As long as communists have existed, the class we seek to topple have told lies about us. The more powerful our threat, the more extreme the lie. The more lurid and sensational the better — like the recent Netflix documentary on the Russian Revolution, which claimed that Lenin kept a 12-year-old maid in a cage while he was exiled in Siberia.

Claims that Cuba had “concentration camps for gays” and Fidel Castro was turning children into tinned food turned out to be similarly untrue, but they got their job done — providing justification for Operation Peter Pan, the Bay of Pigs invasion and hundreds of terror attacks by the Cuban exiles.

The latest red scare propaganda targets China and its autonomous region of Xinjiang. Many people will have seen statistics that refer to “one million Muslims” being held in concentration camps and various other human rights abuses — even “genocide.” It is crucial that the public are aware of where the main allegations come from and gain a picture of what is really going on in Xinjiang.

One man’s word against a nation

One of the most popular infographics, which has received well over a million likes on Instagram at the time of writing, claims one million Muslims are in camps designed to strip them of their identity and brainwash them into supporting the government.

This figure of one million can be traced back to one person, Adrian Zenz — also the first to allege “forced labour” and “forced sterilisations.” Respected Western media outlets have cited Zenz as their main source of information.

The Guardian has been happy to dedicate entire articles to his claims. The Washington Post has published articles where Zenz is the only cited source. The BBC has also referenced him in multiple articles — it reported (with Zenz as its source) that Uighur Muslims were being “forced to pick cotton.” He is objectively the main supply of Xinjiang “concentration camp” information.

Even a brief look at Zenz reveals a clear agenda and a lack of credibility. He is a Christian fundamentalist “led by God [on] a mission against China” who believes “the fall of capitalism would give rise to a rise to power of the antichrist” and that decriminalising homosexuality and the spread of non-violent parenting will put “power behind the antichrist.”

Zenz is also a senior fellow researcher at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, an offshoot of the National Captive Nations Committee described by the Montclair State University website, headed by Grover Furr, as “a front for former Nazi collaborators and extreme right-wing totalitarians, and mainly for the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (Banderist).”

