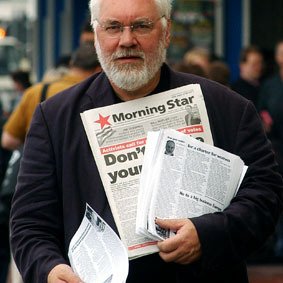

Starmer and his advisers are eager to address the working class as a ‘patriotic’ identity, rather than an economic group that will support progressive policies proposed by people like themselves writes Nick Wright. This article first appeared in the Morning Star.

Labour goes into the Batley and Spen by-election with high anxiety. The retiring Labour MP, the screen writer and actor Tracy Brabin, was elected in a surge of sympathy and solidarity following the murder by a far-right assassin of the previous Labour MP Jo Cox. She built on a solid 17,506 votes in the by-election to win 29,844 votes in the 2017 Corbyn surge.Now Brabin has won a convincing victory in the election for mayor of West Yorkshire and is compelled to resign as MP.

There is the usual squabble about who should be the Labour candidate. The Labour hierarchy have imposed Cox’s sister Kim Leadbeater, who has been hastily enrolled in the party and “selected” in clear abandonment of any pretence that the rules for selection — which entail candidates having a solid period in membership — need are followed.

But this is overshadowed by serious doubts that Labour can retain the seat. The party’s continuing disarray in the aftermath of Starmer’s botched shadow cabinet reshuffle is a sign that the headquarters clique surrounding the leader is still seriously deficient in strategic thinking and tactical flexibility.

The numbers look distinctly unpromising. In the 2019 general election Labour’s vote dropped by 12.8 per cent to 22,594 votes or 42 per cent. A local Brexit breakaway won 12.2 per cent and Ukip proper 3.2 per cent. Labour needs to build on its vote share and total numbers if it is to stop the Tories cannibalising its Brexit rivals.

The Hartlepool disaster was not simply the consequence of Labour’s post-2019 errors or even an astoundingly unwise choice of an unconvincingly repentant Remainer as candidate but more the product of flawed thinking and bogus theory by Starmer’s top team.

The long afterlife of Labour’s Brexit blunders sets the broad context for Labour’s continuing problems but it is not the full explanation for the disconnect with what should be its working-class electoral base.

It is not simply votes haemorrhaging towards the Tories as the principal repository of free-floating Brexit opinion. In fact a big proportion of voters are simply turned off by Labour’s current line-up of people and its policy vacuum and have joined that always substantial section of working-class voters who — in the absence of policies which address their daily problems — simply see no compelling reason to vote.

The conventional assumption that by-elections are opportunities to punish the sitting government for its failures looks like being supplanted by a new phenomena. On present form by-election voters are more likely to use the occasion to emphasise their continuing disapproval of Her Majesty’s loyal opposition than punish the Prime Minister.

In the latest YouGov opinion poll the Tories are on 46 per cent, Labour on 28 per cent, with Lib Dems and Greens vying for third place on 8 per cent and others collectively at about 9 per cent.

Starmer is proving even less popular than his party. While Labour lags 18 points behind the Tories, Starmer is a full 21 points behind Johnson in the polling for who voters think would make the best premier.

This tells us as much as we need to know about the judgement of the people who backed Starmer in his leadership bid on the basis that under any other leader than Jeremy Corbyn Labour would be 20 points ahead.

Of course, it is not the real Starmer who stands before the electorate. It is a confection. And the words that are ascribed to him are the product of his closest advisers.

They represent an exercise in group think in which a common set of traditional right-wing social democratic ideas are twinned with a new orthodoxy which pays lip service to a materialist understanding of how Britain’s class structure is changing.

But instead of a springboard to a fresh thinking about policies that tackle the real life problems of working people this is married to a warmed-over neoBlairite strategy that takes a mechanical view of how working people think and joins it with a new version of the triangulation techniques which destroyed Labour’s class appeal.

At the root of Labour’s continuing and catastrophic decline is the fruitless search for a middle ground which Starmer’s advisers think is now reconstituted around “a new working class.”

Starmer’s policy chief Claire Ainsley argues — correctly enough — that the way class has been reconfigured is important in shaping the party’s political appeal.

On one hand she argues that most people identify as being working class, but that no party can confidently claim to speak on their behalf.

At the same time she says: “There is still a working class in Britain today, but it is different to the one that has gone before it.

