After the destruction that came with the Second World War, the communist governments of Eastern European countries were met not only with the grand task of rebuilding their economies but also with the transition into socialist economies for the first time. Although there were inevitably a number of flaws with socialist planning and execution, especially in regards to nations that had turned communist only after the war, it is undeniable that the socialist economic system managed to rebuild these nations despite all the challenges ahead. Using the USSR, GDR, Poland, and Albania as case studies, this article will very briefly examine how the socialist system dealt with poverty and societal problems. In particular, it will take a closer look at the transformation of the countryside and the lives of ordinary citizens.

USSR

Aside from establishing control over new republics, the Soviet Union was spared from the pain of transitioning into a socialist country. Nonetheless, they still had to deal with the damage left by the Nazi occupation as well as the loss of over 27 million citizens. The Soviet parliament decreed in November 1945 to begin the immediate reconstruction of the 15 biggest Russian cities affected. Cities in other Soviet republics that were prioritised to be rebuilt were limited to their capitals; namely Kiev, Minsk, and Chisinau. Most large scale works were completed by the time of Stalin’s death, though individual buildings and streets were neglected until the 60’s.

In addition to rebuilding several towns and cities, the government had undertaken several new pre-war construction projects such as the Volga-Don canal, which was finished by 1952. Additionally, the Soviet central bank oversaw the reduction of prices between December 1947 and 1954. In total, the Soviets saw reductions in prices six times in that period.

The first set of products that were made cheaper (at around 10-12%), was bread, buckwheat, and flour. In the UK, bread rationing was actually brought in after the war and ended 8 months after their Soviet counterparts. While the reduction of prices for certain products wasn’t unheard of, as this was accomplished back in the 30’s during the second five-year plan, it’s impressive nonetheless for a government to not only end rationing of food only a handful of years after the war where food conditions were close to famine, but also to lower the prices for ordinary civilians for basic products.

The process of electrification was also continued, with the USSR taking the 2nd place- behind the US- globally for most electricity produced shortly after WWII. From 1950 to 1970, Soviet electrical energy increased from 91.2 billion kWh to 740.9 billion kWh. To give some perspective, UK electricity production today amounts to around 310 billion kWh. The fast tempo of electrification meant not only a functioning and improving economy, but also meant an improvement in living standards for those in more remote towns and villages.

An even more demanding matter at hand, however, were store shelves in cities that relied on food from the countryside. The amount of food available to the average citizen in 1946 and beginning of 1947 was particularly meagre, and it was becoming apparent that something must be done to avert another Holodomor. Although the government announced grand projects such as “great plan for the transformation of nature”, the Soviets were still in desperate need to first rebuild those villages and kolkhozes that previously functioned in Ukraine and the Kuban region of European Russia.

Surprisingly enough, attention to rural reconstruction was paid mostly from local town officials or even villagers themselves, as central and regional governments were more concerned with restarting heavy and light industries. This unexpected laissez-faire approach from Stalin (be it intentional or not) resulted in an inconsistent planning system and a lack of regular inspections led to safety breaches and messy construction styles in most villages.

Following Khrushchev’s consolidation of power, the issue of rebuilding the countryside was finally brought up in Moscow and led to the famous Virgin Lands campaign; essentially replacing Stalin’s “transformation of nature”. This time, stricter regulations and uniform planning managed to create a more coherent village system in the affected regions throughout the late 50’s and 60’s and made it possible to create a permanently stable food supply.

Poland

The three colossal tasks for the new government was to rebuild several cities including the capital from scratch, reduce illiteracy rates which stood at almost 20% in 1949, and to establish socialism in a country with a population that has been previously hostile to the Soviet Union given their turbulent history. The first task was completed gradually and in steps.

The area that was immediately rebuilt within 10 years was the historic Warsaw city centre. Construction teams were concurrently involved with the building of brand new neighbourhoods for residents, and starting from scratch meant that urban planners could now design modern apartments and facilities; a dream for pre-war architects. These new homes normally featured all amenities of a modern flat, as well as access to nearby services. This was in contrast to the many slums that had dominated Warsaw’s suburbs in the 1930’s.

The problem of illiteracy was tackled in 1949, when the government issued a new campaign to promote education for peasants, especially those in poorer regions. Indeed by 1952, the percentage of illiterate adults went down to only 1.8%. After the controversial 1950 monetary reform, for the average worker, real wages went up by approx. 3.55% per annum from 1950 till the transition to a capitalist economy. If this rate remained undisrupted by post-communist shock therapy, the average monthly wage would be almost twice as much as it currently is (3800zł compared to a hypothetical 6280zł).

