Today, October 9th, marks the anniversary of the assassination of Argentinian revolutionary Ernesto ‘Che‘ Guevara, which took place in Bolivia, 1967. Che had secretly and mysteriously left Cuba a few years earlier, renouncing his official titles and his honorary Cuban citizenship, in order to help fight and progress other revolutions around the world.

However he met his end after being captured by Bolivian Special Forces, with help from the CIA. After a failed interrogation, a nervous soldier was sent in to kill him, stalling in doing so, to which Che famously responded with:

“I know you are here to kill me. Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man.”

Thus, the legend was born and Che was immortalised as a martyr for revolutionaries and rebels around the world. For they had killed a man, but in doing so they had ignited the flames of his ideas and the ideas of those who had shaped and informed his actions.

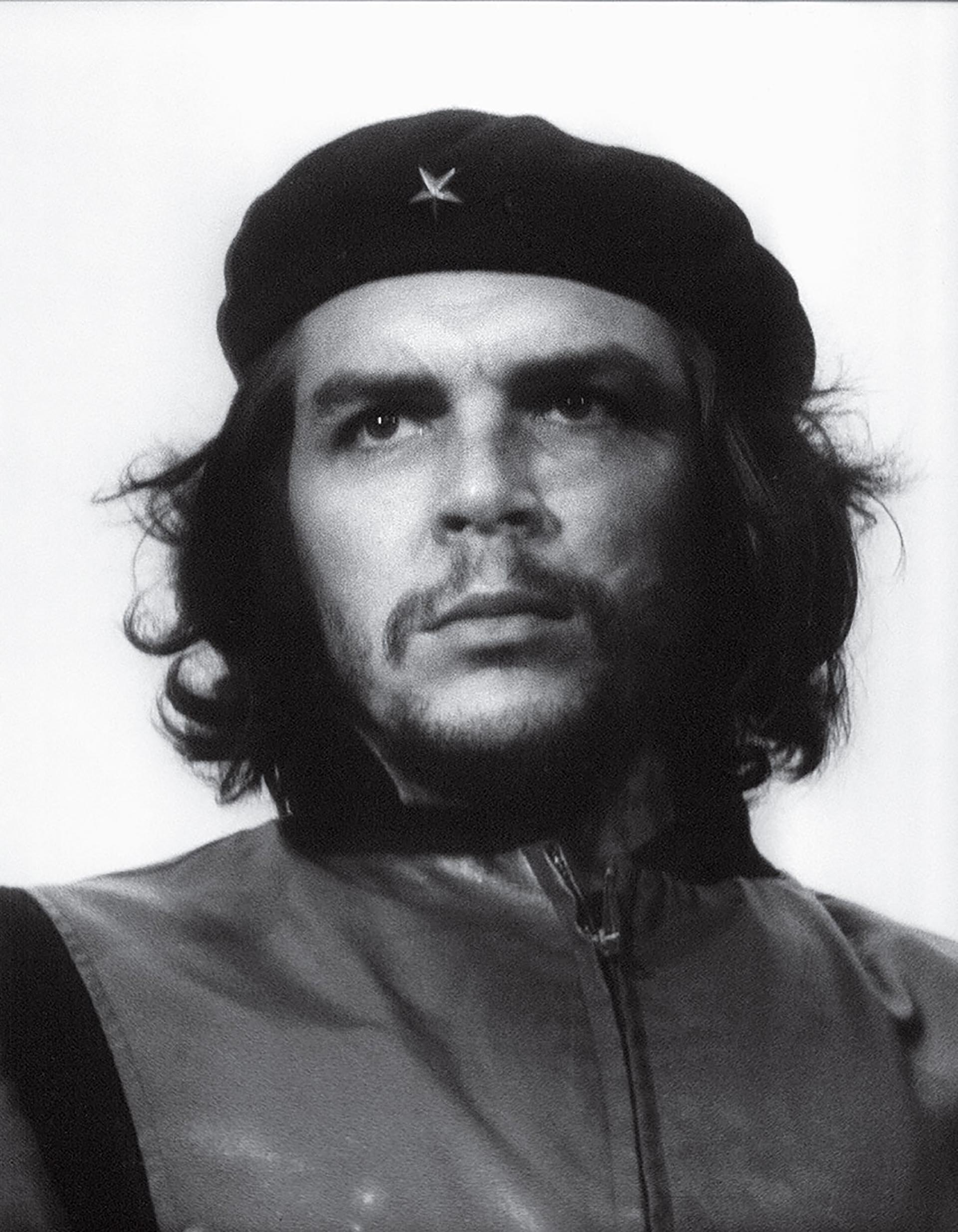

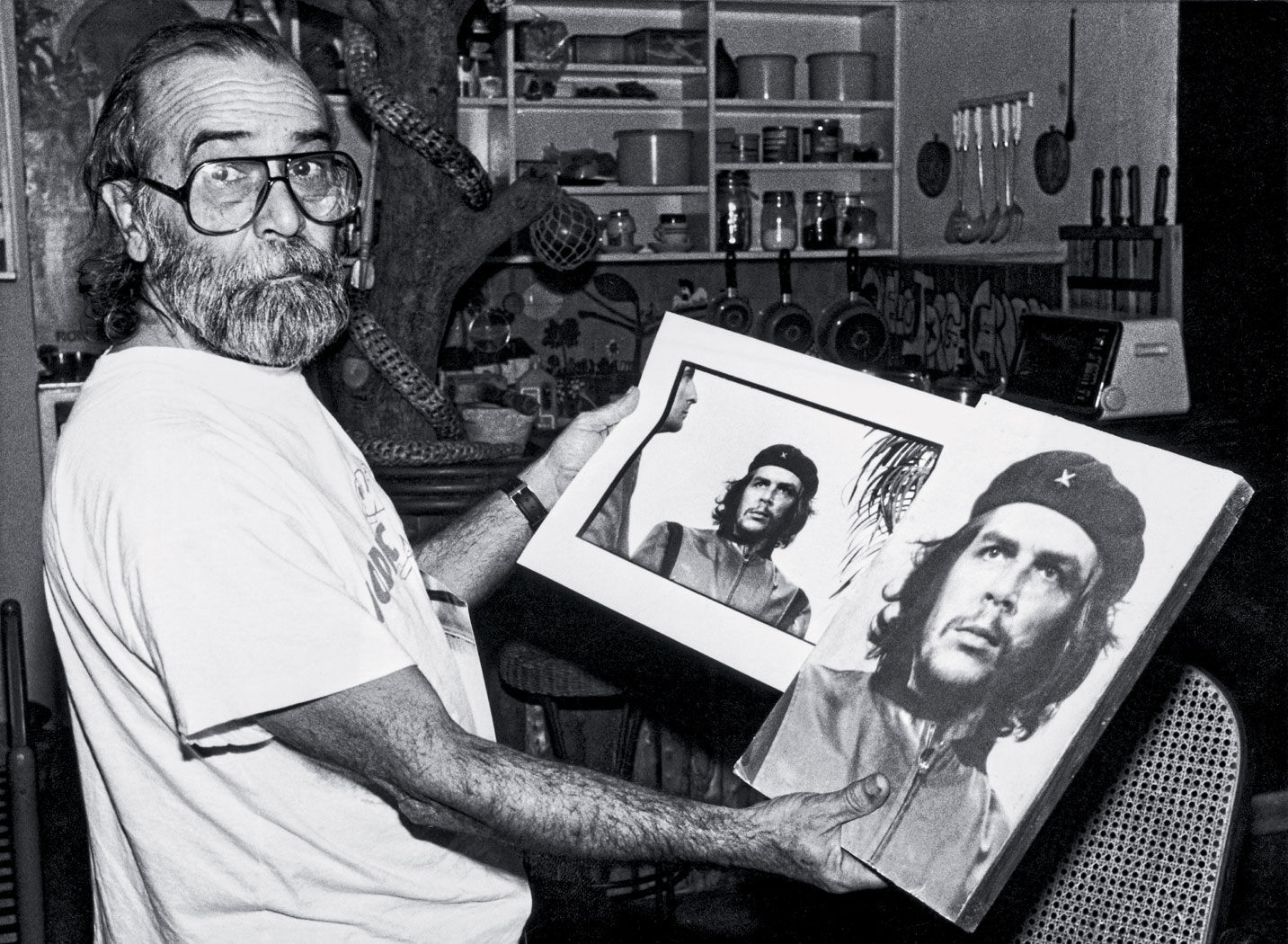

The ‘Guerrillero Heroico’ image of Che that we are most familiar with, adorning the shirts of millions, the bedroom walls of many, and imitated profusely, is one of the most iconic images of the 20th Century, recognisable by all.

But not many people know the full story behind its photographic origins, and the potential reasons why the image has compelled us so much.

On March 4th 1960, La Coubre, a 4,310-ton French vessel, was unloading her cargo of 76 tons of Belgian munitions she had transported from Antwerp to Havana, Cuba when she exploded at 3:10pm. Thirty minutes after the first explosion, while hundreds of people were involved in a rescue operation organised by the Cuban military, a second, more powerful explosion resulted in additional fatalities and injuries.