“It’s multiethnic, it’s much more diverse. It doesn’t answer to the label ‘working class’ necessarily.”

A patina of original thought is given to these contradictory notions by a sleight of hand in which the Marxist understanding of class is reduced to a simple formula in which “the working class” is applied simply to people who work in what she calls “traditional working-class jobs such as manufacturing, which is actually quite a small part of the population now.”

Her concept of this “new working class” is people who are living on low to middle income, “who might be doing jobs perhaps in the service sector, like retail, catering or hospitality.”

Completely absent from this approach is the idea that working-class political consciousness is shaped not only by the position workers occupy in the class structure but by policies, the experience of collective struggle, leadership and ideology. Politics, in fact.

And it was precisely this human factor — exemplified by enthusiasm for the party’s manifesto and its leadership – that created Labour’s 2017 surge.

In his first speech to the online party conference as leader Starmer asked the host of 2017 Labour voters who abandoned Labour in 2019 to “take another look at Labour.”

“We’re under new leadership, we love this country as you do,” he said.

In a few words he weaponised the Tory trope that the mobilisation that achieved Labour’s highest vote for decades, that spoke for the hundreds of thousands in mass rallies and that offered a peace message in tune with the expressed view of a clear majority of British people was lacking in patriotism.

It was a barely subliminal message that Trident missiles, the global projection of force in alliance with the imperial US, a bipartisan foreign policy in the Middle East and an uncritical approach to the blood-soaked history of slavery, exploitation and empire were once again the basis of Labour policy and that this notion of flag-waving “patriotism” was embraced by Labour.

It is as if they hadn’t noticed that in Batley and Spen over a third of the population have family roots in countries where the horrors and humiliations of colonial rule are still a living memory.

The new Labour candidate will be judged against exacting standards. There is a media narrative being woven around Cox’s death but the martyred MP’s commitment to an uncomfortably Blairite version of “liberal interventionism” will resonate discordantly among the one in five Muslims who make up the electorate.

Justice for Palestine has been a local issue for a long time. Indeed, during an earlier Palestine solidarity protest, the then Labour MP Mike Wood headlined a local rally organised by Friends of Al-Aqsa Dewsbury & Batley branch.

But the tell, the linguistic clue to the new Labour leadership’s alienation from the people and from much of the party itself is present in that “we” that — in its utterance — signified the absolute gap between what Westminster Labour has become, what the Labour Party is still and what the present-day working class looks and sounds like.

With very few exceptions Labour’s elect are drawn from a milieu a million miles from the lives of working people.

Labour’s existence from the turn of the last century is marked by a precipitate plunge in the number of worker MPs. By the end of the first world war nine out of 10 Labour MPs were manual workers. By the end of the second world war it was down to 41 per cent falling to 28 per cent in 1974 and 9 per cent by 2005.

There are about 150,000 lawyers in Britain. In Parliament, 22 per cent of Tory MPs are lawyers, 13 per cent of Labour MPs and 16 per cent of Scottish Nationalists while Britain’s 10 million plus manual workers (and their families) are represented by just four in 100 MPs.

The picture is a bit more complex than these crude figures suggest since big changes in the character of capitalist production have reshaped the class structure. There are roughly 26.52 million employees and 4.61 million self-employed people in Britain. Official statistics list around 1,000 occupational categories in the labour market.

If you have an idle hour or two run your finger down the lists — from refuse and salvage workers (38K) to pipe fitters (13K) or the 214,000 childminders — to see how many MPs followed this kind of occupation before election.

Of course, we can find innumerable example of sell-out Labour leaders of working-class origin as well as parliamentary examples of upper-middle class and even bourgeois siding with the working-class and socialist movement.

This isn’t the point. Shaping a movement that has the aim of working-class political power must be both in and of the people it represents.

Recently the left-wing economist Grace Blakeley — under assault from people who argue that what they think they are is more a signifier of class than what they do — made the point that class has less to do with your accent, where you live, where you grew up, what your parents do, where you went to school.

“Class” she argues, “is a social relationship rooted in production. Either you own resources critical for the production process, or you sell your labour power to those who do. If the latter, you’re either a professional with some autonomy and some assets, or a worker with little of both.”

The continuing failure of Labour’s leadership lies in its inability to speak to the working class as it actually exists and its abandonment of policies that address the real life problems of working people.

It is a failure of class politics.

Nick Wright