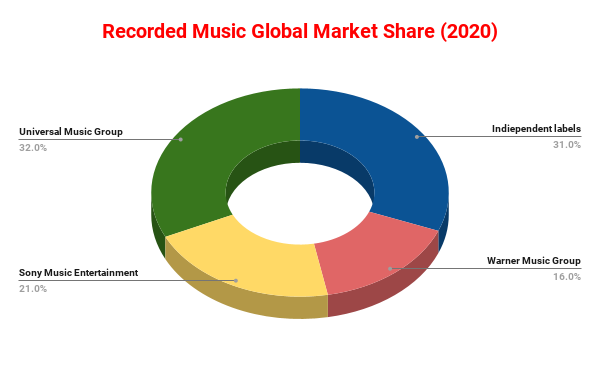

Like so many others, the music industry is highly consolidated. Even in the past twenty years we have gone from having a ‘big five’ major labels to a ‘big three’. It will not surprise you to learn that this ‘big three’ make up the vast majority of any metric you care to mention –– revenue, ownership, control of ‘stars’, etc. It is sometimes touted that independent artists and music companies are giving the so called majors a run for their money, with some statistics painting a picture intended to conceal the highly monopolistic nature of the music business –– but more on that later.

What this means for us all is that one of the important aspects of human culture has been corporatised and commodified. Do not expect me to make trite and trivial attacks on X, Y, or Z artist selling out or going mainstream. I wish it were that simple. Rather, I argue that the degree to which music has been not just commodified but securitised has meant that music and our understanding of it cannot be divorced from its commercial nature. That is to say, that the way we think about and deal with music in our lives is deeply tainted by the business that creates it for our consumption.

Before I go too far too fast let me quickly explain some basics. I will be mostly talking about music in terms of composition as opposed to a recording, this difference is important for what I will discuss later. In short –– a song can contain multiple different copyrights, these copyrights form the backbone of the whole music industry. In fact, if there were no legal system that protected the ownership of ideas, there would be no music industry. A recorded song (with lyrics) will have a copyright for the recording, a copyright for the music, and a copyright for the words of the lyrics. Record labels care about the first kind, and music publishers care about the other two.

Generally speaking, record labels make money by selling recorded music on CD, vinyl, etc., or now via streaming. Music publishers own the music itself, which means that they earn royalties from all performances or ‘sales’ of that music. When you hear about legal battles around song plagiarism, it is the publishing companies that get involved, not labels. Already it might be obvious the clear similarity in business model between music publishing and other intellectual property-based industries.

Much like how in the physical world there is basically nowhere you can go that isn’t ‘owned’ by someone, there is hardly anything you can listen to that isn’t owned either. Now before someone very clever jumps in and says: “what about Mozart? His music is public domain!” Remember, I mentioned that there are multiple kinds of copyright for music? Well, even if the music itself is public domain, there’s a very very high likelihood that unless you are listening in person that the recording you are listening to is very much not public domain. As with the music industry as a whole, the classical world is also represented by a small handful of companies (owned by the big three, of course!) who exist solely to endlessly re-record and re-release commercial recordings of ‘public domain’ music. And on the topic of public domain, I hope you like what’s already there as the music industry is dead set on endlessly extending the ‘life’ of copyright via lobbying.