One major pre-war issue that was resolved, albeit slowly, was the agricultural question and the redistribution of land. While it is true that 65.6% of available land was redistributed to peasants, state farms took a large portion of the pie, accounting for 18.2% of the distributed land. Still, leading Polish communists approached the topic of state farms and collectivisation carefully, as they knew that following the Soviet model would not be readily accepted in Poland nor would it work out as planned.

This skepticism was strengthened after 1956 as the Party initiated political reforms and slowed down collectivisation of large farms that were still beneficial for the economy. As a result of the land reform, by 1949, the average private farm size had only increased by 1.9 hectares, still below that of many western farms. However this can be compensated for by the fact that over a million young peasants moved into the cities in search of new careers and educational pursuits. This internal migration saved the Polish countryside from being overpopulated in the 1950’s, as well as strengthened the workforce in developing cities.

Sadly, history proves that the downside of domestic migration is the temporary halt to high standards of living. Indeed this was true for Poland also, where the standard of living for urbanites after the war did not increase as rapidly as it did in already industrialised countries like the USSR or East Germany. This was exacerbated by Poland’s six-year plan (1950-1955), which put pressure on expanding heavy industry in the context of the Korean War.

East Germany

This was also a fascinating example as far as political and economic changes are concerned. The German communists’ priority apart from rebuilding the country was to denazify institutions and organisations across the GDR. Compared to the “free” West, East German denazification was highly efficient in the sense that essentially every court, council, and government office was cleared of people who had previous affiliations with the Nazi Party.

In the West, not only did many former nazi judges and lawyers retain their posts, but also allowed for the existence of an openly fascist and pro-lebensraum ‘Socialist Reich Party’ until 1952. Even after its eventual ban, the members simply merged into another ‘Deutsche Reichs’ party, which was never banned by West German courts. The West provided comfortable lives for several nazi generals and officers from both the Wehrmacht and SS after the war, including those who were confirmed to have committed crimes against humanity. A famous case is that of Heinz Reinefarth; a war criminal who murdered civilians in the Warsaw uprising. A Hamburg court decided to set him free on the basis of “lack of evidence” and went on to become mayor of Westerland. A similar figure who escaped justice was Kurt Meyer, a convicted war criminal responsible for mass murder of Canadian prisoners.

East Germany also took a heavy toll financially and economically from the very beginning of its existence. The areas that covered East Germany were primarily agricultural, with the exception of a small industrial region around Leipzig and Dresden, which had been nearly completely destroyed by allied bombing campaigns. In contrast to West Germany, which was invested in by the US through the Marshall Plan rather than paying reparations, the East German government was responsible for providing war reparations to those countries affected.

Economic and educational reconstruction was also hampered by a massive brain drain as academics and medical professions among others left for wages that the East German institutions simply couldn’t provide unlike West Germany. This got particularly bad in 1961 in Berlin, resulting in the construction of the Berlin Wall. Despite this, the East German GDP rose by 73% by 1955 owing to the success of the 1st 5 year plan; an impressive increase by any measure.

