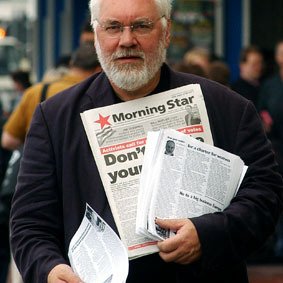

Nick Wright discusses the prevalence of rampant individualism among Britain’s media and ruling class during the coronavirus pandemic and the ideological significance of attacks on public health measures as ‘Stasi hell’. This article first appeared on 21 Century Manifesto.

How did socialist Germany’s Ministry of State Security replace the Gestapo as the bogeyman to frighten liberals out of their skins? And why is it that the confected reputation of an organisation set up by anti-nazi activists and International Brigade veterans to defend socialism and working class power is mobilised to frighten socialists out of their politics?

Since the dissolution of socialist Germany brand management has turned the ‘Stasi’ into a media trope for lazy journalists whenever the hyper-individualism of contemporary capitalism meets resistance.

Anti-socialist scaremongering has a long history in Britain. In the 1930s the first Labour government was toppled when the Tories, the Daily Mail and the secret intelligence services conspired with anti-Soviet dissidents to fake a letter purporting to come from the Communist International to Britain’s communists. Although Labour’s vote went up in the following election this was enough to scare Liberal voters into voting Tory.

And faced with the prospect of a Labour victory in 1945 Winston Churchill took to the Daily Express to foresee a ‘Gestapo in Britain if Socialists win’. Ironically, this front page headline sat alongside a photo of the Red Army staging a victory parade through the ruined streets of Berlin. And drew a telling rebuke from Labour leader Clement Attlee: “For years every attempt to remedy crying evils was blocked by the same plea of freedom for the individual. It was in fact freedom for the rich and slavery for the poor.”

But today, the Nazi’s Geheim Staats Polizei (Gestapo) are old hat. For liberals and neoliberals alike the latest incarnation of dictatorial state power is East Germany and it’s Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, (Ministry for State Security or MfS) has become the simulacrum of the social distancing rules the government proposes to limit the spread of the coronavirus. This noxious narrative is freighted with disturbing images of a surveillance state drawn from three decades of demonisation in which the German Democratic Republic has replaced Nazi Germany as the 20th century exemplar of the repressive state.

This Monday the BBC Radio 4 Today programme described the coronavirus social mixing rules as ‘Stasi-style.’

The Sun reported claims that the Government’s plans for Covid-19 marshals was unleashing a “Stasi” style clampdown on Britain’s streets.

“…socialising in groups of six is unenforcible except in a Stasi-style surveillance state” claims retired beak Lord Sumption in the Times this week. The Noble and learned Lord whose most distinctive contribution to public debate hitherto was his assertion that ‘no convincing arguments for an equal society have ever been advanced’ and that ‘no such society has ever been successfully created’ has become the BBC’s go to authority on lockdown rules.

Meanwhile a panic stricken Anne Widdicombe took to the Daily Express to give voice to worries that the police have set up a Stasi-style hotline for people to snitch on their neighbours.

Even Boris Johnson is tarred with the Stasi brush. The Daily Star has it that a ‘Stay Home Stasi’ have cancelled summer with daft Spain quarantine and it reports that ‘Boris Johnson and his confused crew changed the rules on foreign travel overnight, lumbering thousands of hard-working Brits with an enforced quarantine when they get back from holiday’.

It is not difficult to dissect the ways in which the odd alliance of right wing libertarians, anti-vaxxers, ageing hippies, oddball fascists, turncoat trotskyites and US-style conspiracy theorists find common ground in opposing eminently sensible, if limited, measures to protect society as a whole and the vulnerable from rising infections.

Each of these tendencies find common ground in a hyper-individualism in which common sense, science and good government are opposed to the over-riding imperative to ‘free’ the individual from social obligation where this conflicts with individual desires.

It is not difficult either to see how significant elements within later-day Conservatism find a synergy between their devotion to notions of the free market and the obligations that living in a modern and interdependent world impose on both the citizen and the state. It is but a short step from this narcissistic love affair with the self to a denial that our aggregate actions are risking the survival of the planet.

One expression of the capitalist cult of the individual is the idea that saving the planet is an individual responsibility. That this as the critical element in saving us from extinction is in direct contradiction to the idea that meaningful action on climate change is a matter of state policy and international agreement.

Combatting climate change and victory over the virus depends on the deployment of political and state power and in whose interest this is exercised is moot. Both the climate emergency and the coronavirus pandemic have placed collective solutions to these problems at the centre of a deep ideological divide.

The ideological effect of the ‘Stasi’ trope is performed by framing the measures an actually existing socialist state took to defend itself as a ‘dictatorship’ but one divorced from the actual circumstances in which Germany found itself after the debacle of defeat.

