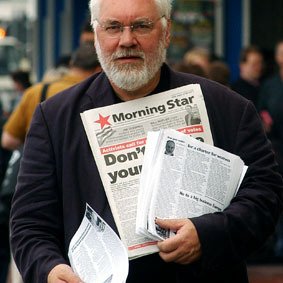

Nuclear weapons are unpopular across the political spectrum, especially in the party Starmer now leads. So why, asks Nick Wright, are these vote-seeking ‘pragmatists’ so hell-bent on keeping them? This article first appeared in the Morning Star.

The Westminster Labour spin on John Healey’s speech last week setting out the current leadership’s position on defence was that it was a shift in tone from the Corbyn period.

That it certainly was. Where Corbyn was widely seen as the personification of anti-war sentiment and stood for a foreign policy approach based on ethical values, the balance of power in the party, in Westminster and in the apparatus, was in inverse proportion to the feeling among the party membership and trade union opinion — and at variance with opinion in the country.

A poll commissioned by CND showed that 59 per cent of the British public support the government signing up to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, including half of Conservative voters and more than two thirds of Labour voters.

This United Nations treaty has entered into force, and makes nuclear weapons illegal for the countries that sign it.

It is not only in Britain, with its distinctive submarine-borne Trident nuclear missiles, that opinion shifts against nuclear missiles, especially when the cost is mentioned.

In Belgium only 21 per cent favour US nukes remaining, in Germany it is just 18 per cent, in Italy 21 per cent and the Netherlands only 32 per cent.

Official Labour’s less than subtle repositioning on both economic and foreign policy over recent weeks is the clearest signal so far that the new leadership regards the years that preceded the 2019 election as an unforgivable error never to be repeated.

Official Labour is with the 9 per cent who oppose a windfall profit tax on pandemic profits and out of step with the big majority in favour.

But it is, and was, over foreign policy and especially among young people that the contradictions are most marked.

The multi-generational sweep of the anti-war movement has hardly changed in the decade that has elapsed since millions marched against the Iraq war, while within this wide spectrum of views a distinct sector has become consciously opposed to imperialism and alert to its every manifestation.

Events of the last few years have taught us that even though a divided Labour Party entered the last two elections under Corbyn still committed to Nato membership and the Trident nuclear strike force, any suggestion that an anti-war prime minister might take office required a full spectrum hostile response. And this predictably came from all the political forces committed to the main precepts of postwar British foreign policy.

A distinctive feature of the British imperial mindset is its constant reappearance on the left.

Where once it was Britain’s civilising global mission today it is liberal interventionism and a wilful blindness to the human cost of Britain’s imperial alliances.

Thus Labour politicians can deplore the Saudi intervention in the Yemen conflict while leaving BAE Systems and the RAF role in facilitating that war unquestioned.

As predictable as clockwork the commentator Paul Mason — who is to Labour’s moving right show what the African Oxpicker bird is to a rhinoceros — chimes in with a wordy tweet to point out that “all wings of Labour supported Nato at foundation.”

And this is true. But then so did the Soviet Union.

Or at least it took the protestations that the formation of the alliance was merely a collective security pact at face value.

In 1954 Soviet foreign minister Molotov floated the idea that the USSR should state its willingness to join Nato.

The Soviets proposed an alternative to Western schemes for a European Defence Community that entailed rearming West Germany. This was something the Soviets — just a decade after the end of the second world war — were keen to prevent.

The Soviet diplomatic alternative entailed German reunification and its neutralisation.

Naturally, the Western powers cold-shouldered Molotov’s collective security scheme.

The initial Soviet proposal that the US be excluded from the proposed European collective security treaty and relegated, along with the other wartime ally China, to observer status was incompatible with the offensive posture of this “North Atlantic” scheme that entailed a massive and continuing US military presence on European soil.

Molotov immediately responded and told the West that the Soviet proposal was open to amendment and the USSR might consider joining Nato.

In their internal discussions the Soviet leadership were quite clear about their strategic aim in defusing the growing confrontation.

In his note to the Soviet Presidium Molotov wrote: “It is necessary to consider another argument deployed against the Soviet proposal, namely that it is directed against the North Atlantic Pact and its liquidation.

