“Let the celebration of May Day win thousands of new fighters to our cause and swell our forces in the great struggle for the freedom of all the people, for the liberation of all who toil from the yoke of capital!”

Lenin ‘May Day’, 1904

May Day (also known as International Workers’ Day) is an annual celebration for the international communist and labour movements that brings workers from all over the world together. The celebration, which began 133 years ago, symbolises workers’ pride in defiance of the capitalist ruling class. Although it nowadays conjures up images of regimented Soviet parades, May Day’s origins can be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century.

Workers faced brutal factory conditions during the 1800s as a result of industrialisation. The length of the working day was one of the most draining aspects, with many people expected to work more than 70 hours per week, depriving them of leisure time. Workers in Australia, desperate for better working conditions, took a stand against their employers by organising an annual day of protest against the length of the working day. As described by Rosa Luxemburg:

“The happy idea of using a proletarian holiday celebration as a means to attain the eight-hour day was first born in Australia. The workers there decided in 1856 to organise a day of complete stoppage together with meetings and entertainment as a demonstration in favour of the eight-hour day… At first, the Australian workers intended this only for the year 1856. But this first celebration had such a strong effect on the proletarian masses of Australia, enlivening them and leading to new agitation, that it was decided to repeat the celebration every year.”

Rosa Luxemburg, ‘What Are the Origins of May Day?’, 1894

Three decades after Australia’s “proletarian holiday”, American workers decided to mark May 1, 1886 as the start of a national strike in support of the eight-hour working day. On May 4, workers protesting in support of the strikes in Chicago’s Haymarket Square were met with police repression, resulting in riots, gunfire, and even a bombing. Seven police officers were killed, leading to four of the protesters being hanged. The strike and the proceeding riot hit the international press and workers in other countries.

The Geneva Congress of the First International was held in September of that year, and it was agreed to launch an international campaign for the 8-hour day. The event inspired Marxists seeking to mobilise workers in the overthrow of capitalism, symbolising workers defying the state.

The Second International met in Paris in 1989 and decided that the following year, on the anniversary of the start of the Haymarket protests, an international day of protests would be held. As a result, on May 1, 1890, protests took place in North America, South America, and Europe. After proving to be a success, it was decided at the Second International’s 1891 Brussels Congress that May 1 would be designated as annual holiday. Since then, this day has seen millions of workers mobilise in their countries, protesting capitalism and inviting others to join the cause.

