This summer marks the 640th anniversary of the 1381 English uprising, often known as the Peasants’ Revolt

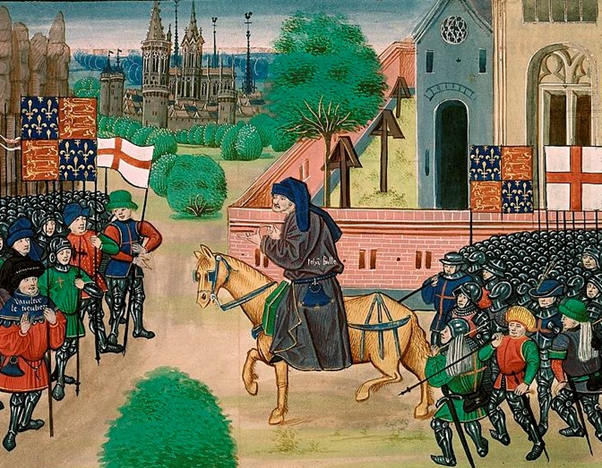

The uprisings in the south east have become the most famous. On their arrival in London, the (largely) disciplined rebels selected political, legal, and ecclesiastical targets associated with the ruling class. Remarkably, rebels managed to get into the Tower of London and decapitate some of the most powerful people in England, including the Archbishop of Canterbury (and Chancellor of England), Simon Sudbury. Elsewhere, rebels negotiated with Richard II and their demands included the end of serfdom and the removal of the clique of royal advisors. But Wat Tyler and the Kentish rebels later pushed for more, demanding from the king an overhaul of the law, church, and aristocracy. In the confusion that followed, Tyler was wounded fatally while Richard started the process of ending the revolt, first by pacifying the shocked rebels and soon followed by the inevitable trial and executions of leaders, notably the priest John Ball on 15 July 1381.

The uprising was driven by class conflict. The catastrophe of the Black Death of 1348/49 led to a labour shortage which, on the one hand, meant that labourers were in a position to make new demands and seek new opportunities; on the other, however, the ruling class tried to cap wages and keep traditional serfdom in place. Longer-term tensions and discontents were exacerbated by the introduction of new taxes, the most infamous being the poll tax of 1380. But the uprising that followed was not just peasants, at least not in the sense we popularly imagine rural workers—rebels included local officials, lower clergy, Londoners, and (escaped) prisoners among their ranks. Their demands could accordingly involve ending serfdom, concerns about social mobility, or simply settling personal vendettas.

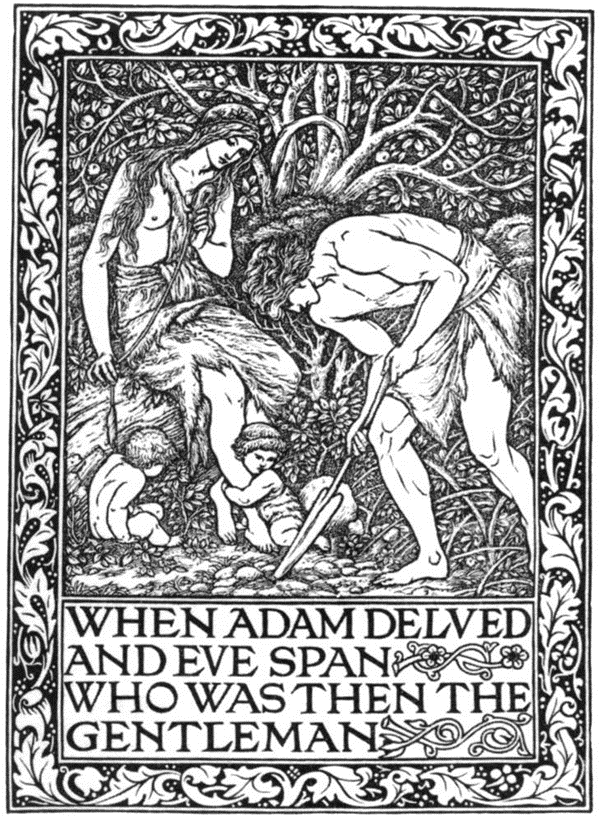

Articulation of discontents came from Ball. Ball long had a reputation as a popular priest, constantly in trouble with the church authorities for his criticisms of them and the lords for their exploitation of labourers. Ball looked to a new social order in England freed from archbishops, the aristocracy, and corrupt priests, and with Ball himself to be placed in charge of English religious matters. Ball became famous for his couplet, “When Adam dug and Even span, who was then a gentleman?” We should understand this sentiment in its fourteenth-century context as involving a new hierarchy which would serve the interests of peasants and labourers. Ball and other rebels believed that this new England would involve holding the resources of the land in common which, in practical terms, likely included full access to game in woods, fields, and waters.

