On 10 March 2023, the world awoke to the second largest bank failure in American history. Whereas the financial crash of 2007-8 took place over the course of months, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) occurred in just over forty-eight hours. We are witnessing another global banking crisis: a crisis entirely predestined by the nature of banks and their reliance on fictitious capital.

To understand how banks crash, we must know how they grow to begin with. Put simply, banks loan money that is deposited with them, and charge interest, such that they end up with more money than they had before giving out the loan. Banks can also sell financial products, such as securities, which are in essence portions of loan debt owed to the bank. As the debtors pay back their loans and interest, the owners of the debt represented by these financial products receive a proportionate amount of the repayment and interest. Since banks will scrutinise loan applicants to ensure they will be repaid, buying a financial product derived from this debt would be considered a low-risk investment.

The financial products themselves don’t even need to be held until the debt is paid: they are assets with a market value, and can be around from investor to investor, for a profit. Often, this exchanging can deliver even greater and faster profits for capitalists exchanging them, compared to simply holding onto them.

So, banks allow capitalists to make extra profits from capital itself. But this leads to a disconnect between the capital gained from buying and selling financial products and the ‘real’ capital that was loaned, repaid, etc. The trading value of these financial products becomes orders of magnitude greater than the ‘real’ capital that they represent. Karl Marx described this phenomenon as fictious capital.

Capital that has not been materially realised, yet is valued speculatively, is defined as fictious. The modern banking system now relies on fictitious capital to turn profit. But as Marx observed nearly 200 years ago, there arises severe contradictions within these means of accumulation, for when the real capital is not realised fictious capital disintegrates and the results are catastrophic.

The 2007-8 financial crash is the perfect illustration of the fictious bubble bursting. In 1999,the Clinton administration repealed the Glass-Steagall Act, deregulating American banks and encouraging high-risk strategies. One such strategy was subprime lending: banks deliberately approved mortgages to applicants that they knew would not be repaid. From the perspective of the banks, the mortgages repayments themselves were not as great of a profit device compared to the sale of the securities derived from them to investors. This meant banks were incentivised to issue as many mortgages as possible, even to those with no ability to repay, to sell the maximum amount of securities.

The result was working families having a bizarrely easy time getting mortgages, and investors valued the securities on the assumption that banks ensured they would be repaid. But by 2007, this collective fiction shattered. A growing number of repayments had failed to be met. When this news was broken, it became clear the real capital promised to owners of securities would never materialise. Then the fictious capital was subsequently destroyed: the trading value of securities plummeted; the billions of dollars invested in them evaporated.

