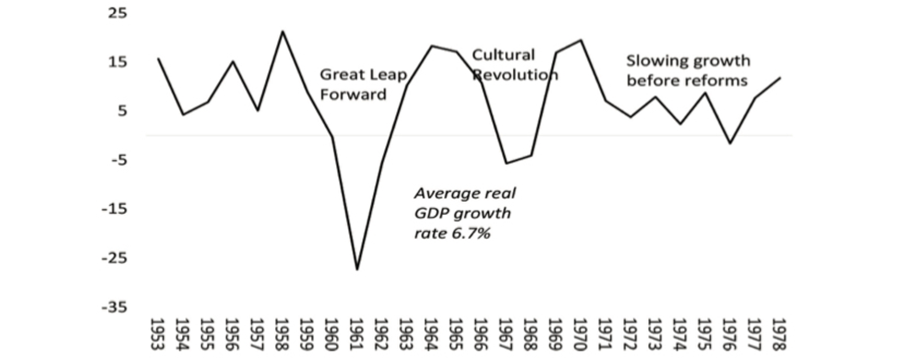

During this period, life expectancy rose by 31 years, the fastest-ever increase in a major country in human history; the average calorific intake doubled; annual income quintupled, going from 60 billion yuan to 300 billion yuan. The economy grew by 64 percent each decade, surpassing even the economic growth of the Soviet Union, which lagged behind at 54 percent. Despite this massive progress since 1949, China still faced large levels of poverty in the 1970s. Industrial expansion was waning, and these economic setbacks were further exacerbated by the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution.

The CPC determined that, in order to develop productive forces and tackle poverty, they would need to forge their own path rather than continuing to emulate the Soviet model. From 1978, they permitted the re-emergence of a small private sector and opened up to foreign investments. After these changes, China transformed from a low-income to an upper-middle income country, and since 1981, has seen 800 million people lifted out of internationally defined poverty within its borders, accounting for 75 percent of the reduction in global poverty during this period.

In the face of these staggering achievements, cynics from both the left and the right continue to misrepresent and condemn modern-day China. The purpose of this article is to address some of the major accusations, namely that China is undemocratic; an international aggressor; and, since the reforms, has ceased to be socialist.

Chinese Democracy

A common misconception amongst Western academics is the idea that China has no form of democracy. According to Stein Ringen’s book The Perfect Dictatorship: “The present Chinese regime is less strong, more dictatorial, and more of its own kind than the world has mostly wanted to believe”. He alleges that the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, has “scaled back collective leadership for a new kind of one-person rule, complete with a touch of person cult around the supreme leader.”

While Ringen is correct to call China a “dictatorship”, he is incorrect in the sense that the word is traditionally understood in the West, that is, the absolute rule of one person or a small group. The Chinese state is what Marxists refer to as a dictatorship of the proletariat: a democracy for the workers, who impose a dictatorship over the now-dispossessed exploiters. As Xi Jinping himself explains: “Whether a country is a democracy or not depends on whether its people are really the masters of the country.”

China fulfils this criterion through a Whole-Process People’s Democracy, which allows citizens to participate in the political process at all levels through a system of people’s congresses, not merely by voting in the occasional election as we do in the West. Local People’s Congresses (LPCs) exist at all levels, ranging from village to provincial, and serve as the regional organs of state power.

Made up of 2.6 million deputies representing all regions, ethnicities, and social groups, these LPCs ensure the enforcement of the Constitution, laws, and administrative regulations. They also have the authority to adopt resolutions and decide local economic, cultural, and public service development plans and budgets. The LPCs reserve the right to elect and remove governors, mayors, deputy heads, municipal district heads, alongside many other important government positions. The LPCs of ethnic autonomous areas also have the authority to formulate region-specific regulations that align with the political, economic and cultural characteristics of the ethnic groups in their area.

China’s highest governing congress is the National People’s Congress (NPC), made up of some 3,000 deputies drawn in from all backgrounds, with frontline workers and farmers accounting for 15.7% of the total, and all 56 ethnic groups represented. The primary functions of the NPC are to amend the constitution and oversee its implementation; enact and revise basic laws; appoint and remove senior officials, including the president and vice president.