After his death, Ball would be vilified by historians, poets, and theologians of the ruling class in a smear campaign that lasted 400 years. Ball was presented as evil, satanic, heretical, and a mob leader—in other words, he was seen as a seditious threat. But under capitalist transformation and with serfdom increasingly a thing of the distant past, Ball’s reputation was rehabilitated by the end of the eighteenth century. Even hostile establishment figures like the philosopher and historian David Hume had to admit that some of the rebel demands and Ball’s sentiments about human equality were not unreasonable.

The aftermath of the American and French revolutions, and the English radicalism of the 1790s, provided a fitting context for the full rehabilitation of Ball. The silversmith and historian John Baxter, for instance, saw Ball as a heroic defender of ancient English liberties and rights to the land. Baxter also challenged the dominant histories of the ruling class over the previous 400 years: rather than call Ball “a seditious preacher,” he would instead refer to him as “a true philanthropist.”

The most influential work to emerge from this period was not initially published. In 1794, the young Jacobin radical Robert Southey wrote his dramatic poem Wat Tyler. Despite the title, Ball features more prominently than Tyler and is presented as a saintly preacher of equality, justice, and the reclamation of lost rights. Here, Ball reflects on revolutionary violence and how bloodshed is inevitable collateral damage when the oppressed are freed from the demands on their labour as they strive for a better world.

Southey later gave up on his younger radicalism and by the time he became Poet Laureate in 1813 he too was part of the ruling class he had once castigated. But Wat Tyler remerged in 1817, pirated and distributed widely by his enemies. Unfortunately for Southey, Wat Tyler became the most influential presentation of the revolt for much of the nineteenth century, including being a favoured text among Chartists. Chartists also put on popular theatrical performances of the play, sometimes to raise funds for political prisoners. But they also developed their own interpretations of, and lectures on, 1381 including the idea that Ball and the rebels represented lost English liberties which allowed them to develop influential ideas of an English identity grounded in political and economic struggle rather than dominant nineteenth-century understandings of English and imperialist British identity grounded in race and ethnicity.

The rehabilitation of Ball and 1381 continued with demands for constitutional reform, working-class representation in Parliament, and improved conditions for workers. Some understandings of Ball were reformist, presenting him as an advocate for non-violent political change and the acceptable precursor of working-class demands in the nineteenth century. This romantic tradition continues to this day, particularly among left-leaning liberal journalists or (as a rule of thumb) whenever Ball turns up close to mainstream parliamentary politics.

However, there is another reading of Ball and 1381 which was more oppositional in its attitude towards capitalism. The most influential socialist and revolutionary understanding came with William Morris’ A Dream of John Ball, first serialised in 1886–1887. Here, in story form, Morris developed a Marxist understanding of human history and used Ball as a way of explaining the transformation from feudalism to capitalism and then to socialism and communism. Despite the failure of the 1381 uprising, A Dream of John Ball sees Ball’s dedication and sacrifice as a revolutionary example for the present and what is needed to help bring about socialist transformation. As the character of the Man from Essex (effectively Morris himself) says in the story, “I pondered…how men fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.”

A Dream of John Ball had a significant influence on the emerging labour and suffragette movements. Its influence was not restricted to those with more elite education—Harold Laski claimed that he saw copies of A Dream of John Ball in house after house of Cumberland miners. Certainly, liberal and reformist readings of Morris were common enough, but Morris’ historical materialist approach drove some of the most significant developments in the interpretation of 1381 in the twentieth century.