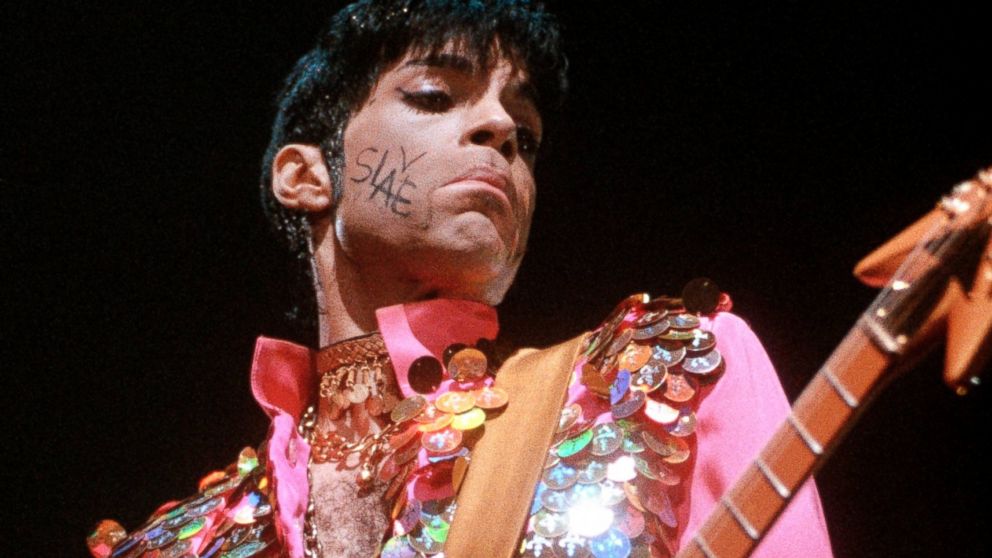

It currently takes usually around a whole century for copyrights to expire, usually the life of the author and an additional few decades after death. The companies pushing for this to be extended are not doing this because they want to support the families of their deceased writers –– no it’s because they can continuously make money off of popular music forever. In fact, the companies have a much easier time after the deaths of their biggest money makers –– cast your mind back to the great celeb cull of 2016. After their deaths, artists known for being highly protective of their work and legacies were suddenly putting out record amounts of music despite being dead. With the picky songwriter out of the way, music companies can begin to push the late artists’ estates to allow them to release music that the artist may never have wanted to see the light of day. While people die, companies live on and continue to cash in.

The music industry loves to paint itself as dynamic, creative, and full of innovation or people pushing the boundaries –– many people would probably agree with that from the outside. But if the real estate industry described itself like that, would people still agree? The music industry and real estate has a lot in common, especially the music publishing industry. Royalties for example might as well be rent, they both operate on the same principle of money paid for use of something owned by someone else.

At first you may find that confusing: “music isn’t like my flat, I’ve never paid rent to someone to listen to their music.” Except you have –– each time you listen to a song on Spotify or YouTube, a tiny slice of your subscription payment or some of the money the advertiser paid so you saw their ad is paid to the owner of the music. In that instant you make a minuscule payment in order to get a license to listen to the song, a license for a very personal performance of that song. When you buy a CD or a download you own the physical thing but of course you don’t own the songs on it in any meaningful way. This is because part of the price of the CD is given directly to the owner of the music on said CD as their royalty, or rent.

Now scale this concept up to the level of our friends the ‘big three’ and you can see how parallels to real estate become very clear. A key difference though is that this rent is not so much paid by individuals so much as it is paid by us collectively at the level of whole cultures. I say whole cultures because the ‘big three’ are alive-and-well all across the globe, and no form of expression in sound will not have some small or large part of it owned by them.

Of course, in the decadent and depraved West we are well aware that deeply ‘meaningful’ cultural touchstones such as Cardi B’s WAP, are sadly languishing as products cynically targeted and developed based on calculations about the fads and fascinations of the day, but it is not just a Western phenomenon. There will be very few countries on this planet which don’t have representatives of the ‘big three’ in operation.

Even in socialist countries like China or Vietnam, they are alive and well. In fact, within the industry ‘emerging’ markets such as these are seen as the next golden goose with much money being thrown in their direction. China for example has kowtowed to the interests of these international music companies, harmonising much of their copyright legislation with the rest of the world. This alongside crackdowns on illegal downloads meant China went from being seen as a waste of time for the industry to a highly valuable nut to crack in a matter of years.

But enough on how big-business is done by big-business. Let’s come back to my claim that the footprint of the major music companies goes far beyond their simple market share. While the ownership of the industry is something that can be calculated, their impact is something that is felt or perceived.

To some, the impact of the major companies is harmful only in so far that their size and business practices give them an ‘unfair’ advantage. To others the over commercialised flavour of their music leaves a bad taste in the collective mouth of music fans. There is some truth in the first point but the latter does not stand up to scrutiny. The prominence of the major labels and the way they operate has for decades determined not just how how modern music operates but also the what too.

