Inside a base in the Catatumbo mountains, Oliver Dodd speaks to Comandante Villa Vazquez in the first ever face-to-face interview with a senior figure in the recently re-established guerilla army

DESPITE signing the 2016 peace deal that brought more than 50 years of war with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Farc) to an end, the nation’s establishment, including the right-wing government, have refused to implement the terms of the agreement.

Instead, the state and business community saw peace as an economic opportunity: with the biggest threat to capitalist accumulation out of the way, former Farc-controlled territories have become the veins through which multinational corporations have looked to expand through industries that have a heavy impact on the now-unprotected land and those who live off it.

Mining, logging, drilling for oil, palm-oil extraction, privatisation of fresh water sources, poaching and narco-traffickers have been laying waste to former Farc strongholds, forcing millions of peasants from their homes and into Colombia’s slums, where few jobs and little to no social security awaits them.

At the same time, more than 1,200 social movement leaders, especially trade unionists and ex-Farc combatants have been assassinated by paramilitaries since 2016. Colombian courts have continued the wartime practice of prosecuting left-wing insurgents but not state actors.

The high hopes of the Farc, which announced its reformation as a legal political party under the same acronym – the Common Alternative Revolutionary Force, before renaming themselves Comunes – have so far been dashed, as they have failed to secure any serious land or political reforms as agreed, and, now unarmed, face the pre-existing level of para-state violence.

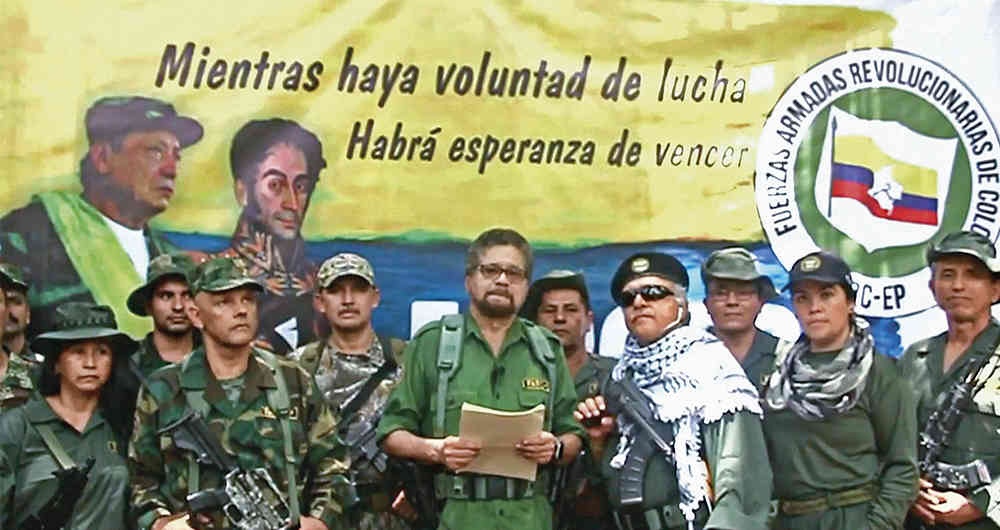

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, on August 29, 2019 scores of historically important Farc leaders, some of whom had suddenly and dramatically disappeared from public life, split from the legal political party, regrouped militarily, and announced the re-establishment of a party that would combine a legal political struggle in the social movements and trade unions, with an armed struggle in rural and urban spaces.

In their Political Manifesto, this faction – known more specifically as Farc (Segunda Marquetalia) to distinguish itself from its predecessor and other ex-Farc combatants who have chosen to continue struggling for the implementation of the agreement peacefully as part of Comunes – declared that it was a strategic mistake to have given up their weapons prior to the implementation of the peace agreement, concluding that this was the only way that the agreement could have been guaranteed in a country that has long been the most repressive in Latin America.

Comunes, which is headed by the Farc’s highest ranking commander when the 2016 peace agreement was signed, Rodrigo Londono, argues that it is imperative that ex-Farc combatants continue to defend the peace agreement as part of a process of establishing national reconciliation and political legitimacy for the left.

But although a clear majority of historic ex-Farc combatants remain active legally as Comunes, the Segunda Marquetalia represents a significant split.

To understand the political situation and the perspective of Segunda Marquetalia forces, I travelled to Colombia’s rural Catatumbo region to observe the re-founded group as they regenerate their political-military struggle and interview one of their leading figures, Comandante Villa Vazquez, who is responsible for the Danilo Garcia Command and is a member of Segunda Marquetalia’s equivalent of a central committee, known as the National Directorate.

As a teenager, Vazquez joined the Young Communist League, a group closely affiliated with the legal Communist Party. When more than 5000 unarmed left-wing activists, mainly from the Patriotic Union party which emerged from the peace negotiations of La Uribe, were massacred by death squads in the mid to late 1980s, he took up arms and has been a member of the Farc ever since.

Many of those killed were butchered using the most gruesome methods imaginable — often working with the military, a favourite paramilitary tactic is to sever the limbs of socialists using chainsaws and machetes before dumping the corpses in the river or leaving them to rot in the villages and towns as a warning.

The slaughter continues: in December 2020, Rosa Mendoza, an ex-Farc combatant, was murdered along with five members of her family, including a daughter only a few months old. On February 13 23-year-old Leonel Restrepo became the 258th former Farc combatant murdered in the “peace” process. The number has since risen to 259 following the killing of Jose Paiva Virguez on February 19.

Vazquez insisted that despite the fact that Farc signatories stuck to the peace agreement and fulfilled their side of the bargain, the Colombian state reneged on the agreement, continued to murder Farc militants and other activists and consequently “committed treason at the expense of the Colombian people, the international community and ex-Farc combatants.”

