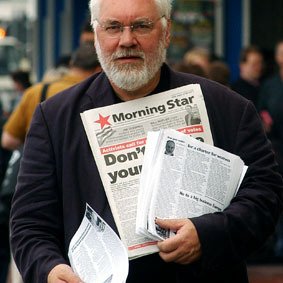

The Labour Party’s stated intention to campaign to keep partition must be ignored — the British working class will find it’s strength in giving the Irish people the right to choose their future, writes Nick Wright. This article first appeared in the Morning Star.

Keir Starmer has stepped into the politics of partition in Ireland with a visit to meet party leaders along with an array of cops and community groups, school kids and, most probably, spooks.

He dressed his substantive support for the Northern Ireland protocol with a diversionary attack on Boris Johnson’s mendacity – as if anyone, on this issue or any other, was surprised at the prime minister’s fully flexible relationship with truth and consistency.

Labour’s barely subliminal positioning on Northern Ireland is the contradictory message that under his leadership, notwithstanding the blanket support for the protocol, Britain would be more accommodating to unionist sentiment than Johnson – whose commitment to the Brexit compromise reached with the EU’s leaders entails a clear willingness to see the Irish border run under the Irish sea and Ireland as a whole to emerge as a more cohesive and distinct economic entity.

This is where the continuing division in ruling-class opinion over the global orientation of British capital continues to wrongfoot Labour.

BBC Northern Ireland put the inevitable question to Starmer on what his position would be if and when a referendum on Irish unity were to take place.

You would think that a Queen’s Counsel might have anticipated the question and – given the delicacies (and crudities) of politics in the partitionist state – found a formulation which conformed to the diplomatic niceties and careful evasions of the Belfast Agreement.

Nope. Starmer said: “I personally, as leader of the Labour Party, believe in the United Kingdom strongly, and would want to make the case for a United Kingdom strongly and will be doing that.”

This was preceded by the statement, made meaningless by his explicit unionist stance, that “the decision, in the end, is for the people of the island of Ireland.”

So it is. And so it will be.

Bear in mind that the granting of a referendum is, under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement, exclusively in the gift of the British government and that Britain is committed by this international treaty to hold the ring.

In fact the Good Friday Agreement stipulates “rigorous impartiality” by the British government in any reunification referendum mandated by the peace deal.

Starmer knows the North very well. Indeed, he has made reference to his time there as an adviser to the Northern Ireland Policing Board and said that this influenced his decision to go into parliamentary politics.

As for the niceties of the protocol, he was shadow Brexit secretary for three years and the principal architect of Labour’s abandonment of its commitment to respect the referendum result.

That this is now completely negated by official Labour’s fiercely policed silence on Starmer’s role in identifying the party with the electorally disastrous second referendum position adds to the confusion of those Labour supporters who then, and now, retain illusions about the nature of the neoliberal EU and thus are confused by Starmer’s apparent volte face in now backing the EU’s very bourgeois Brexit deal with Boris Johnson.

It is probably true, notwithstanding a sotto voce partitionist campaign for Labour to start organising in the Six Counties, that most sensible Labour sentiment favours a united Ireland.

These two aspects of Labour’s present day positioning demonstrate just how integrated into the policy ambit of Britain’s ruling class is this Labour leadership, and how this is pursued without a second glance at where actual Labour opinion lies.

Unionists in the north of Ireland were ever the plaything of the Conservative Party.

When, before, during the first decades of the 20th century it became clear that Irish national aspirations could not be easily met within a multinational British state, one attempt after another was made to secure a form of Home Rule that would keep Ireland as a whole within the ambit of the British empire.

In 1912 the then Liberal imperialist Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, was refused permission to speak at Belfast City Hall and instead was forced to argue the case for Home Rule in a muddy field and then evade muscular Unionists to make his escape from the Irish mainland via Larne to Britain.

