In January 2022, the Saudi government started an initiative to destroy large sections of its second-largest city, focusing on historical working-class areas populated largely by poor Saudis, poor immigrants and poor former slaves. These demolitions have caused hundreds of thousands of people to lose their homes and is estimated to have caused up to one million people in a city of four million to be removed from their homes. In addition to the loss of livelihood and shelter, it has also destroyed areas that were previously safe-havens for immigrants that had lived in Saudi Arabia for generations. These demolitions are a continuation of historic trends in Saudi politics. An analysis of the situation can illuminate a large number of things about the internal politics of Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s internal politics are not often discussed by Marxists beyond what is usually discussed in mainstream media i.e. repression of women, protestors and immigrants. There is little discussion of the Saudi working class, or what the historical continuation of a lot of these problems are. I believe the reason for this is two-fold – the international implications of the Saudi regime are more widely known and are often more horrific and pressing (with Yemen for instance) and there is a dearth of modern Marxist analysis of Saudi Arabia as the underground Communist Party of Saudi Arabia was disbanded in 1991 and the internal politics of Saudi is hard to get information on from outside the country. I hope this article rectifies that lack of information slightly by providing some important historical context around what is turning out to be some of the most serious and important events in recent Saudi history.

There are two aspects of Saudi politics that are important to understand before we look at the demolitions, namely immigration and nationalisation. The current situation is very closely tied to these two trends, and it bears examining them closer.

Immigration and slavery

Immigration in Saudi has historically been a very important subject, yet has recently been overshadowed by discussions on immigrants being used as slave labour in the United Arab Emirates (specifically Dubai) and in Qatar (in light of the 2022 FIFA world cup). Those are, of course, very important to highlight, but as a result, the unique situation of immigrants in Saudi Arabia hasn’t been subject to much analysis, especially from a Marxist perspective.

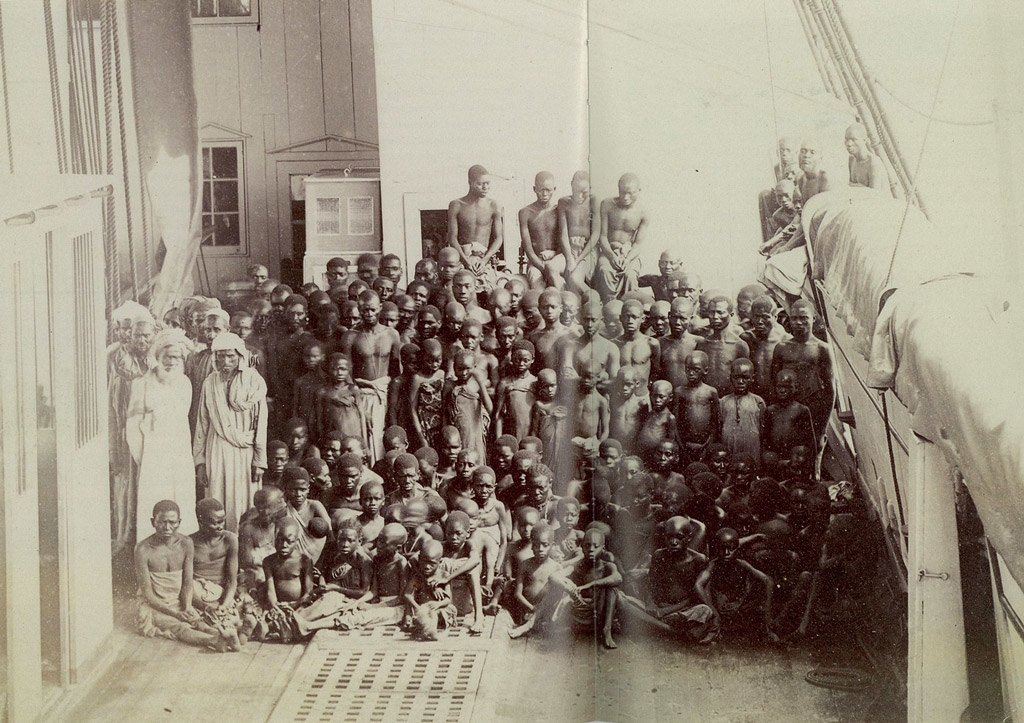

To understand immigration in Saudi, one must first understand chattel slavery there. Chattel slavery in Saudi Arabia existed officially until 1962, when the US pressured the then monarch to make it illegal in order to continue trading with the US. This is very recent history. My grandfather was a subsistence farmer and often sold extra crops in the market; he told me how often there would be a slave auction next to his stall with, in his words, “poor naked black people being examined by buyers.” There is a tendency amongst slavery apologists in the Islamic world to say that slavery was not racial. True, the justification for the slavery was not as tightly interwoven with race science as it was in the West, but it was very much racially disproportionate. Most slaves in Saudi Arabia were from East and North Africa. The descendants of those slaves now also live in the same tenements that are being depopulated and torn down by the Saudi regime. Chattel slavery, including sex slavery, was a widespread phenomenon. Upon it being made illegal, it was replaced by immigration.