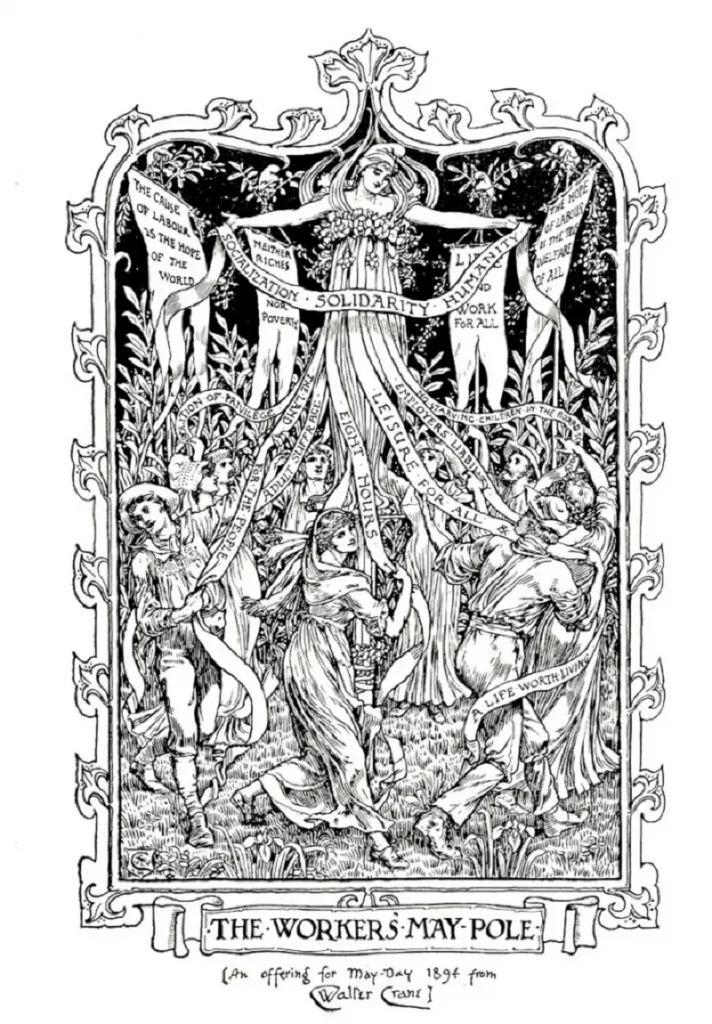

On the same day as the pagan May Day, Marxists from the Arts and Crafts movement attempted to combine the two types of celebrations into one. In his 1892 poem ‘Chants for Socialists,’ William Morris, known for his love of folk traditions, bridges the gap between the two celebrations, alternating the header of each stanza with “the workers” and “the earth”, fusing working-class pride with the pastoral celebration of the natural world. Both days are celebrated by ‘common man’ – but, whereas the pagan day marks the start of summer, the other champions workers’ power. Later in history, communist nations have made flowers a common motif in May Day propaganda to represent the changing of the seasons.

May Day has proven to be an effective piece of propaganda for the international communist movement since its inception. The most important day on the communist calendar, it allows us to demonstrate to our enemies and potential recruits the strength of our movement. For Eric Hobsbawm:

“It was a day on which those who were usually invisible went on public display and, at least for one day, captured the official space of rulers and society.”

Eric Hobsbawm ‘Birth of a Holiday: The First of May’, 1990

Following the October Revolution, May Day became an official public holiday in Soviet Russia. The ‘Day of International Solidarity of Workers’ was established in 1918. Whereas the Haymarket affair was represented by workers fighting against the police (the state), May Day in Soviet Russia couldn’t have been more different, with workers and the state marching together. May Day in the USSR was adorned with images of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and subsequent Soviet leaders, and it symbolised the pinnacle of Soviet identity. May Day represented everyone in society, regardless of age, ethnicity, or job, as evidenced by the diverse parade attendance.

May Day’s state-led parades gained international significance as socialism spread into Eastern Europe, China, Cuba, Vietnam, North Korea, and other countries. The largest May Day parades were held in the heart of capital cities (such as Moscow’s Red Square and Beijing’s Tiananmen Square), while regional cities and towns held their own. Attendance at May Day was mandatory in some former and current socialist countries, and those who did not attend were punished. The day became so integral to communist identity that workplaces and streets were named after it; for instance, 1 Maja Coal Mine in Wodzisław Śląski, Poland.

Without the benefit of state-funded celebrations, May Day was used as a platform to highlight contemporary issues for communists in Western Europe and North America. Whereas the USSR often used its May Day parades in the Red Square to show off military technology to the world, communists in the imperial core were protesting against the West’s Cold War aggression and the Vietnam War. In Britain, May Day has been used to highlight ongoing issues affecting workers domestically, most notably during the 1984-85 miners’ strike.

May Day has lost some of its communist image since the fall of the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc. Of course, China, Cuba, North Korea, Vietnam, and Laos continue to officially celebrate May Day – but we need to ensure that the communist roots of May Day elsewhere are not whitewashed by our opponents. Every year, as our movement grows, we must strive to increase the communist May Day presence.

The YCL is carrying on a centuries-old tradition this year by holding demonstrations across Britain. Our members are lining the streets with red flags under the slogan “MAKE THE RICH PAY!” in response to the cost-of-living crisis.

Solidarity to everyone celebrating May Day this year around the world.

Workers of the world unite!

Tomasz Nowak