At the time of the explosion, Che Guevara (who was a trained doctor) was in a meeting at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform headquarters. He drove to the scene and spent the next few hours giving medical attention to the crew members, armed forces personnel, and dock workers who had been injured. The death toll was between 75 and 100; more than 200 people injured.

Fidel Castro immediately placed blame on the United States for the explosions as an act of sabotage.

The following day at a funeral service for those killed in the explosion, photographer Alberto Korda was there working for the newspaper Revolución. As Castro spoke, Korda got close to the platform, where he noticed that Che — who had been standing in the back of the stage — had moved forward.

“I remember it as if it were today… seeing him [Che] framed in the viewfinder, with that expression. I am still startled by the impact… it shakes me so powerfully.” Korda says.

He was struck by Guevara’s expression which he says showed, “absolute implacability,” as well as pain and anger. He managed to take just two frames – one vertical and one horizontal – before Che stepped away.

Che was furious with the United States, and Western culture as a whole, for what had happened. Che saw the United States as greedy, and selfish, money hungry, and willing to oppress and exploit anyone anywhere to feed its capitalistic hungers. The bottom line, as far as Che was concerned, was that the United States and its allies were the great enemies of justice & equality, and the core reasons why poverty and sickness were ubiquitous all across Central and South America.

Korda had managed to capture all of this raw emotion, everything that Che felt, bubbling underneath the surface of his skin.

And with it, a cultural icon was born.

Che Guevara 1928-1967

Joe Weaver, is Secretary of the YCL’s East of England Branch