The essence and form of slavery had now been dialectically changed to the slavery of immigrants. There is widespread knowledge of the situation of immigrants in the Gulf, but what is unique to Saudi is that immigrants took the roles of the former slaves. Once immigrants enter the country, they are locked into working for one company (or one person in a lot of cases), their passports are stripped away, they cannot own property or houses, their wages can be docked for any infraction, they can end up working for months unpaid, they might have no time off and might work 18 hour days, they can be threatened and be physically and sexually assaulted – and all this often with no legal recourse. This is true from the lowest class of workers (such as the ‘Harris’, a catch-all job involved with being on call 24/7 for taking care of everything in entire apartment blocks for as little as 5 GBP a day) to the higher class of workers (such as doctors). The biggest indicator that this system of immigration (called Kafalah) is a continuation of the system of chattel slavery is the official term that is used by the Saudi government to designate immigrants who leave their company or the person who sponsors them – ‘Huroob’ i.e. Escapee.

It is also important to understand the term ‘immigrant’ is misleading in the Saudi context. Almost every person who has no direct descent from people who lived in Saudi Arabia at the time of its founding are considered immigrants. There are people considered immigrants who are four generations removed from their ‘home country’. My family itself has lived in Saudi for five generations, and I myself, am third generation. We are all culturally Saudi and don’t know any other place as home except Saudi Arabia and, yet, because of racist policies, we are not considered Saudi and do not have citizenship. This is the case for many people who are today considered immigrants.

Immigrants are now being replaced en masse with a new generation of Saudi proletariat. With the introduction of policies such as the dependents tax in 2016 that caused the exodus of over a million immigrants, or Saudisation policies where each workplace in many industries must have a certain percentage of Saudi workers. This reframing of a Saudi working class and the Saudisation policy as a bid to phase out immigrants in more ‘skilled’ work are a vital component of understanding the current demolitions.

Nationalisation and Privatisation

Saudi Arabia is a strange mix of feudalism and early 18th century capitalism. There is still a system of feudalism as is apparent in the fact that a nobleman “owns” the red sea and any large-scale commercial activity that involves things such as siphoning sea-water for use in construction needs written permission from that nobleman. The 18th century capitalism is there in the sense that all commercial activities are at the King’s pleasure. This crystallises in several forms, from spurious taxes in order to bolster the royal family’s income to the complete seizure of the holdings of businessmen. While we communists applaud nationalisation, it is important to distinguish between capitalist nationalisation and socialist nationalisation (a distinction made in the British Road to Socialism as well). Saudi nationalisation is slightly different from western capitalist nationalisation as it involves the government seizing a company or large parts of an industry for the purposes of centralisation of power and increasing the wealth of the Royal family personally. This is a perverse feudal inversion of capitalist enclosure. A lot of these industries tend to continue to be run by private contractors, but the profits go to the government, such as was the case of the running of Universities for women across the Kingdom with their large scale introduction in 2014. This type of nationalisation is another key component in understanding the current demolitions.

We now have a base for our analysis of the demolitions, so we can start examining the developments.

The Demolitions

Jeddah is the second-largest city in Saudi Arabia, covering an area larger than London geographically and with a population of 4.6 million people. It is considered the “gateway to Makkah”, the holiest city in Islam and is the most multicultural city in Saudi Arabia with people from all nationalities living there and passing through there when they come to visit Makkah. It has huge populations of immigrants, former slaves and Arabs of all nationalities. It is also where the majority of the demolitions are taking place. It all started in 2020 in a place in South Jeddah called Souq Ahdal.

In all (admittedly limited) media coverage of the current demolitions, I have not seen any mention of the seizure of Souq Ahdal despite it being the model used by the Saudi regime for the current demolitions. Souq Ahdal was a very prominent market in the impoverished community of Ghulail in South Jeddah. A lot of the stores were owned officially by Saudis but secretly owned by immigrants through their Saudi partners (as immigrants cannot own property). It was a massive market that was the lifeblood of South Jeddah where tens of thousands of people lived, worked and made their livelihoods from. In late 2020, without warning, the government closed all the stores in the market and ordered the area completely depopulated. The government announced that all the land there had been sold illegally and was actually owned by a former King and was now the property of the current King who wanted it depopulated. The houses and stores were demolished or abandoned, and police cars were positioned around the ruins 24/7. Unbeknownst to any, this was being used as a controlled experiment to test the applicability of future demolitions and depopulations in Jeddah.