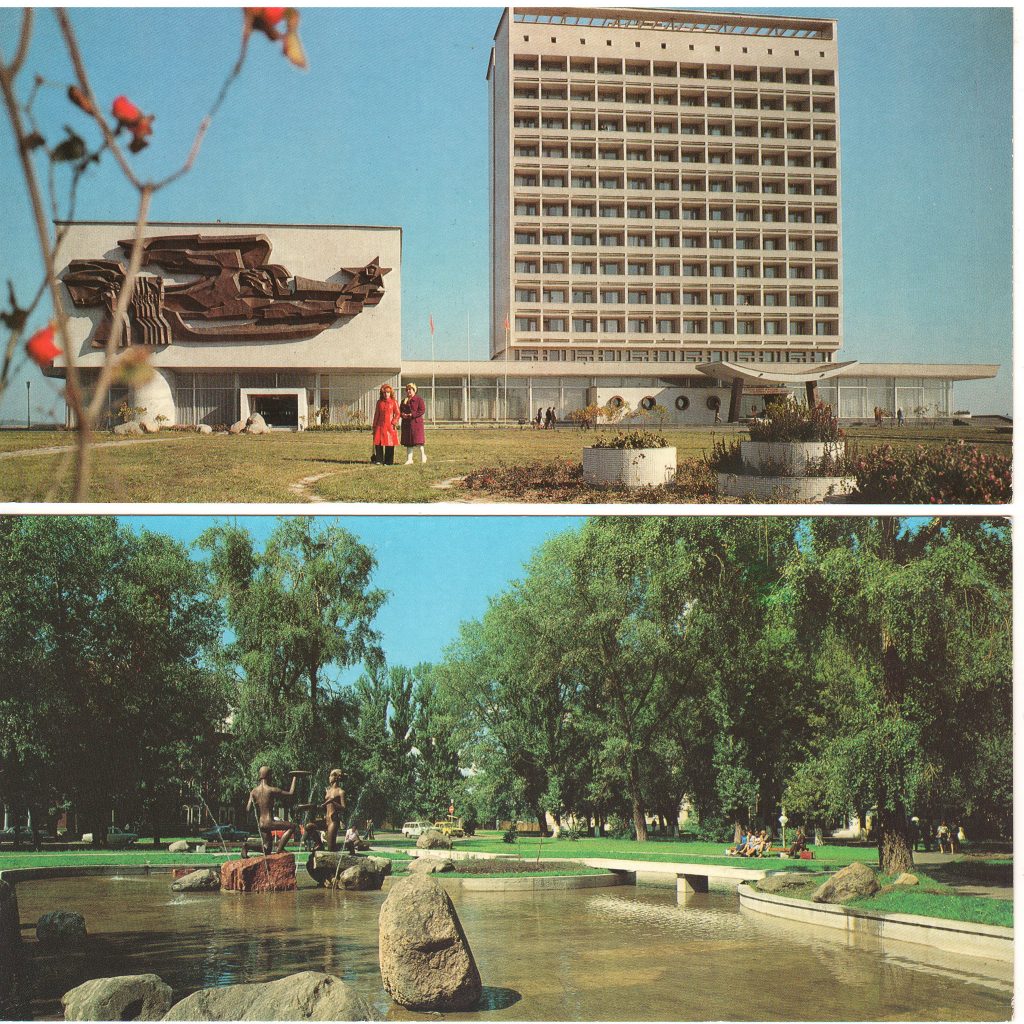

By 1960, the GDR was the fifth most industrial European country Focusing on consumer goods and exports in the 1960’s, the GDR became one of the most successful Eastern Bloc countries, with citizens enjoying a high standard of living, relatively well paying jobs, and apartments that were costing only a small fraction of an ordinary worker’s wage thanks to rent controls across major cities.

Albania

In the interwar and war periods, Albania was one of the poorest countries in Europe and in many cases one of the most backwards rural societies, with tribalism still being present in most rural areas of the country.

As in many other European countries in the first half of the 20th century, Albania’s arguably most pressing issue was the redistribution of land among peasant families. Redistribution of land based on need was debated and formally passed as a law in 1930 by the reactionary parliament under King Zog I. The reality of this reform was much more depressing, as this only led to a small fraction of land being distributed to Kosovar refugees.

When Albania became an independent socialist nation under the Party of Labour (PPSh), it found itself in a situation similar to what the Soviet Union found itself in in the wake of the Russian Civil War. Another land reform law was passed in 1946 to reorganise the now-wrecked economy. This time, with the help of Yugoslav geologists and technicians, 40% of arable land was redistributed from larger estates, and this slowly continued into the 1950s, when 90% of land was affected.