“In order to limit the use of this argument against the Soviet proposal the Foreign Ministry considers it advisable that simultaneously with our proposal about the participation of the US in the General European Agreement we should, in the same note, pose, in an appropriate form, the question of the possibility of the Soviet Union joining the North Atlantic Pact.

“Raising this question would make things difficult for the organisers of the North Atlantic bloc and would emphasise its supposedly defensive character, so that it would not be directed against the USSR and the people’s democracies.”

The Western powers were keen to head off a challenge to the proposed European Defence Community and accordingly rejected Soviet participation on the grounds that it incompatible with the scheme’s democratic and “defensive” character.

And to underline the democratic credentials of the new alliance it appointed as its supreme commander General Hans Speidel.

This was a Nazi general who had been stationed on the Russian Front as Chief of Staff to the Wehrmacht’s 5th Army Corps. According to the Federal German Intelligence service he was suspected of being a member of the postwar Schnez-Truppe, the secret illegal army that grouped Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS veterans.

This background stuff is important because the traditional right-wing Labour position — echoed now by Healey — is that the Soviet Union presented an imminent threat of a military attack to overrun Western Europe and that to prevent this the Western states needed a US land-based and nuclear armed presence.

This position had limited traction with the war-weary peoples of Europe. And in Britain, 10 years after the war, the Nato enthusiasts in Labour had to contend with the sense among millions of working people that fascism was only defeated by the alliance of Britain and the US with the Soviet Union and that it was the Red Army that liberated much of Europe.

While the “defence” strategy of the Western Alliance has been grounded in the myth that a Soviet ground attack was under active consideration in the Kremlin, the reality was that it was Nato that continually sought to obtain a strategic advantage while the Soviets wanted a buffer zone of allied socialist states.

This reached crisis point in 1980 when the US proposed siting new Cruise missiles in western Europe — capable of striking deep into Soviet territory.

The existing Soviet missiles sited in Europe had a limited range of 4,500 miles and even the latest had only a range of 5,000 miles that rendered them incapable of reaching targets in the continental US.

Each US nuclear missile had destructive power four times that of the atomic bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Nato planned the deployment of 464 Cruise missiles and 108 Pershing II ballistic missiles to be dispersed across capitalist Germany, Italy, Belgium and Holland in addition to those here at Greenham Common and Molesworth.

This new US deployment changed the strategic balance in that it meant that a “limited” nuclear exchange was possible that did not necessarily entail the exchange of intercontinental ballistic missiles between the USSR and the US — the so-called policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (or MAD).

Europeans of almost all political views soon grasped the idea that cold war strategists were considering a conflict scenario that would reduce much of our continent to a smoking pile of radioactive ruins whilst the North American land mass might escape anything but a disproportionate response.

The consequence was that a mass movement developed everywhere in Nato countries and the balance of influence in Labour changed to directly oppose a key element of Nato strategy.

Much of Westminster Labour’s repositioning today is less to do with reconnecting with its lost voters and more to do with reassuring the significant power brokers in our bourgeoisie and across the Atlantic that Labour in government would not present a threat to the continuity of imperialist foreign policy that Biden is busily re-establishing.

So when Mason confesses that he is “someone who has always argued from the get-go that Corbyn should combine a radical left economic policy with traditional soc-dem positions on security/defence (like Syriza)” it is a frank admission of his overarching loyalty to the present-day imperial project.

The point however is that Westminster Labour’s adherence to the policy of nuclear weapons in general and the deployment of the new generation of US missiles in Europe was frequently at variance with party policy as determined by annual conference.

In the mid 1960s Labour prime minister Harold Wilson simply defied Labour’s policy in favour of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

When the firmly pro-CND Michael Foot became Labour leader in the 1980s he never had parliamentary support for Labour’s conference stance on nuclear weapons even though it was in the election manifesto.

Indeed such was the mood in Labour that Tony Blair fought his first election campaign on a programme of opposition to membership of the European Community and for unilateral nuclear disarmament.

Indeed, I remember him sporting his CND badge at Wandsworth Labour events in the Earlsfield Co-op hall.

Nato’s fan club and numbers of nuclear nutjobs can be found in Westminster Labour and in the party leadership, but among party members and supporters — and among Labour’s voters — a different view prevails.

Nick Wright