In 2010, the coalition government brought into force the Academies Act with the intention of transferring Local Authority schools to academy status, or ‘free schools’ that are managed in the same way. As of 2022, 39% of primary schools are now academies or free schools, accounting for 40% of the primary school population. 80% of secondary schools are academies or free schools, accounting for 79% of secondary school pupils.

The ostensible justification for this academisation process from various educational secretaries (of which we’ve seen five in the past four years) generally lends itself to the hallmark neoliberal rhetoric about lending greater ‘autonomy’ to schools purported by successive governments in their pursuit of market reforms in education. As is historically repeated, this market-led process falls short of the vapid targets for ‘inclusivity’ and ‘raising standards’ that academies set for themselves – notably due to the inherent contradiction between ‘inclusivity’ in a fundamentally exclusive neoliberal free market management model.

In a previously Local Authority school environment (not including the increasing competitiveness in the state school sector), deregulation and arbitrary policy making appear symptomatically because, as journalist Warwick Mansel notes, academies “are set up through contracts agreed in private with the DfE. The only semblance of ‘local’ scrutiny actually comes through a system of ‘regional schools commissioners”. A drastically top-down two-tier governing body is established, consisting of the trust’s members (corporate or individual) at the top and trustees (appointed by the trust members) who adopt the role of a governing body. In short, what appears is an adjacent managerial body that operates as a charitable business model. Decentralisation in this way has contributed to the creation of quasi-independent state schools that have, in turn, assisted in creating a ‘teacher retainment crisis’ and individual schools struggling to upkeep with increasingly competitive league tables. This is integral to any understanding of how and why academies – parallels to which can be drawn between Margaret Thatcher’s grant-maintained schools – are contradictory in practice in terms of improving prevailing as well as more recent issues in education.

Underfunding

The arrival at such a decision is, at least in part, the result of a top-down process headed by the significant underfunding of schools on a scale that lays bare a gross disparity between those in the most and least deprived areas. A 2019 NEU study revealed that cuts to cost per pupils in the most deprived areas amounted to a loss of 509 per pupil compared to 117 per pupil in the least deprived. Lack of adequate devolution has therefore played a role alongside uneven-handed allocation of resources in the hands of local authorities.

On the ground, the effects of academisation play out in a familiar fashion replicated by the process of privatisation of public services moreover: Decentralisation of management means poor communication, whilst hyper-focus on league tables replaces meaningful teaching practice that ‘enrichment schemes’ and their various synonyms promise to deliver. Additionally, external financial initiatives wedge a widening gap between inner-school management and academy governors – even more so when they take the form of Multi Academy Trusts (MATs) that manage multiple schools. The recent Schools Bill unrolled plans for every school to be part of, or “working towards” becoming part of a MAT by 2030 – “great teaching for every child” being the all-familiar mantra. As has been touched upon, the macro-management of MATs sees decision-making being driven by financial targets and investments that either undermine, or completely divert from, the real requirements of pupils in the classroom. It’s therefore difficult and even futile to try and marry “great teaching for every child” with a governing body so far removed both physically and functionally from teaching.

Greater autonomy granted to individual academies has also meant more arbitrary policy-making that can sometimes veer precariously from national documents such as School Teachers’ Pay and Conditions Document (STPCD) and the Burgundy Book, which outlines conditions of service for teaching staff and includes notice periods, retirement, sick pay and maternity leave, unless the teacher joined the school before the transfer to academy status. In light of this, we see an increasing infringement on the security of protections afforded to (especially new) teaching staff in addition to an overall lack of predictability. Couple this reality with payment conditions that have seen either annual real terms pay freezes or cuts since 2007, well before post-pandemic inflationary increases, it should come as no surprise that 44% of teachers intend to leave the profession by 2027– with a recent Nuffield trust study finding that 68% of teachers in the UK are now suffering from accountability-related stress and anxiety due to unmanageable workload that is exacerbated by hyper-focus on ‘raising standards’ in adherence to OFSTED metrics of improvement.

Outside the UK, accountability-related work stress was experienced by 45% of teachers on average. Meanwhile, an investigation by School’s Week revealed that thirty-two academy CEOs earned £200,000 or more – three more than they did 2019-20 – whilst being the furthest removed from the day-in day-out experiences of the schools they syphon funds from. Comparatively, the average starting salary for a new classroom teacher in an inner-city London school is 32,157, whilst new teachers outside London receive 25,174 per annum. The starting salary for a teaching assistant – for which 11,400 jobs were lost from 2011-2020 (a reduction of 16 per cent) – averages at 22,220 nationally. Educators can therefore be forgiven, surely, for a decline in morale with a starkly contrasting real terms pay freeze and forecasted pay cut.