Whilst the NPC serves as the decision-making body for China’s national and social development, it is not divorced from the concerns of the ordinary Chinese people. In fact, the NPC maintains a network of outreach offices operating throughout the country, ensuring the line of contact with the people is sustained at all times. As of June 2021, outreach offices have conveyed nearly 6,600 pieces of advice on 109 draft laws and legislative plans, many of which were accepted. For example, in 2015, the outreach office in Hongqiao, Shanghai received a proposal regarding the draft Anti-Domestic Violence Law, calling for community-level organizations to be able to apply for personal safety protection orders. This proposal was then accepted and became enshrined into law.

The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) is another important democratic channel, comprised of representatives from all eight democratic parties, all ethnic groups and regions, including overseas Chinese, as well as a range of people’s organisations and specially invited individuals. Through the means of CPPCC consultations, opinions on major state policies and decisions are received from people from every walk of life, enabling the various perspectives of social groups and minorities to be accounted for within state policy.

Centralisation of government in the policy-making sphere is counterbalanced by decentralisation in the work of Party cadres, which are appointed to all geographical areas and tasked with soliciting and fulfilling people’s needs. The cadres report their findings to the Party, allowing centrally determined decisions and economic plans to be consistent with the needs of society.

The NPC Outreach Offices, the CPPCC and the Party Cadres serve as communication networks linking the masses with the CPC, allowing the state to fully represent the will of the people on a national level. Simultaneously, at a regional level, the People’s Congresses uphold the practise of grassroots decision making. Clearly, claims that the Chinese system is undemocratic, or even more nonsensical, a “one-person rule”, are fundamentally incorrect.

Chinese Foreign Policy

The European People’s Party Group, the largest political group in the European Parliament, asperse that: “Beijing behaves as a global free rider, pursuing an aggressive and even hostile competition policy that ignores international rules and ruthlessly pursues its interests… [China is] threatening not only its neighbours and the rule-based global order but also our European interests and allies.” This rhetoric is commonly used to rally public opinion in favour of an aggressive European foreign policy against China.

To truly comprehend China’s foreign policy, it is necessary to grasp the concept of The Shared Future of Humanity, which takes its roots in the Marxist theory of the socialisation of labour. Numerous studies have confirmed that the production of intermediate goods, termed as “circulating capital” by Marx, is the primary factor contributing to increased productivity. Intermediate goods are produced due to a division of labour, that is, when multiple producers contribute to a final product. Thus, when labour is highly socialised, it is also highly productive.

Following this logic, a greater international socialisation of labour or, in other words – globalisation, serves to increase productivity and improve living standards for the international community as a whole. Therefore, differences between nations are not a disadvantage, as labour is more productive when it is divided, and subsequently when it is different. (For more information on this subject, see Section Four of John Ross’ book, China’s Great Road.)

Taking the vision of the Shared Future for Humanity as its guiding principle, the CPC seeks to build an international community based on greater cooperation between nations, and where differences are celebrated and used to the advantage of the international community, rather than vilified. Since 1953, Chinese foreign policy has been underpinned by Zhou Enlai’s five principles of peaceful coexistence, which are enshrined into the constitution: mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. In accordance with these principles, China has peacefully settled land boundary issues with 12 of its 14 neighbours, and established a Code of Conduct to diplomatically address disputes in the South China sea between members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

In Africa, China has funded vital infrastructure projects considered too unprofitable by Western capitalists; contributed emergency food assistance to Djibouti, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Eritrea; provided 189 million doses of vaccines to 27 countries; and waived 23 interest-free loans for 17 nations. China actively contributes to the common prosperity of developing nations through win-win investments in infrastructure projects such as the Belt and Road Initiative, with more than 150 countries and over 30 international organizations joining it in the 10 years since it was launched.

These policies stand in stark contrast to institutions like the International Monetary Fund or World Bank, which use predatory lending practices to impose US economic interests on emerging economies, keeping them indebted and demanding the adoption of neoliberal austerity as a condition for loans.