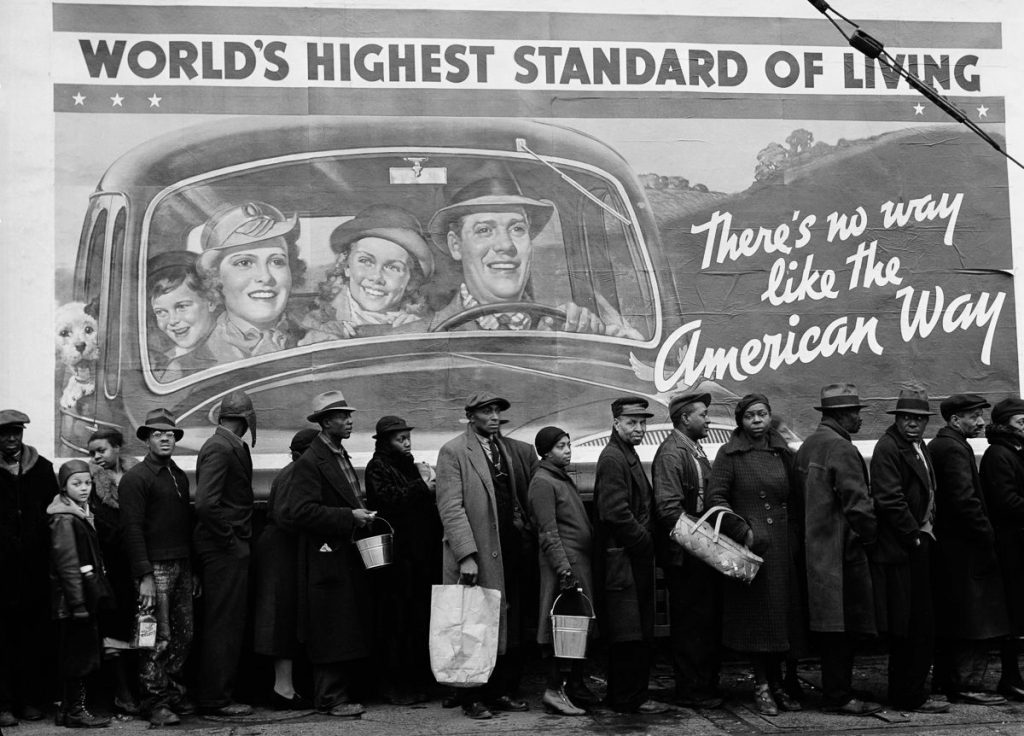

It is important to note that those who see the gain from these investments are the bankers themselves, in the form of dividends and bonuses. By contrast, the real ‘risk’ to the things important for a dignified life, are placed entirely upon the innocent customers. When it became clear they could no longer profit from sales of securities, the banks pressed their mortgagors to repay, repossessing homes and making thousands of families homeless. While regular people suffered with some of the highest rates of unemployment ever seen, the banks were given billion-dollar bailouts; over £137 billion was paid to prop up banks by the British government. The relationship between the bourgeoise and the capitalist state is never seen more clearly than in a financial crisis.

After the housing crisis in America new legislation was enacted to ensure banks met minimum liquidity requirements, ostensibly requiring banks to hold enough real money to honour securities. The hope was for banks to adopt more ‘sensible’ investing. Yet no matter how financial capitalists operate their business, they will need to rely on fictious capital. By its nature, this fictious capital grows to be greater than the capital held by the banks, and the inevitable disaster occurs. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has been blamed on inflation by the liberal media. I will explain why this is not the full story, and how SVB is an illustration that ‘safe’ investing is predestined to the same ends as the ‘risky’ investing blamed for the 2007-8 crash.

The role of inflation is certainly indicative of capitalism’s dysfunctional nature, and worthy of some digression here. Take the ostensible reason for the current extreme levels of inflation: the war in Ukraine. Simply put, inflation is the decline of the value of currency. We typically experience this as an increase in the cost of commodities. The resulting damage to supply chains due to the war, is an inflationary drive but it is not the cause of inflation. If the price of commodities increased in proportion with the costs of running a business, profits would surely keep pace with pre-inflation levels. Instead, we see record-breaking corporate profits over the last year.

So, as Russian and Ukrainian workers are sent to die on behalf of their ruling classes, corporations find an opportunity drive their prices up. When prices are hiked, unions fight for higher wages to match them. This means more money is in circulation in the economy, and so the value of currency decreases. Inflation is caused by the greed of some capitalists, which in turn devalues the wealth of other capitalists. The ruling class need to use the institutions of the state, in order to resolve these massive contradictions.

Central banks work on behalf of governments to stop inflation from happening. The only method the central banks use to combat inflation is raising interest rates. Interest rates are the proportion of a loan, typically expressed as a percentage, that is charged to the borrower. So, when interest rates increase, the costs of borrowing increase. This is designed to suck the excess money out of the economy, thereby increasing the value of the currency. But the managers of the economy overlooked the impact this adjustment would have for fictious capital.

Bonds are similar to securities: these are portions of debt that investors can purchase and trade around. However, instead of representing money borrowed to bank customers, bonds represent money borrowed by a government. When a bond is purchased, the buyer is effectively lending their money, and the government guarantees to pay it back. The return to the owner is known as the yield, and it is determined by the interest rate at the period of the bond being issued. As such, bonds are considered the low-risk investment—short of a calamity like civil war or natural disaster befalling the country issuing the bonds, there’s no situation in which a government can’t pay back.

