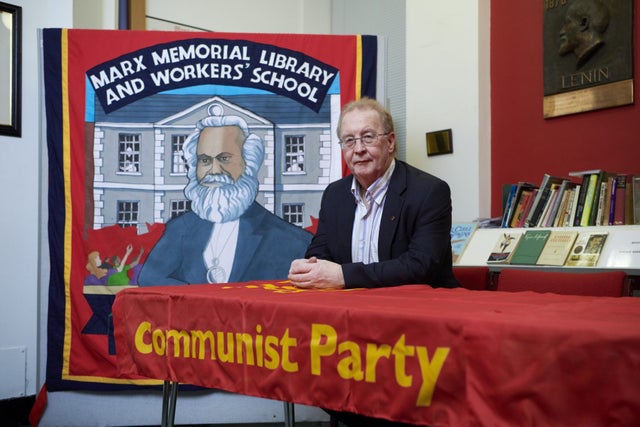

Robert Griffiths, General Secretary of the Communist Party, was invited to speak at the (COVID-19 delayed!) International Scientific and Practical Conference in honour of the 150th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, hosted by the Leningrad Regional Committee of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, last Saturday (17 October 2020).

Challenge carries a transcript of the speech delivered by the CP General Secretary.

Leninism continues to be the Marxism of the era of imperialism. His works such as Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916) clearly set out the economic and political basis of modern imperialism, showing why and how it can survive the passing of formal empires including those of a previous era.

The economic exploitation and the political and military domination of many peoples around the world by a few powerful imperialisms remains the predominant feature of international economics and politics today.

But we can also add aspects of that domination which became more pronounced in the course of the 20th century, such as the cultural imperialism which spreads and reinforces the outlook and values of Western imperialism in general and of United States imperialism in particular.

And, returning to Marx, we also have to highlight today the gathering environmental and climate change crisis which is primarily a consequence of capitalist development. As I summarise in my book Marx’s Das Kapital and Capitalism Today (2020), he laid the basis for the theory of the ‘metabolic rift’ that has opened up under capitalism between human society and the natural world.

Lenin more than anyone else explained how modern imperialism is based upon the fusion between the economic power of giant transnational corporations and the political and military power of the state, to form state-monopoly capitalism.

His State and Revolution (1917) strips away capitalist and social-democratic ideas about the supposed ‘neutrality’ of the state, revealing it as an instrument of class rule. Yet Lenin also emphasised the dual nature of state power in that it combines policies of coercion and consent, with one or other aspect dominating in different circumstances.

Of course, the great lesson for Communists and socialists today, still – and demonstrated by experience in the 20th and early 21st centuries – is that the struggle against capitalist state power has to be approached scientifically.

For the prospect of success, the revolutionary movement has to have a strategy, leadership, a powerful communist party and – in most conditions – a mass movement usually based on alliance of forces led by the working class.

That strategy must be based on, in Lenin’s words, the concerete analysis of the concrete situation – what he called the living ‘gist’ (or essence) of Marxism.

Britain’s Communists have recently updated our party’s strategy, set out in our programme Britain’s Road to Socialism, published earlier this year.

Our platform of economic, social, environmental and cultural policies also contains a section composed of democratic demands. As Lenin argued so convincingly in Imperialist Economism: A Caricature of Marxism (1916), these can play a vital role in preparing the subjective and objective conditions for the overthrow of capitalist state power. They can inspire, educate, unite and mobilise masses of people for demands that can improve their lives under capitalism while at the same time exposing its limitations and distortions.

Lenin, at least, was clear that socialism – the lower stage of communism – must aim to expand the democratic rights of the people, placing these rights on an economic basis which makes them real, drawing the people into the exercise of state power so that those rights are protected and guaranteed.

Several of Lenin’s works on the national and colonial questions underline the ongoing significance of national-democratic and cultural rights. One of my favourites is his essay On the National Pride of the Great Russians (1914), where he points out that every nation has a progressive as well as a reactionary history, and that Communists should celebrate the struggles of their own peoples against exploitation and oppression. In other words, there is such a thing as a progressive patriotism, which is the Communist alternative to national nihilism.

Even in an advanced capitalist society such as Britain, as Lenin recognised, the national question has not yet been relegated to the past. That’s why the Communist Party calls for ‘progressive federalism’, based on the devolution of real powers to the peoples of Scotland, Wales and the regions of England while maintaining working-class and progressive unity and solidarity against the united force of British state-monopoly capitalism.

Left-Wing Communism: An Infantile Disorder (1920) stands as a permanent warning against tendencies in the communist movement to underestimate the battles for democracy, the importance of the electoral front of struggle and of parliamentary politics, and the need for a revolutionary party.

Since Lenin’s day, the international communist movement has passed through different phases – the Comintern, Cominform and then international meetings interrupted for a period after the defeats and counter-revolutions of the early 1990s.

The challenges of today – for peace against imperialist aggression and a new Cold War against China and Russia; for national and international action against global warning – now require a more closely coordinated international movement of communist and workers’ parties, inspired and guided by the living works of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

Robert Griffiths

General Secretary

Communist Party