The Berlin Wall may have come down in 1989, but that did not mean that Germany was a reunited country. The German settlement was still one that echoed the conclusion of the Second World War, and as a consequence the Soviet Union – and later Russia, for a time – still had a vast array of forces deployed inside East Germany.

Nevertheless, German reunification was an inevitability. The only question was what terms the Soviet Union would accept for the creation of a European superpower inside the NATO alliance, allied directly with the United States, Britain, and France – and one that had ravaged the territory of the USSR not once, but twice, in the same century.

This final negotiation was probably the last time that any country took the Soviet Union seriously. The Soviets had the right to be taken seriously, but right rarely means anything in international relations. What usually matters is might, and that was something the Soviet Union had in spades. The Western Group of Forces, the USSR’s mightiest military assembly – even in spite of Gorbachev’s catastrophic defence cuts, was still probably the strongest grouping of ground forces around the world. Five full Soviet Armies sat in East Germany, and only by negotiation, or outright nuclear war, would NATO be able to dislodge them.

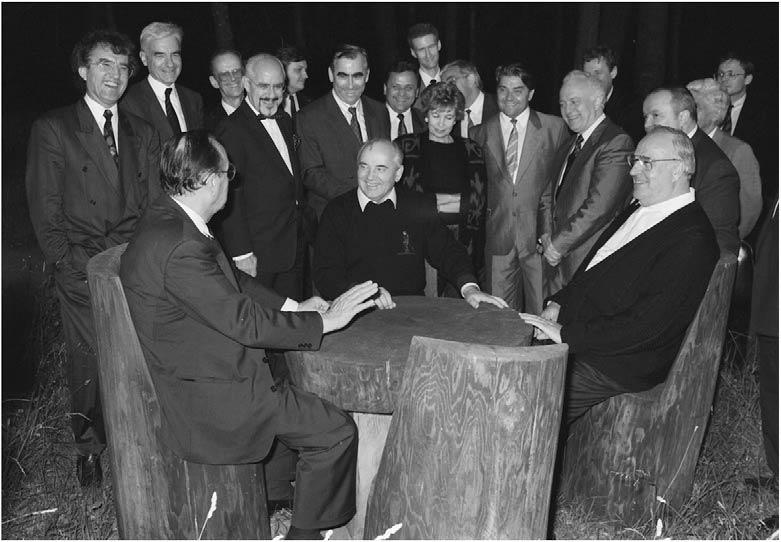

Declassified American archives reveal the various offers made to the Gorbachev in 1990. These archival materials suggest a deep and defining series of assurances made to the Soviet Union about NATO expansion.

On January 31 of 1990, West Germany’s Foreign Minister made it clear in a public speech that NATO should rule out an eastward expansion. The next month, negotiations continued. The United States offered two proposals to the Soviet Union – United Germany outside of NATO, or a United Germany inside NATO with, in the words of American Foreign Secretary Baker, “not one inch eastwards” of NATO expansion. The Soviets accepted either option.

The day after, German Chancellor Kohl told Gorbachev that he thought NATO should not expand.

In April of the same year, British Foreign Secretary Hurd met with Gorbachev and re-affirmed the importance of the principle of retaining NATO’s existing size and sphere in exchange for German reunification. A month later, Baker met with the Soviets again and told them yet again that the post-unification Europe would not have ‘winners and losers.’

The French were not quite as keen on retention of NATO, and admitted to their Soviet counterparts their desire to create conditions favourable to Soviet security. Even Thatcher met with Gorbachev and told him the same thing, that the post-unification political landscape would be one in which Soviet security was “assured.” At this point, the nearest NATO forces in Europe were still a thousand kilometres from Soviet territory.

It is important to remember that at this point in history there remained in East Germany more than four thousand Soviet tanks and seven hundred combat aircraft. These negotiations were made between almost equivalent partners for the resolution of a peaceful Europe in which Germany could be united.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Russia inherited these guarantees. How could it not? It inherited the vast array of military forces in East Germany, which was Russia’s collateral against NATO betrayal – these units left in 1994, not in 1990 or 1991. Russia retained Kaliningrad, which was a post-war territorial transfer from Germany. Russia retained its seat at the UN Security Council. Russia’s immediate security interests were, and are, the same as the Soviet Unions since they are determined essentially by geography.