When central banks increased interest rates in reaction to inflation, new bonds became more valuable, since these will yield a greater return for owners. However, this had a knock-on effect for older bonds: if these new bonds are on the market, why would investors ever want to buy the old bonds, with lower interest rates? The value of these older bonds, which many financial businesses had heavily invested in, went into freefall. The ‘safe’ fictious capital bubble imploded.

In Britain, we witnessed Liz Truss’ premiership end after just 50 days in office, when doubling interest rates caused the value of bonds (named ‘gilts’) to rapidly decay, and only narrowly avoiding pushing pension funds into insolvency. In America, we now see the fall of Silicon Valley Bank. With bond values nose diving due to the central banks hiking interest rates, SVB was forced to sell their bonds at an extreme loss to meet the minimum liquidity requirements set after the American housing market crisis.

Customers observed this with alarm, and rushed to cash-out, causing a ‘bank run’. Bank runs are caused by customers rapidly withdrawing money from their accounts, depriving a faltering bank of what real capital it has left. With the advent of the internet and mobile banking, bank runs have become incredibly dangerous because they now happen almost instantaneously. In the case of SVB, there was a 48 hour window for those in charge to find a solution.

In Britain, a deal was brokered for HSBC to buy out the UK division of SVB for £1. The Biden administration, reticent to fund healthcare for working people, has offered up hundreds of billions of dollars to assure the bank’s customers and investors that their wealth is protected. There is no victory to celebrate in the headline stories.

Had these short-term solutions not been found, there would have been economic cataclysm. Within the tech sector in the UK and America, businesses would have gone bust, people would have lost jobs, lives would have been ruined overnight. Because of the financial market’s dependence upon fictitious capital, it is not a matter of ‘will this happen again’ it is a matter of ‘when’. The critical mass of fictious capital has already grown, and what we see is the capitalist class barely restraining it. When the whole thing collapses a final time and they cannot catch it, you can be sure it will once again be working people left to live with the consequences.

One of the major banks in Europe, Credit Suisse, has also collapsed, following SVB. Credit Suisse is the most exposed large European bank to the American economy. They had a track record of gangsterism and corruption, confessions about material weaknesses, and, catalysed by the collapse of SVB, they experienced their own bank run.

Credit Suisse is a much larger bank than SVB and the turmoil that it came under was described by Nouriel Rubini, the prominent American economist nicknamed ‘Dr Doom’ after predicting the housing market crash, as a potential “Lehman moment”, referring to the crises of 2008. This is the kind of world that capitalism creates, enormous economic institutions operate in perennial instability through the creation of fictitious capital for the sole purpose of profit.

Interest rates are continuing to be raised to combat inflation across America, Europe, and England. As we have seen, the hiking of interest rates works only to heighten the contradictions of the system. Meanwhile not a single politician looks to any other resolution, not one single voice in parliament, not one single mainstream media figure. The ruling class do not present alternative methods of combating inflation because they would damage bourgeois profit; they do not care about the impact upon working people because they see it as the necessary collateral in their relentless desire for more money. The capitalists know that the system is rigged to protect them, the banks and big business loan billions to governments and governments return the favour with cheap money after the inevitable bust.

Price and wage controls would seem to be one means of combatting inflation. Perhaps some more laws can be passed to prevent banks from creating too much fictitious capital in the short term. But these kinds of methods, the methods of reform, are never complete solutions. Regulations come undone, and so long as we have an economic system that prioritises private profit over human wellbeing, there will always be a draw to fictious capital. The only solution lies in the abolishment of private capitalist enterprise, and its replacement with a socialist model of production. The nationalisation of all banks and economic institutions will end the cycles of boom and bust. The socialisation of corporations will prevent the commodity price hiking which causes inflation. But the longer we wait while they remain under private ownership, the closer society steps towards completely avoidable turmoil.

Ellis Rae, is a member of the YCL’s Liverpool Branch