So, if China is not imposing herself on other nations through economic domination, but rather championing economic cooperation, perhaps the EPP Group are alluding to a a serious military threat that China represents? Whilst it is true that China maintains one oversees military base in Djibouti, primarily to safeguard trade routes against piracy, the US has 750 overseas military bases across more than 80 countries, whilst Britain has 145 across 42 countries. The US and Britain continue to build up their military encirclement of China, with the US maintaining 313 military bases in East Asia alone, and Britain maintaining bases in Singapore, Brunei, Australia, Nepal and Afghanistan.

Additionally, whilst China favours diplomatic discussions over military confrontation when addressing disputes and concerns, the West addresses disagreements through destructive and deadly military interventions, often on the false pretence of “human rights abuses”. Even today, no senior US officials have been held accountable for crimes against humanity in Iraq including the unlawful detention, torture and indiscriminate killing of civilians. Clearly, the accusation that China is an international aggressor, made by Western officials and political groups, exposes a glaring hypocrisy.

Has China turned away from socialism?

Since Reform and Opening Up, the socialist nature of China’s economy has been questioned, with many anti-socialist pundits wrongfully attributing its success to capitalism, distorting the structure and essence of China’s Political Economy. This was expressed back in 1999 by the Japan Research Institute: “If we accept the view that the state-owned enterprises are the cornerstone of the socialist economy, then we can conclude that contemporary China has already lost its socialist mainstay”, pointing to the reduction in the market-share of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) since the period of reform and opening up to indicate this point. This argument was reiterated in a more recent Forbes article: “China’s success provides clear evidence of the power of capitalism”.

The fact remains that SOEs have not ‘melted away’ but remain a cornerstone of the Chinese economy. As of 2021, SOEs and their combined assets constituted nearly 70 percent of China’s GDP– a hardly insignificant percentage. It is indisputable that the state-owned sector occupies the leading role within the economy.

In early-20th-century China, the national bourgeoisie not only played a crucial role in the movement against imperialism, feudalism and bureaucratic capitalism but also became actively involved in the economic reconstruction of China. In 1949, the policy was adopted to encourage and assist “the active operation of all private economic enterprises beneficial to the national welfare and the people’s livelihood and shall assist in their development.” At the same time, the state-owned economy retained the leading role, making it impossible for the national bourgeoisie to lead China towards capitalism. This approach was taken in respect to Mao Zedong’s distinction between the expropriation of the bourgeoisie’s economic capital and political capital. The latter should be carried out to the end, while the former, if not contained within clear limits, risks undermining the development of the productive forces. If the bourgeoisie’s economic capital can serve the development of the economy, and thus the cause of socialism, its total expropriation is unnecessary. Evidently, the approach of enabling a private economy to exist under the leadership of a state-owned economy was not exclusive to the Deng era, but in fact took its roots in Mao Zedong Thought.

The leading role of SOEs in China’s economy has far-reaching effects. The CPC can regulate investment levels; allowing for much needed investments during economic slumps, and into projects rejected as unprofitable by private enterprises, such as infrastructure, public facilities, and the riskier spheres of scientific and technological innovation. The CPC also has greater influence over micro-economics, i.e., the activities of individuals and firms, than Western capitalist nations. The state-owned sector is empowered to influence the activities of enterprises operating under different ownership structures, typically collective, cooperative, or mixed. Additionally, in order to guide the activities of the private sector, the CPC maintains an active presence of party cells within private businesses. A survey conducted by the Central Organisation Department found that 68% of private businesses had party cells by 2016, and 70% of foreign enterprises. Those that fail to adhere to CPC guidelines risk being shut down completely and absorbed by the party. On the other hand, preferential treatment is shown to businesses that contribute to the goal of building common prosperity, such as tax reductions for those prepared to take on more innovative projects. The CPC also imposes penalties on individual billionaires who violate regulations relating to foreign investment and shareholding, borrowing of public funds, concealment of personal shareholding, and buying and selling stocks.

Unlike free-market capitalist economies, China’s economic development adheres to medium and long-term economic plans, which are determined based on socio-economic tends and projections of the performance of the economy as a whole. One such example is the Five-Year plans, the blueprint of China’s economic development, which currently champions urbanisation and rural revitalisation.