Falsely attributed images

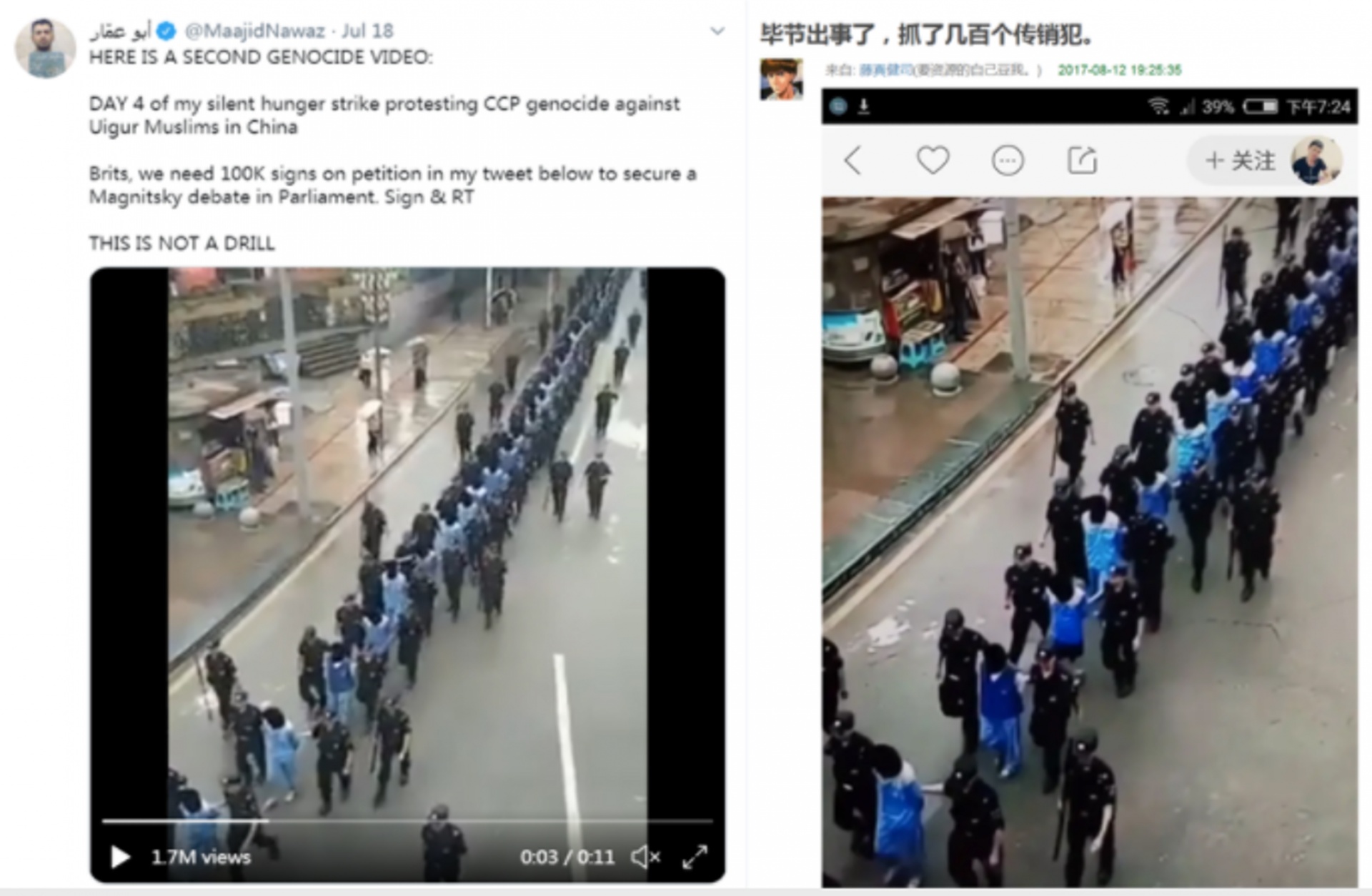

The first screenshot shows the allegation of Uighur genocide by radio presenter and controversial media personality Maajid Nawaz, and the second shows the true origin of the video on Douban. It was actually shot in Bijie, a city in Guizhou nearly 2,000 miles from Xinjiang, on August 4, 2017 and shows a police crackdown on a pyramid scheme, where the culprits were detained and transferred to a detention centre.

Seated in rows in blue boiler suits, this is possibly the most famous image of that is used to imply the existence of concentration camps, slave labour and genocide. Sourced by Qiao Collective back to Luopu County Reform and Correction Centre on April 14, 2017, what has become the face of the “genocide” and still appears in articles by the BBC, Daily Mail, the Guardian and countless other western outlets, was in reality a de-radicalisation talk given to prisoners at a normal criminal rehabilitation facility.

Individual accounts and their problems

The issue with anecdotal evidence is that it is very easy to fabricate. For example, on October 10, 1990, a 15-year-old girl going by the name of Nariyah gave a false testimony before the United States Congressional Human Rights Caucus, picked up by some of the same groups that are pushing the “Uighur genocide” narrative today (Amnesty International, for one).

Nariyah, who was later confirmed to be the daughter of a Kuwaiti ambassador to the US, claimed that she had witnessed Iraqi soldiers take babies out of incubators in hospitals, leaving them to die. The false testimony was then used by George HW Bush as atrocity propaganda to help shift public opinion in favour of the First Gulf War.

Western governments have a long history of presenting individual accounts as objective facts in order to push an imperialist agenda. The US uses anti-China stories to condone trade wars, calls for sanctions, military drills on their coast and to drum up support for territorial conflicts in and around China — Hong Kong, Tibet, Taiwan and now of course, Xinjiang.