In the interregnum, before the Home Rule Bill could go before Parliament, the Tory leader Andrew Bonar Law seized the initiative and told a display of 100,000 of these same muscular Unionists that “when the crisis is over men will say to you . . . you have saved yourselves by your exertions, and you will save the empire by your example.” This made clear to the loyal colonials the role British imperialism had then allocated them.

For the colonial power the wedge issue was the partition of Ireland with six of the counties of Ulster excluded from Home Rule.

As this emerged the local unionist response to the passage of the Home Rule Bill was to subject the North to a storm of sectarian violence with Catholics driven from the shipyards, linen mills and engineering works. Hundreds died.

And, if Home Rule was British imperialism’s concession to Irish nationalism, partition was not just a concession to local Unionist sentiment but more a device to ensure its domination over Ireland as a whole.

As Northern Ireland’s strategic importance to the British empire declined over the post-second world war decades the mechanisms and machinery of the European Union became more important for maintaining imperialist hegemony over the island of Ireland.

It is the belated recognition by Unionists in the North – as British capital reached a new accommodation with the main European powers – that their increasingly fragile pyramid of local power is collapsing that is the motor of the present political crisis in the North.

Partitionist thinking is, of course, still deeply embedded in the politics of the North. Its crudest expression resides in those circles of irredentist Loyalism most invested in sectarian posturing.

Edwin Poots’s brief tenure as DUP leader showed just how clearly this is no longer a sufficient guarantee of Unionist domination over the machinery of local government and may not be enough even to secure a perch in the devolved administration. There is no iron law which says that an explicitly Unionist political formation will occupy either the first or second positions in a Stormont election.

Meanwhile the flight of “respectable” Unionist voters to the Alliance Party becomes more marked as Unionism struggles to stake out a credible position. Unionism’s historic sponsors increasingly regard its local standard bearers as an obstacle to the greater goal of unimpeded profit seeking.

While Jeffery Donaldson worries about the deal with the EU as “the greatest threat to the economic integrity of the United Kingdom in any of our lifetimes” the significant movers and shakers are more invested in the mobility of globalised capital.

Beyond the ever narrowing circles of Unionism the partitionist mindset finds a more diffused role in still seeing solutions for the problems of the North within a British context. At its clearest this is expressed as a desire to privilege economic links across the Irish Sea rather than just down the road.

This may cause Boris Johnson some passing troubles in keeping his MPs in line but it doesn’t begin to divert big capital which regards traversing borders as merely the cost of doing business. The local obsession with this issue fails to exercise decisive traction this side of the Irish Sea.

What does this mean to a working class in Britain that is today reconstituted as a plurinational class of diverse national origins and increasingly homogenised as a multiracial social formation with shared and distinct class interests that do not coincide with the interests of our ruling class?

It cannot be neutral or indifferent or be distracted by constitutional games played by Starmer.

The working class as a whole, and the organised labour movement in particular, needs to side with Irish democracy.

Every step the British working class takes along this road deals a blow to partitionist thinking and to the historically redundant forces in Ireland that stand with reaction. In doing so it takes steps towards a complete break with the ideological hegemony that binds the present day Labour leaders to the manoeuvres of our ruling class. Equally importantly it sends a clear signal to all those in the North, including in the local labour movement, still ruled by partitionist reflexes which make a distinction between British and EU imperialism as if these are entirely separate phenomena.

For all of us on both sides of the Irish Sea it is important to keep a weather eye on the shape shifting nature of imperialism the better to avoid becoming entangled in its machinations.

In analysing the developing imperialist stage of capitalism – in the year of the Irish Rising – Lenin warned against “forgetting the conditional and relative value of all definitions in general, which can never embrace all the concatenations of a phenomenon in its full development.”

The “Irish Question” is at its heart a democratic question that the working class in Britain must finally grasp for it is central to its own social emancipation. Britain has no right in Ireland. It has no right to determine when and how the Irish people express their desire for national unity.

It is time to go.

Nick Wright