China’s banking system is another important sphere of state regulation, with the CPC taking measures to prevent any possible manipulation in favour of individuals or interest groups. As a result, the substantial growth in China’s national wealth over the past few decades serves to enrich society, rather than a few rich individuals.

Additionally, land in China is publicly owned. In urban areas, land is owned directly by the state, and is possible to lease for a certain period, but only following approval from the CPC and with additional government stipulations. In rural areas, land is owned by collectives and limited to agricultural use.

The difference between socialist market-economies and free-market economies becomes abundantly clear when contrasting China to India, both nations of comparable development and population. Since 1978, China has sustained an average growth rate double that of India, and has successfully lifted its people out of poverty, while the majority of Indians remain in absolute poverty.

Evidently, China has not “lost its socialist mainstay” as critics claim, as SOEs continue to play the leading role within the economy, directing development towards the realisation of socialism, and private capital remains subordinated to the CPC.

The Theoretical Basis of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics

Even among the left, some put forward the belief that ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ has abandoned the core principles of Marxism, pointing to the CPC’s acceptance of private enterprises and markets as evidence of this point.

In the words of Jiang Zemin: “[Socialism with Chinese Characteristics] is the product of the integration of the fundamental tenets of Marxism-Leninism with the reality of present-day China and the special features of our times, a continuation and development of Mao Zedong Thought, a crystallization of the collective wisdom of the entire Party membership and the whole Chinese people, and an intellectual treasure belonging to them all.”

As the period of transition between ‘dying capitalism’ and ‘nascent Communism’, the form Socialism takes will differ based on the peculiarities of every nation and its material conditions. Taking a dialectical approach, Marx and Engels rejected rigid and immutable definitions of Socialism, with Engels writing: “like all other social formations, [Socialism] should be conceived in a state of constant flux and change.” In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels elaborate that the development of socialism depends “everywhere and at all times, on the historical conditions for the time being existing.” In the Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx outlined communism as a process divided into two distinct stages. The lower stage would retain some of the “birthmarks” of capitalism, while the higher stage represented a fully developed communist society.

Clearly, Marx did not believe that higher stages of development could be achieved by bypassing or rushing through lower stages. Based on this understanding, Chinese economists have also envisioned socialism as a multi-stage process, with China situated in the primary, underdeveloped, stage of socialism. As a result, emphasis has been placed on the urgent tasks of developing the productive forces and improving the living standards of the most impoverished members of society.

Again in The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels argue: “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralise all instruments of production in the hands of the State, i.e., of the proletariat organised as the ruling class; and to increase the total productive forces as rapidly as possible.” As John Ross clarifies in his book China’s Great Road, the use of the term “by degree” indicates that Marx and Engels envisioned the transition to communism to be a prolonged period in which state-owned and private property would co-exist, just like China’s economy. Engels reaffirmed this in 1890, that the gradual building of a socialist society seemed to him “quite feasible”. Lenin echoed this point in 1918, critiquing dogmatic conceptions of Socialism, he stated that: “the transition from capitalism to communism takes an entire historical epoch.” Clearly, the idea that Socialism can be constructed in one-stroke deviates from the writings of Marx and Engels and not vice-versa.

According to Marx, distribution within a socialist society operates on the principle of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his work” and within a communist society on the principle of “for each according to his ability to each according to his needs”. In China, distribution predominantly corresponds to the quality and quantity of someone’s work, particularly for those employed within the state-owned sector. The constitution of China affirms that: “the State upholds the basic economic system in which the public ownership is dominant and diverse forms of ownership develop side by side and keeps to the distribution system in which distribution according to work is dominant and diverse modes of distribution coexist.”

Socialism with Chinese Characteristics represents a creative interpretation of Marxism applied to China’s unique material conditions, rather than an abandonment of its principles. This doesn’t mean to say that contradictions between the state-owned sector and private-owned sector have ceased to exist in China, nor that further challenges will not arise. It does however mean that the CPC, armed with the science of Marxism, can confront these challenges and overcome them.

Charlotte Jones and Rares Cocilnau are members of the Young Communist League’s London branch