A historical process

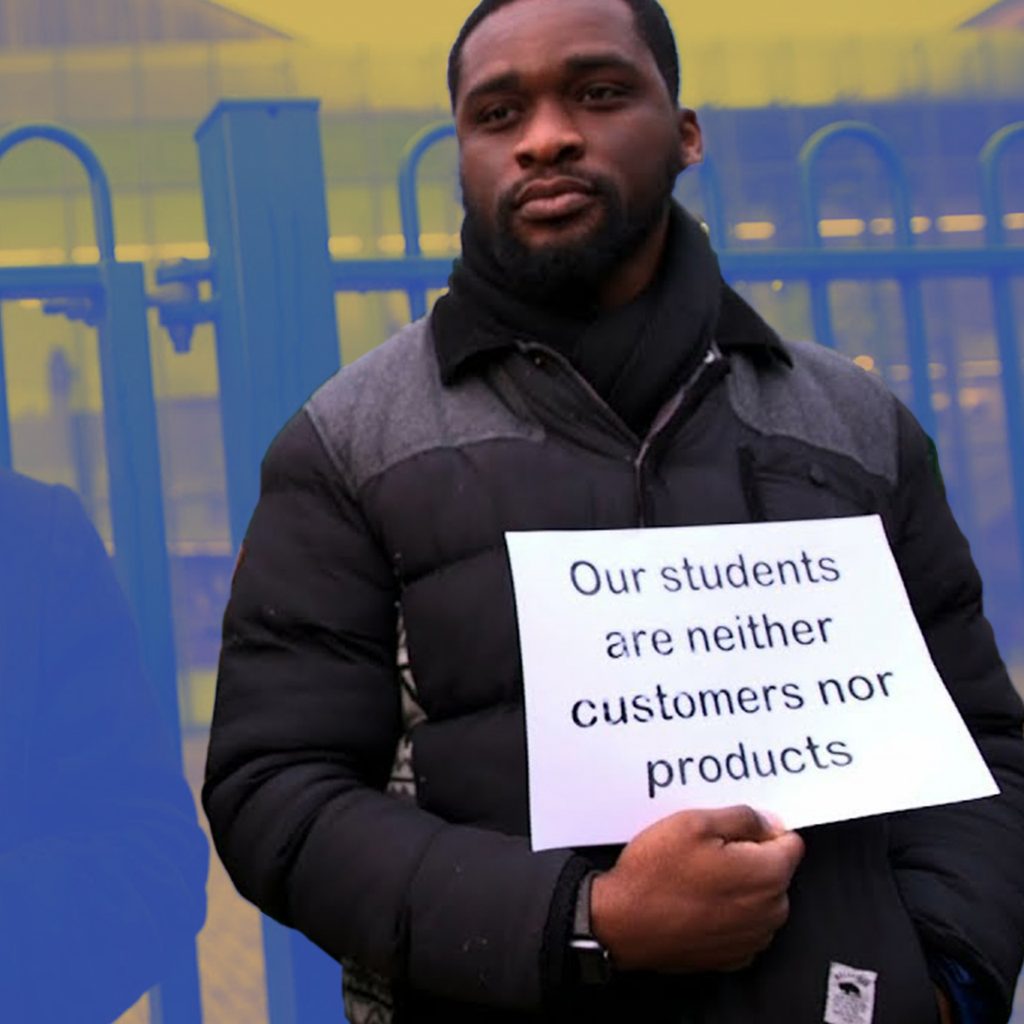

History points to this process as a continuum that can be located in recent living memory with Thatcher and John Major’s educational market reforms. In the state educational sector, the 1988 Education Reform Act introduced City Technology Colleges. These were secondary schools privately subsidised by investors from within the central government. The Act also initiated state schools with similar characteristics, which Thatcher referred to as ‘independent state schools.’ Through shifting power to private investment at central government level, an educational system founded on free market monopolies was effectively initiated. According to Thatcher herself when reflecting on the act in her memoirs, “Parents would vote with their children’s feet and schools actually gained resources when they gained pupils.” To paraphrase, parents were turned into consumers in an education market, and pupils became assets. In addition to various policies that further Thatcher’s neoliberal policies, such as the full privatisation of the Bank of England, in 2000 the Blair government introduced academies with ambitions of “driving up standards” of “failing Local Authority Schools.” Thus far, however, hyperboles about the effectiveness of academies in bolstering results and improving conditions for disadvantaged pupils have been disproven when measured. A 2018 survey conducted by the Sutton Trust and later applied in the NEU’s anti-academy campaign revealed that two thirds of academy chains perform below average for disadvantaged pupils. Once again, history stipulates that the purple prose and inspiring rhetoric about ‘equal opportunities’ within the context of marketising education doesn’t mask its fundamentally unequal outcomes when put to practice.

Moving forward

From Thatcher’s grant maintained schools to the more recent expansion of Multi Academy Trusts, the concept of ‘opportunities’ in education has become inevitably synonymous with market opportunities, and thus nothing but more of the same neoliberal lip service masking systemic inequalities with illusions of ‘growth and development’ that deliberately omit the real beneficiaries (hint: not the working class and certainly not working class children). The reality is that the next (and successive) generations need an education that values and fosters teaching and learning above competitive league tables; an education that sufficiently accommodates and funds pathways such as apprenticeships so that a range of skills and abilities are truly encompassed; and overridingly, the promise of stability post-16 regardless of whether or not young people choose to pursue further education. (This hasn’t included hostile policies outlined by Prevent, the dangers and extent thereof that would deserve an independent article).

As communists – or indeed anyone thinking objectively about the relationship between class and education recognises – the school-work trajectory is an inextricable one, and cannot be accurately analysed as a process divorced from the public sector moreover; cuts to which have flattened social mobility in the most callous and even morbid fashion. Based on average middle income, classroom teachers understand that on a socio-economic scale, we should theoretically and practically be in a ‘comfortable’ living situation, if we are to set our average salary as a middle-earners benchmark. With classroom teachers now resorting to food banks in certain localities due to a real terms pay cut of round 7% in the wake of a cost of living crisis, this loudly pronounces the gravity of the current crisis and the deepening threat that is forecast to workers in education and other industries whose annual income falls short of said mark. Lack of adequate funding to local authorities and the public sector more generally, in favour of private investment, is fundamental to the transfer from Local Authority to academy status.

Moving forward, this process must be resisted and coupled with organising and campaigning for recentralisation of resources to local authorities, as a key component in the bigger challenge we face in reversing and resisting privatisation.

Rhoda Stannett