Wherever the US and British armies met the Red Army came to mark the post-war boundary between capitalism and socialism.

A refreshing feature of the German Democratic Republic was its frank acknowledgement that its system of political power and its socialist economy needed active measures to ensure its security.

Uniquely the socialist GDR harboured within its borders what became a highly subsidised mini state – West Berlin – where capitalist relations of production still prevailed and where a high proportion of the the CIA’s 30,000 agents deployed in Western Europe were stationed alongside substantial contingents from every other Western spy and subversion outfit.

In a state born in the ruins of nazism, with a weak and devastated economy and a population shattered by military defeat the anti-fascist veterans propelled into office faced daunting problems.

Many of the professional and managerial strata – inevitably those with the greatest complicity in the dozen years of the Thousand Year Reich – fled westwards far in advance of the Red Army.

The new state had to rely on the shattered remains of Germany’s working class movement and on inculcating a new socialist consciousness in a population emerging from decades of trauma and 12 years of Nazism whilst building a collectivist economy in the least industrially developed part of Germany.

It was a time of increasing tensions. Nazi Germany’s intelligence organisation in Eastern Europe anticipated the Nazi defeat by reaching an agreement with US military intelligence and continued under its existing head, Wehrmacht major general Richard Gehlen until 1956 when its became what is today’s Bundesnachrichtendienst still under Gehlen’s command.

Internal security in post war capitalist Germany was, and is today, down to the Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV) or Office for the Protection of the Constitution. One of its formal responsibilities is protecting the system of ‘free enterprise’. Its other duties included maintaining the system of ‘berufsverbote’ or jobs ban on left-wingers. It was the body that provided the ‘evidence ‘ for the 1956 banning of the Communist Party of Germany in the West. It was exposed as employing many former Gestapo officials when it chief Otto John defected to the GDR.

Along with the military intelligence Militärischer Abschirmdienst; MAD) these security organisations employ over 10,000 staff and an unknown number of informers.

East Germany’s state security organisation had rather different antecedents. Its first head was Wilhelm Zaissner, a former military commander in the International Brigade, its second former seamen’s’ union leader and MP Ernest Wollweber who ran the clandestine anti-Nazi sabotage organisation and supplied arms to the Spanish Republic before being captured by Swedish police and imprisoned. Its final and longest-serving head was Erich Mielke, a veteran member of the pre-war Communist Party defence unit who, upon the dissolution of the GDR, was tried for the murder of two police officers killed in the 1931 street fighting with the Berlin police.

The head of the GDR foreign intelligence organisation the Main Directorate for Reconnaissance (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung) was headed first by Anton Ackerman who had been head of the International Brigade political school and later by the legendary Markus Wolf, probably the most successful spy chief ever. When he retired he was replaced by former bricklayer Werner Grossman.

Know colloquially as der lange Arm (the long arm), die Firma (the firm) and to its staff sometimes as der Konsum (the Co-op) the MfS is regarded as one of the most effective intelligence organisations ever to have existed.

It needed to be.

Of course state security in the GDR didn’t depend exclusively on the MfS. Apart from conventional police and military formations the factory-based Kampfgruppen der Arbeiterklasse, (Combat Groups of the Working Class) had over 200,000 members.

This raises the interesting question of which capitalist state would rely for its security on armed groups of workers?

The point of this discussion is not to defend or condemn any particular policy, act or practice of the first anti-fascist state on German soil. That question was settled when the MfS – who knew better than anyone else the temper of the times – acknowledged by its actions that the three decades of German socialism was ending.

Rather, it is to demonstrate that any attempt to construct the socialist order has to contend with very powerful forces and that it is not possible without winning and maintaining the active participation of millions of people and transforming rampant individualism into a system of collective values.

Building socialism is one thing but it depends critically on being able to overcome the power of the capitalist class. In the GDR this came about when the bourgeoisie was irredeemably compromised by its support for Nazi rule and the Red Army was on hand to ensure its exit from political power.

Which again raises another series of questions. How is it that almost every challenge to capitalism that threatens a transition to socialism is met with ferocity and violence while almost every transition from socialism to capitalism has been relatively free of violence?

Given our experiences of the last three years what might this mean for a serious attempt at winning a socialist government in Britain? And when we win it how will we defend it?

End note. How effective was socialist Germany in changing opinions? At the point at which the thirty year existence of the GDR came to an end US polling organisation Pew revealed that around a quarter of those living in former West Germany (27%) expressed an unfavourable view toward Jews – about twice the share expressing that view in the former East (12%).

How effective is capitalist Germany at changing opinions. According to a new study from the World Jewish Congress 27 per cent of Germans today agree with a range of anti-Semitic statements and stereotypes about Jewish people.

One step forward, two steps back.

Nick Wright