It is no surprise that the Xinjiang region has large oil reserves, a recurring feature when US “concern for human rights” turns into backing separatists and insurgents. There are clear parallels between the Nariyah testimony and the atrocity propaganda now being used against China.

What is really happening in Xinjiang?

The destabilisation of the Middle East by the West led to a surge in Islamic terrorism around the world — including China. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (Etim) in Xinjiang has ties to the Taliban and al-Qaida — it sent the so-called Turkistan Brigade (Katibat Turkistani) to join a network of al-Qaida-linked groups fighting alongside al-Nusra in Syria.

Despite this and despite US military officials confirming that they had targeted Etim through air strikes in Badakhshan, close to the border of Xinjiang, the US decided to take them off its list of terrorist organisations on October 20, 2020 — which removes any US penalties for assisting or funding the group.

According to CGTN, “From 1990 to 2016, thousands of terrorist attacks have been launched in Xinjiang, killing large numbers of innocent people and hundreds of police officers.”

In response, China has launched campaigns to crack down on violent extremism, separatism and terrorism with a focus on re-education. The camps were built to de-radicalise Muslims who had been victims of Etim’s ideas — this is the point of the mass mobilisation in the region that has led to false allegations of “genocide,” “forced sterilisation” and “torture.”

The report by the State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China puts the state’s case forward plainly.

“Faced with this severe and complex problem [religious extremism], Xinjiang has upheld the principle of addressing both the symptoms and the root causes in the fight against terrorism and extremism, by striking hard at serious terrorist crimes, which are limited in number and by educating and rehabilitating people influenced by religious extremism and involved in minor violations of the law.

“In accordance with the law, it has established a group of vocational education centres to offer systemic education and training in response to a set of urgent needs: to curb frequent terrorist incidents, to eradicate the breeding ground for religious extremism, to help trainees acquire a better education and vocational skills, find employment and increase their incomes and most of all, to safeguard social stability and long-term peace in Xinjiang.”

At the camps residents are taught Mandarin — the lingua franca spoken by 73 percent of the Chinese population — taught technical skills in order to help them find work when they leave and offered mental guidance to overcome radicalised ways of thinking.

Of course, as is the case everywhere in the world, the severity of a sentence depends on the scale of the crime and the willingness of a person of acknowledge their guilt.

The people in the re-education centres are assessed on how much harm they have been caused, their willingness to receive training and whether they have already completed a prison sentence but might still require further rehabilitation.

The people in the centres are provided with free education and once the trainees reach their expected criteria, they are offered certificates of completion and can leave. Depending on the reason they are there, many are allowed to go home to visit their families once or twice a week.

It is absolutely not a campaign to stop them practising Islam — religious activities are protected by Article 36 of the constitution: “Citizens of the People’s Republic of China enjoy freedom of religious belief. No state organ, public organisation or individual may compel citizens to believe in, or not to believe in, any religion; nor may they discriminate against citizens who believe in, or do not believe in, any religion.

“The state protects normal religious activities. No one may make use of religion to engage in activities that disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the state. Religious bodies and religious affairs are not subject to any foreign domination.”

And despite allegations that the Uighur language is banned in China, made by outlets like Radio Free Asia, in the background of a BBC documentary exploring a centre in Hotan, Xinjiang, Uighur script is clearly visible on the walls — the language is used in “the camps” themselves. Lessons are held in both.

Although only 0.31 per cent of the Chinese population, the Uyghur language is also present on Chinese money.

Trusting China’s account: who does, who doesn’t — and why

Ignored by the majority of Western media outlets is the fact that China invited the UN to investigate the camps. Despite US attempts to prevent the UN from going, they decided to go anyway and found no evidence of mass human rights abuses or genocide.

China has also recently invited the EU and Western diplomats to Xinjiang in order to investigate the continued allegations of human rights abuses; the requests thus far have been refused.

Even the US State Department’s Office of the Legal Advisor concluded after a review that there was not enough evidence to prove the alleged genocide in Xinjiang, which confirms that the decision to apply that label was politically motivated and not evidence-based.