Much of what I have spoken about so far is not true only for the ‘big three’, it applies down to the smallest companies too. The music industry is to its very core ambitious and predatory. The hidden id of even the most independent of companies is to grow ever larger and have an ever bigger roster of property –– songs and their writers too. To return to our real estate analogy, small music companies are the arrogant “I got my first mortgage at 24, now I own twenty flats” slumlord to the major music companies’ multi-billion pound property developer. The world of live performance makes it even clearer the degree to which as soon as any kind of ‘professionalism’ or career is introduced you run a fine line between subtle or outright grift, no one should be surprised that it was the music industry which birthed something as inherently demeaning as the ‘gig economy’.

So far we have mainly looked at how companies, big and small, do their upmost to own the immaterial and take the majority of their income from ideas protected by law. But what of another way in which the industry sinks it’s tendrils into us? In short –– the music industry divides people into their real existent self and a marketable idealised self. When I use the word marketable I mean it literarily, as in to bring to market.

The music industry (and not just pop, even leftfield genres) creates mythical figures who are the creators of the art, and everything that is tied up with it. Great lengths are gone to to ensure that this appears ‘authentic’, to ensure that these people who in a sense do not exist remain ‘relatable’ to us. You might say this is some sort of form of commodity-fetishism, where the person is first turned into a commodity to then exist in a new form within the minds of the consumer. It is no coincidence that the most successful of these people are ‘stars’, or more explicitly in Asia ‘idols’.

Members of the first social media generations will find this strange separation of real and idealised person far easier to understand and appreciate than people who grew up before it came about. This is because for the first time, one of the main elements of the commercial music world (and celebrity culture generally) is no longer solely restricted to the people involved but to some extent affects all of us who have some connection to social media. This logic is forced on anyone that actively engages themselves on any of the outwardly public facing social media platforms.

I would like to round this out by leaving the big stuff behind and talk about how this affects people on a human level. I would be lying if I said I understand Marx’s writings on alienation to talk about it authoritatively, but from what I understand I feel it is a useful concept to invoke here. The idea of ‘fake it ‘til you make it’ sums up perfectly how people approach beginning their ‘music career’, which let’s not forget is ultimately the desire to express their art but limited by the total control of the idea of what the music industry and the world is.

As someone who recently spent three years studying in a contemporary music university, I have seen first-hand what and how people are affected by this, and I am not simply talking about ‘burn out’. People who have barely developed their own idea of who they are and the music they feel they should make are spending more time doing what they are told they should be doing –– planning their marketing strategy, doing audience research, analysing trends, rather than actually doing what they want to do. These pressures are only exacerbated by the reality that you are just one among millions aspiring for the same thing.

In a twisted way, the ‘democratisation’ of music-making we have been told so much about in recent years (due to the internet and being able to record music on your phone) has actually resulted in the opposite. There is so much noise to push through (over 90% of artists registered on Spotify have fewer than 100 monthly listens) that regardless of what the music is those things that I complained new musicians have to focus on are crucial to any amount of success, even if your aim is as simple as sharing music with people.

It is a huge weight for anyone to bear, made worse by the uniquely personal nature of creating your own music and so I find it somewhat depressing that I cannot for the life of me think of any ways that this situation can be improved. Perhaps reducing how ‘democratised’ the world of modern music is might perversely improve the situation, for sure removing some of the unrealistic voices of institutions such as the one I studied at would help. These self-styled ‘universities’ exist to sell a dream, they are never explicit about it of course but they truly exploited a common dream of young people of stardom and creative success. There truly are no friends to the young idealistic musician.

If you have somehow managed to get this far through this rambling slog of an article I ask you to spend just a few minutes thinking about these problems and how we might address them…

How can we reconcile intellectual property exploitation and the need for writers to enjoy the fruits of their labour? How can a society and culture that understands music only through this lens be able to adapt to a system that exists without private ownership? Is the entire concept of music as we understand it itself a symptom of the underlying decadence of our society?

Harry Stephenson, is a music industry professional and YCL member