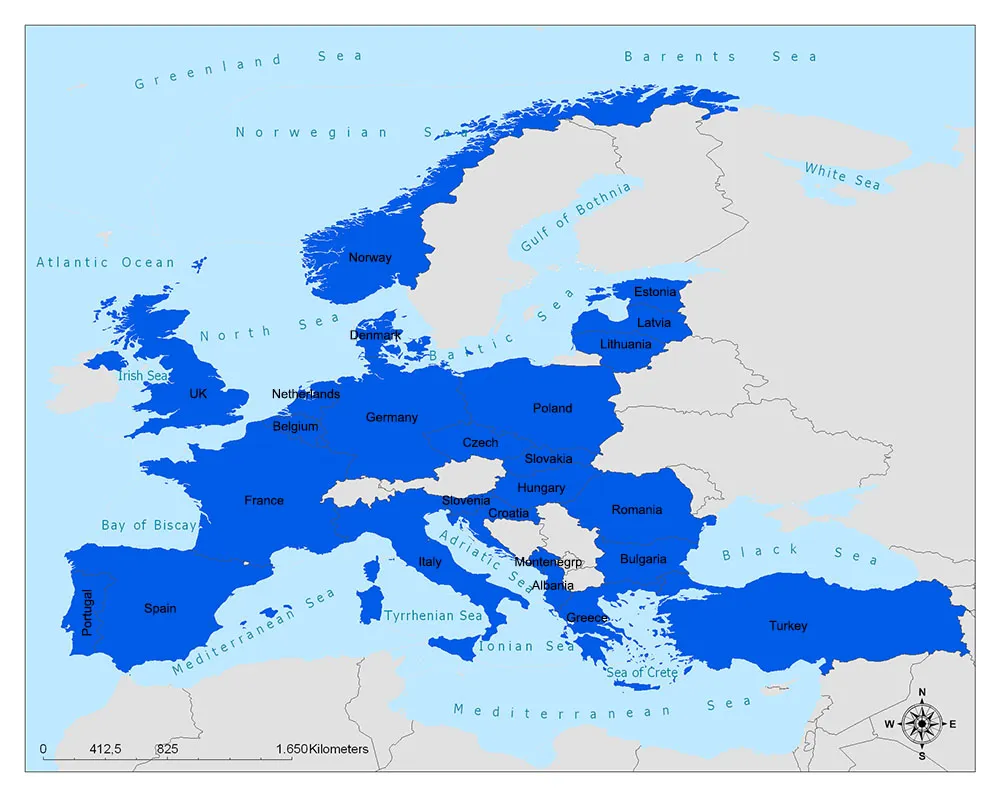

All went well for nine years, until Poland, Czechia, and Hungary were admitted to NATO. In an interview with the Financial Times shortly after, Putin repeated that Russia was “concerned over the process of NATO expansion” because NATO remained a “military bloc with all the threats that this involves.”

2004 saw the largest expansion in terms of territorial size. The three Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined alongside Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia and Slovenia. NATO was now less than two hundred kilometres from Saint Petersburg and the Russian border was now far more exposed than the Soviet one had been in 1941. Only Belarus and Ukraine remained neutral.

Ukraine! How can we forget. In 1994, Russia, Great Britain, and the United States agreed in Budapest a series of measures to support Ukrainian nuclear de-armament, since Ukraine had inherited a relatively large stock of Soviet nuclear weapons. The Budapest Memorandum essentially guaranteed the neutrality of Ukraine. Yet in 2004, despite all historical assurances and the text of the Budapest Memorandum, American and European finances poured in to support Presidential candidate Viktor Yushchenko. Billions of dollars from the State Department and USAID have been spent in Ukraine building a political movement to separate Ukraine from Russia.

Most of this context is lost in the current discussion, which centres around Crimea and Donbas. The facts escape childish analysis of whether Putin is a dictator, or a murderer, or whatever – we support Saudi Arabia’s vicious war in Yemen and we support Israel’s bombing of hospitals in the Gaza strip and so on – but on the simple facts that we promised Russia, in exchange for allowing the unification of Germany, that we would not expand to her borders.

Now our tanks sit on the Russian frontier and we say that Russia is the aggressor. The left is often accused of supporting any country that is opposed to Britain, but the fact is that Britain makes itself opposed to other countries. The left is often accused of siding with Britain’s enemies, but Britain only has enemies because our government keeps making them.

The hostile situation with Russia is all of NATO’s making, and now that we sit on the brink of war with a nuclear armed state. It’s difficult to see exactly what security we have gained from it. Britain is an island – if we wanted to defend ourselves and our interests, our warships and aircraft would patrol the shipping lanes required to feed, clothe, and warm our people. Instead, our armed services are deployed on the frontiers of foreign countries, countries to whom we made promises and guarantees of peace, security, and dignified relations.

There are people who think that Britain’s job is to police the world. These people believe that human rights abuses which happen abroad – and they do happen in Russia, very routinely – are the business of Britain’s armed forces. This mad hypocrisy is nothing more than a fever dream. Our country has no grounds on which to lecture others on human rights when it has been complicit in setting the Middle East alight. More than this, foreign posturing does not make our own society more free or fair. The only people in our country who benefit from war with Russia are the people who profit from making weapons.

We can’t let those people drive our country towards war. The best demonstration that Britain is committed to peace is for our country to leave NATO, the military arm of American imperialism – and to do it before our own country’s security is threatened by this insane rush to war.

Matt Cox, is a member of the YCL’s West and North Yorkshire branch