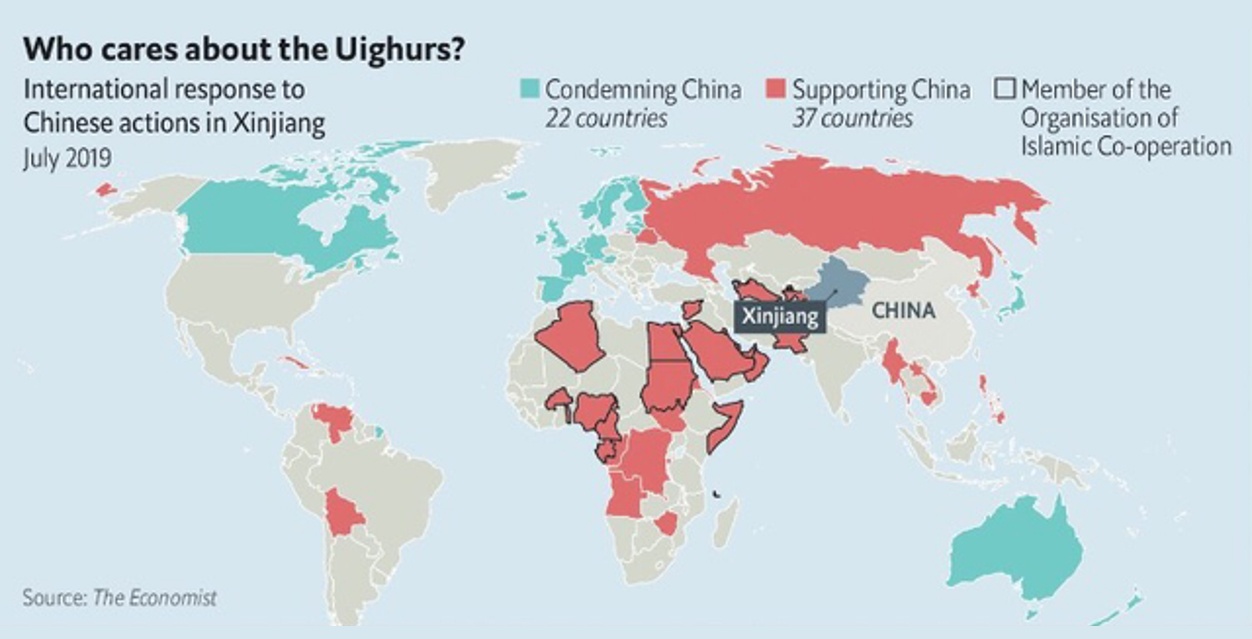

Internationally, support and condemnation of China’s programme in Xinjiang is overtly political. A majority of countries do not condemn it, including most Muslim-majority nations, nor does the Organisation of Islamic Co-operation — who toured the centres and found no human rights abuses; those that support the US line on Xinjiang are the US’s closest allies — Britain and Europe, Australia and so on.

Although many critical reports have implied that they are “shocking exposés” of something China is covering up, no-one is denying the existence of camps in Xinjiang, nor saying that they must be supported without reservation. There may be all sorts of issues that a person could take with the policy and the way it may be being carried out.

However, what people should not engage with is sharing information they have conducted no research into, especially anecdotal accounts. Allegations of “genocide” must be dealt with critically when there is so much evidence that these claims are politically motivated — born out of a desire to isolate and undermine what is now the main rival of the US-led Western bloc.

We cannot ignore the drive to war against China. Fear of speaking out against atrocity propaganda because of its upsetting and controversial nature will only lead to the manufacturing of consent for war. Western intervention led to two million people dying in Korea, 2.4 million people dying in Iraq since the 2003 invasion, three million people dying in Vietnam among millions more elsewhere.

Given the history, given the body count, socialists have a duty to vehemently oppose the idea that our countries should be able to interfere in others; denouncing the false narrative on Xinjiang is now part of that duty.

Charlotte Jones