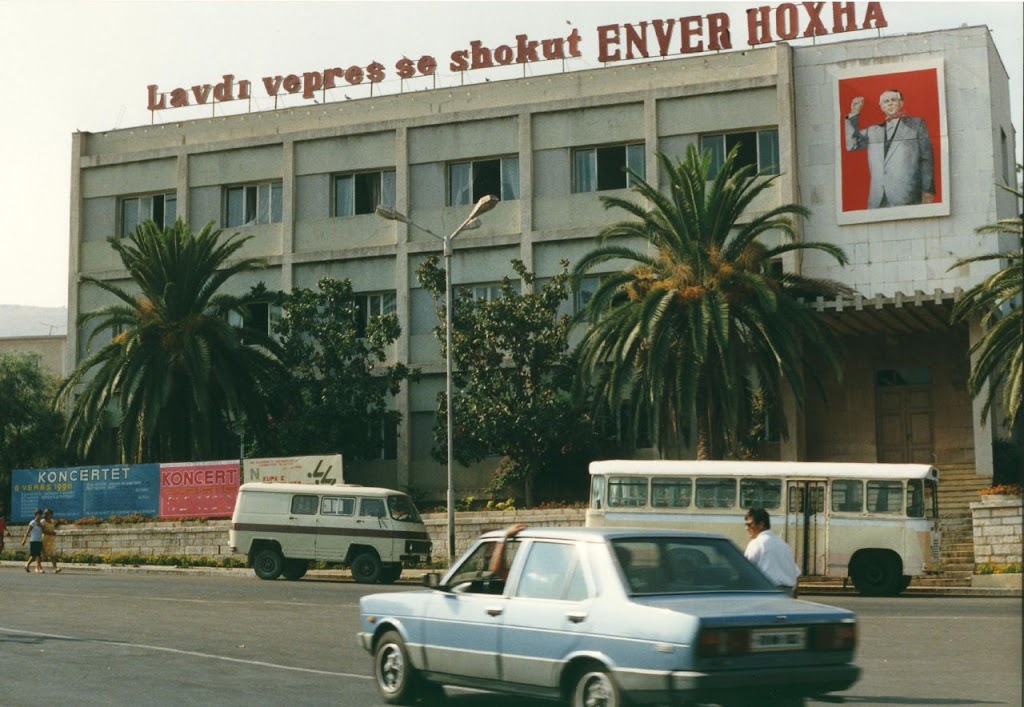

Land redistribution ended as a major success in the early years of Hoxha’s administration, as agricultural production surpassed pre-war levels in 1948; only 2 years after the law passed. The social groups that profited the most from this were the poor peasants and landless tenants, as well as those whose farms were 5 hectares or smaller. Overall, 70,000 families benefited from this decree.

Additionally, friendly relations with Yugoslavia until 1948 was helpful to the economy, as Albanian raw resources were exported at an attractive price.

Progress in other areas can also be noted, including the first commercially available railway line being built in 1947 to secure reliable transport links across cities with other lines opening up throughout the 50s and 60s. Just like the focus on building interstate highways in the US was reasonable after the Second World War given their fast growing GDP per capita and disposable income, the focus on public transport in Albania made sense, as the GDP per capita levels after the war made it practically impossible for the average citizen to purchase a private car and the demand for domestic immigration from villages to cities was high.

Thanks to university exchanges between Yugoslavia and later the Soviet Union, Albania possessed a relatively fair number of experienced mechanics and engineers, opening the way for industrialisation. The expansion of industry throughout the 50’s led to industrial production accounting for 41% of Albania’s GDP by 1960. With Chinese assistance later that decade, the numbers kept growing and increased to around 57% by 1980.

During this time, one group that began to fight for independence was women, who’s road to equality started as the employment of both genders was encouraged to fill spaces within new factories and farms. There were, of course, still disparities in pay between the two genders, but this wage gap slowly began decreasing in the 1960s and 70s as feminist groups began to protest this in their workplaces. The issue of women ‘s rights in more remote areas was never fully resolved, despite the official government policy promoting equality.

Another immediate problem faced by the AWP was illiteracy. Education in Albania was limited to higher social groups before WWII, and we know that the percentage of illiterate/half-literate citizens stood around 80% by the time communist partisans took power.

To combat this, evening classes were organised for peasant men and women. By 1950, around 345,000 more adults could read and write thanks to this programme, marking a 50% decrease in illiteracy. 5 years later, government channels announced that illiteracy amongst adults between 15-40 was wiped out.

While all this was going on inside the country, the newly reborn state had to avoid open conflicts with foreign powers including a spillover from neighbouring Greece that was in the middle of a civil war and still held historical grudges over southern Albania. Despite provocations from behind the border, Hoxha acted in a steadfast manner and following the traditional Marxist-Leninist approach decided to arm local peasants in border villages to catch any infiltrators or saboteurs, including exiled supporters of King Zog I. This then became the framework for Albania’s future approach to military doctrine- “people’s war”.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is entirely reasonable to state that the introduction of socialism helped the Eastern Bloc in the colossal task of economic and national reconstruction. Hundreds of communities, once poor and held back by reactionary elements, were at last brought into the 20th century. Education, industrialisation, and border security were the most common problems that were successfully tackled by the communists. At the same time, It is also true to state that a number of blunders and flaws were committed in the same time period. The sheer scale of reconstruction alongside the threat of potential western invasion led to decisions that in certain instances proved harmful to the populace.

And yet, should one judge those who were exploring all options in search for a better life, and use this as an argument against any new endeavors in the pursuit of socialist society? Or would it be wiser to use these errors as a lesson for the future? The answer seems obvious.

Mateusz Naglik