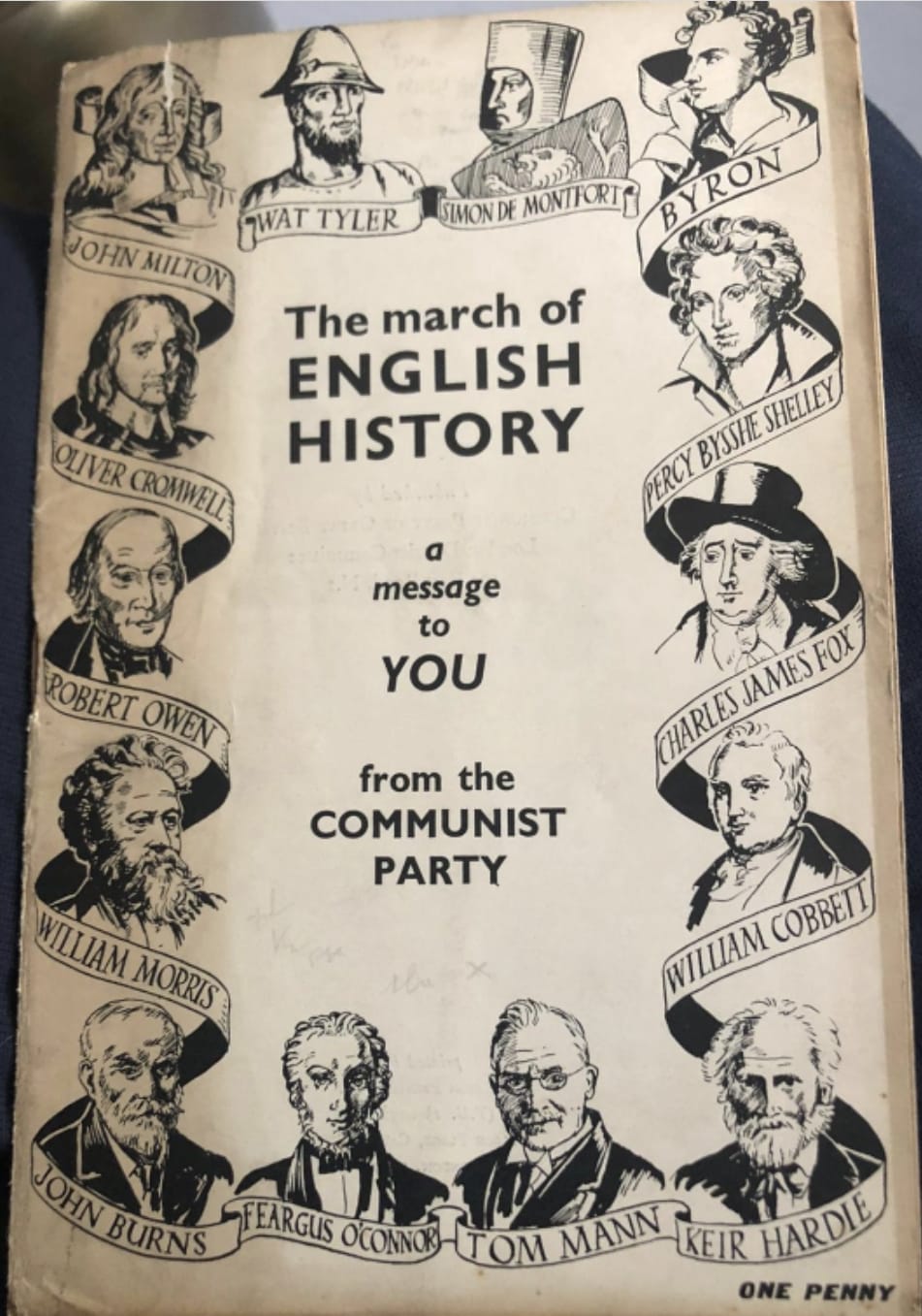

The specifically Marxist tradition peaked in the 1930s thanks to British communists using Ball in Popular Front retellings of English history to counter fascist appropriations of the national past. Left Book Club publications and historical pageants typically placed 1381 as the foundational moment of English resistance to the ruling classes which continued through feudalism, industrial capitalism, and the rise of fascism. Typically, these histories would make connections with international traditions and contemporary struggles, whether with antiracist struggles in America or commemoration of those who died fighting in Spain, such as when the portrait of the communist Felicia Browne appeared at the culmination of the procession for the 1936 “March of History” pageant in Hyde Park.

Interest in Ball declined after the Second World War. It did not disappear, of course, and 1381 came to cultural prominence again during the 600th anniversary of the revolt in 1981. But despite the best efforts of historians such as A. L. Morton and Rodney Hilton, historical materialist readings of Ball became increasingly unfashionable. Certainly, Ball’s memory has been kept alive on different parts of the left, not least regularly in the Morning Star. Elsewhere, presentations of the violence of 1381 and the revolutionary attitude of Ball continue to thrive in non-socialist and non-Marxist novels and documentaries. But this is typical of neoliberal capitalism which absorbs, performs, and tries to neutralise anticapitalism in popular culture.

Yet, crucially, popular culture also keeps the memory of 1381 alive for us and for future generations. It is important that the Morning Star continues to keep its understanding of 1381 alive too, to help illuminate the significance of a history of victories and defeats and understanding of historical change grounded in class struggle. When socialism and the working class in this country have been at their strongest, Ball has been at his most popular. And that is no coincidence.

Professor James Crossley, is author of the forthcoming book, Spectres of John Ball: The ‘Peasants’ Revolt’ in English Political History, 1381-2020, and runs the website www.johnball1381.org . A shorter version of this article first appeared in the Morning Star.