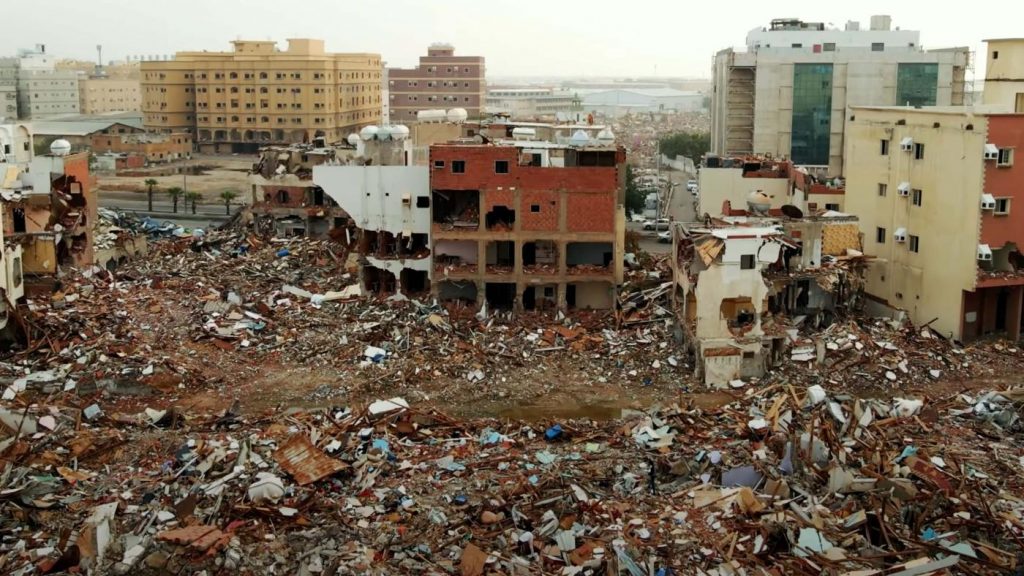

In January 2022, whole-scale demolitions of working-class areas in South Jeddah had begun. Entire neighborhoods in South Jeddah were demolished to a building. I drove through those neighborhoods in early March and it looked a warzone. Pariah dogs and poor people scavenging for metal populated what were once historical and thriving centers of working-class activities. Officially, the count of people depopulated from these areas was 500,000. AhlulBayt News Agency estimates the actual numbers are over a million people being removed from their homes in a city of almost four million people. In the beginning people were often given less than 24 hours’ notice to vacate their homes before the bulldozers flattened them, with authorities shutting off water and electricity to force them out.

The official designation by the Saudi government of these places as “slums” as a justification for their destruction is not completely accurate either. A lot of the places demolished were tenements by the standard of their upkeep and because of no government maintenance of roads, but the houses were generally traditional and functional homes built by people in the manner of unplanned development. The style of housing is close to being unique to the Saudi working class. They are only “slums” to middle and upper-class Saudis who do not understand the style of the housing being built as being a long-standing tradition of the Saudi working class and beloved by the people who live there. The landlordism that is prevalent in these areas is often what marks their predation and unpleasantness, not the houses themselves. Many of my family live in such places and have suffered greatly from such exploitative living conditions and landlordism and there is an argument to be made for creating better homes for people to live in, or to restructure the system of landlordism in these areas.

However, these are not the reason the Saudi government has started these demolitions. Most emblematic of this fact is that there have been little to no efforts by the Saudi government to rehouse most of the Saudi people who have been removed from their houses, no effort to restructure landlordism as a whole in Saudi Arabia and no effort at all to rehouse immigrants. Many families removed from their housing are sleeping in their cars or under bridges, there has been no attempt to provide even temporary housing for them. This was not done as an attempt to improve the living conditions of workers. Compensation for the land and buildings seized and destroyed are not universal and even then only paid to the extortionate landlords and not to people who have lived in the same building for generations paying enough rent to buy the house many times over. Let us examine the actual reasons for these demolitions, and not what the Saudi government say they are.