The commander argued that the Farc and the Colombian people have the right to rebel and renew the armed struggle because the “Segunda Marquetalia are the result of the breaking of the 2016 peace accords by Colombia’s government and oligarchy.”

Pointing to the increase as opposed to decrease of paramilitary killings, Vazquez concluded that “all our hopes were in the agreement, but the agreement was betrayed by the government and other dominant class forces. That is why we had to return to arms. But it is not the Farc who has returned to arms — it is the people themselves. Today, we can say that 60 per cent of [Segunda Marquetalia’s] fighters are new, they are not ex-members.”

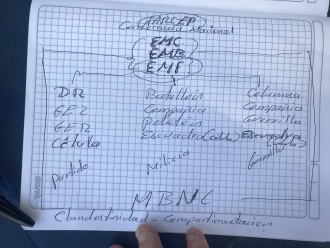

In response to Colombia’s establishment dismissing the Segunda Marquetalia as an apolitical criminal entity, Vazquez described their strategy to me in detail, drawing out a diagram on my notepad. The Segunda Marquetalia combines three key organisational structures as part of its overall strategy: armed guerilla forces, armed and unarmed militia units and an entirely unarmed Partido Comunista Clandestino de Colombia (Clandestine Communist Party).

Guerilla forces are primarily but not exclusively responsible for offensive armed operations against the state and ruling class; the militia are mainly tasked with promoting the group’s objectives within a specific territory, such as a town or village – especially those zones that have been taken by the guerillas; and the Clandestine Communist Party is unarmed – like conventional communist parties, they work within trade unions, social movements, universities and local communities, but must remain covert due to their alignment with Segunda Marquetalia.

Insisting that Segunda Marquetalia is principally a political party as opposed to an armed group, Vazquez said that “Weapons are part of the combination of the ways of struggling and are a guard of ideas” and “it is not that we are going to take power through an armed movement — armed struggle happens because there are no warranties to manifest ideas.”

Vazquez baulked at their characterisation as a peasant rebellion. The three organisational components — guerilla, militia and communist party, he said, reflect the peculiar historical conditions of the class struggle in Colombia.

“Where does the revolutionary struggle develop?” he asked me. “It is developed where the people are, not in the isolation of the jungle but where the masses of people are — and most people today are based in the cities and that is where the revolutionary and guerilla struggle is going to be developed.”

By carrying out key functions of the state in its base areas and strongholds — taxation, security and infrastructure maintenance — the leadership proclaims their organisation to be a legitimate form of government, sustained by a comprehensive political programme and social contract.

Although the group was only re-established on August 29, 2019, Segunda Marquetalia already has a significant base of civilian support in the communities I visited. I watched their troops pass through villages unhindered and saw their members work openly, interacting with the civilians in the streets, even holding public meetings, seemingly unafraid that their presence could be reported to the Colombian military.

A local woman living in a farm within a Farc stronghold, who did not see herself as a socialist or political activist, told me, “The community here prefers the Farc [Segunda Marquetalia] to the police and military.”

“They are always around to help immediately when asked. They are part of us and support us with basic needs in a difficult situation. They also help us to organise the community here.”

However, the recent claims of Colombia’s largest magazine Semana, that they have 5,000 combatants and are supported by Caracas which allows them to systematically exploit Venezuelan territory is clearly inaccurate.

Although it might seem counterproductive for pro-state media to exaggerate the success of its enemies, it serves to justify increases in the already extensive military aid that Colombia receives – as well as giving the United States a pretext for action against Venezuela.

In truth Segunda Marquetalia is a newly formed group and while being able to rely on civilian support in some communities, as a recent breakaway faction, the number of combatants is significantly smaller than the Farc that signed the peace agreement.

Even so, new militants are entering the ranks and committing themselves to the organisation for life, serving under a highly experienced political leadership with decades of struggle behind each of them.

For the government this is a situation of its own making. Unable or unwilling to guarantee the safety of either demobilised fighters or social movement figures who played no role in the civil war, it has provoked exactly this reaction.

Negotiators will be hesitant to trust representatives of Colombia’s state in future peace talks – and Segunda Marquetalia have a lot to bargain with. The taxation of multinational corporations and extractive industries exploiting natural resources, as well as the black market, enable them to feed combatants three meals a day, clothe and arm them with modern weaponry and transport.

They have the money and resources to allow all of their members to dedicate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year to the cause.

And that is where the money goes; the life of a Farc member of any rank, has always been simple – true of all the left-wing Colombian guerilla movements I have studied in the last 10 years I have spent in the field.

I walked with Vazquez through a small farm where the guerillas were growing their own food and rearing livestock; each day they take it in turns to manage the crops and feed the animals, a method of self-reliance that Vazquez was proud of.

Although, he said, “expenses are significant for an organisation like ours, as revolutionaries we cultivate, we invent things such as creating agricultural collectives with the population, we develop economic activities, including producing our own food.”

By the time I had finished my interview with Vazquez and had observed Segunda Marquetalia in their home territory over the period of a week, it was clear to me that the re-founded movement was already growing deep roots.

The failure to implement structural reforms addressing the super-profits of the extractive sectors, large landowners and other capitalists, while refusing to halt the forced displacement of peasants, a major demand of the 2016 agreement, all but guarantees that the organisation will gradually expand.

The Colombian state’s perfidious approach to the peace process as a way to disarm and demobilise the most pressing threat to capitalism, was simply war by other means – and now the Segunda Marquetalia was replying in kind. A spectre once again haunts Colombia: it is the spectre of the Farc.

Oliver Dodd