Firstly, of course, is the ever-present trend of centralisation of power by the Saudi regime. There is no power in Saudi except the power of the King, and any and all pretenders best beware. Whenever there is a fear of a businessman getting too powerful, his empire is immediately dismantled and swallowed into the Saudi regime’s holdings. A similar thing occurs when social capital is denied to the monster of centralisation that is the Saudi government. One of the main reasons I believe that South Jeddah was targeted as the starting point for these demolitions is that it was impossible to police it. Large swathes of South Jeddah were tenements and unplanned development, with tight alleyways filled with potholes that were, in places, untraversable by car. Consequently, police patrols in these areas were impossible and any police raids into these areas were suicide. When the police showed up en masse they were often pelted by rocks from the rooftops by a populace who had enough of their brutality outside these areas and were not about to have it in their neighborhoods. This left large areas of Jeddah that were unofficially outside the jurisdiction of the police force. These demolitions remove a huge thorn in the side of the regime, no longer will they have areas where their tentacles cannot reach in fear of being impaled. They also now own all the land in the areas that have been demolished which further centralises ownership in their favor.

Secondly, it is an attempt to restimulate the real estate market in Jeddah. Following the exodus of immigrants in response to the dependents tax mentioned above, the real estate market in Jeddah reached an all-time low. An apartment near where I lived that cost 5000 GBP a year in rent started costing only 3500 GBP a year and there were no signs of recuperation. After these demolitions, the rent in that same apartment now costs 7100 GBP a year due to mass exodus from South Jeddah to North Jeddah, with signs it will get more expensive as these demolitions continue. That is an unprecedented increase in rent, and stimulates a part of the economy that previously had been sorely affected by bad policy.

Thirdly, it is an attempt at the continuation of the previous purges of immigrants that will not affect the real estate market negatively. The dependent’s tax mentioned before was a tax on all immigrants of 80 GBP per month per spouse and child they had in the country. This is in addition to previous payments for residence permits and such which were equally exploitative. It is widely believed this was a thinly-veiled attempt by the government to cull the growing immigrant population it had because of the rise of racist and xenophobic sentiments both within and outside the government, that was spurred on by the propaganda arm of the state for decades. Many ‘unskilled’ immigrants lapsed their visas as they were unable to pay these taxes (which considering they make 1-10 GBP a day and Saudi Arabia had been their home for decades was a very reasonable action) and lived illegally in these areas as landlords cared not a whit for documentation. Destroying these areas and making them have to move to more developed areas where documentation is mandatory for securing housing is an easy and cruel way of flushing them out and removing them from the country. This is most evident in their targeting first of areas with huge immigrant populations, such as Ghulail and Qarantina. In their first attempt to expand these demolitions outside of Jeddah, they demolished a huge ‘slum’ in Makkah with 300 houses that was host mainly to Burmese immigrants.

Finally, the Saudi regime is planning to build government owned housing projects in a lot of these areas and ‘nationalise’ a large part of the real estate market further centralising power in their hands. This gives them a huge boost in income as housing close to a million people in one city alone where you have artificially raised the rent prices would give them a huge boost in their income. This also allows them to complete their 2030 vision for the creation of “cultural centres” as the government announced it would be creating large museums and art galleries and opera houses in Jeddah in the demolished areas.

Conclusion

The Saudi state has long been an extension of the Royal family. The ruling class of Saudi Arabia used to be two families, the family of Al-Saud (i.e. the Royal family) and the family of Al-Sheikh (the family of religious clerics descended from Mohammad ibn AbdulWahab). Under Mohammad bin Salman (MBS) the Al-Sheikh family has been sidelined and the Royal family been purged of any pretenders to power except himself and those that support him. He has aggressively put into practice centralisation policies that build up his power making both the Saudi working class and the immigrant working class carry the can. The destruction of historic areas for working class people and the depopulation has created such a deep contradiction between the working people of Saudi Arabia and the ruling class that there is widespread discontent in a way that there never has been before. Trade unions and political organising are illegal in Saudi Arabia, but it is without question that these things are sorely needed and if they come to exist will be hugely welcomed by the people. There is, for the first time in ages, hope that the working people of Saudi Arabia as a whole want change and are ripe for successful organising. To quote the often brilliant Gamal AbdulNasser:

“Is the reactionary ruler in Saudi capable of suppressing the hopes in the hearts of thousands of young people in the Arab Peninsula? Never. The reactionary ruler in Saudi is incapable of achieving this.”

To allow the conditions for social revolution to flourish and be possible, we must work to force our governments in the West to think twice about keeping relations with despots and tyrants that the House of Saud produces. We must force them to reckon with the countless abuses of humanity that the despotic regime has produced and continues to produce. As long as the House of Saud enjoys the protection of the Western powers, it can continue to oppress its people and its revolutionaries with no regard for consequence. It draws its legitimacy and power from our governments. To defeat the beast, you must sever its limbs. Only then can you sever its head.

Saad Yaqub