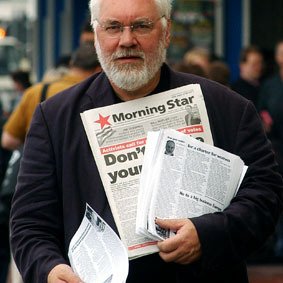

If we are serious about fighting racism we must engage with people, not get them sacked – it does not do, in a society in which the balance of power rests overwhelmingly with the employer, to become dependent on the class power of the boss, argues Nick Wright. This article first appeared in the Morning Star.

The runaway success of the Black Lives Matter movement has shaken up politics and thrown up new — and not so new — practical and theoretical problems.

Inspired by a tragic event across the ocean, a whole new group of people has found that taking the knee for eight minutes and 46 seconds — the time it took for the life to be squeezed out of George Floyd by a Minnesota cop — is the catalyst for a whole new way of thinking about racism and politics in general.

For some people to adopt a posture like taking a knee — one now so deeply embedded in US sporting and political culture — seems to strike a false note in the specifically British context.

And some right-wing politicians and pundits hide behind this excuse to cloak their unease at this new movement.

But this is the way politics works today. What happens a continent or an ocean away seems so relevant here because it serves as a reminder that these things happen here also.

Symbolic acts have a powerful effect. Last weekend the parade through Brixton of black activists wearing bullet-proof vests — nothing could more powerfully make the point that young black men are in a specially vulnerable category — has stirred up the entirely predictable chorus of outrage.

There are calls from the right wing—— a category of politicians usually unconscious of irony — for the people on parade to prosecuted for wearing a political uniform as banned under legislation passed in the late ’30s.

This law, the Public Order Act, was supposedly to rid the streets of Oswald Mosley’s uniformed fascist thugs.

It is worth remembering that it was precisely at the insistence of the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police that thousands of police were marshalled to force a way through the East End to facilitate the uniformed fascists in their aim to intimidate and terrorise.

A quarter of a million East Enders, communists, socialists, Jews and Irish dockers and their families, put a stop to that.

Uniformed fascists never again attempted to march through the East End, while in many parts the uniformed servants of the state still enjoy little respect.

For today’s Met to arrest black activists for calling attention to police violence might serve to demonstrate the political function of that force rather too forcibly for a government already under criticism.

In my modestly sized Kentish coastal town, we have an active anti-racist committee lately sprung into being.

Our Wednesday vigils — where increasing numbers take the knee — engender mixed responses.

One young activist has taken to data collection and she reports that appreciative horns honk, salutes are given and the greater part of the responses are supportive.

But not all. And when one van driver shouted out: “White lives matter!” there was a predictable response, some of it unprintable and all of it annoyed.

Controversy developed in the group when it was suggested that, as the company logo for which this character worked was visible on the van and a mobile phone had recorded his licence number, he should be pursued via his employer with a demand for disciplinary action taken against him.

And off a whole group of people went in righteous pursuit of this miserable creature.

At the same time a lively social media discussion developed about how people were responding to the controversy stirred up by BLM coverage in the media.

Some people were so upset by the reactions of their colleagues, friends and relatives that they broke off contact and “unfriended” them on various social media platforms.

I have to say that I disagreed strongly with both these approaches.

If we are serious about fighting racism and fascism we have to change the minds of millions of people and this is not easily done if we refuse to engage and reinforce barriers to dialogue that are already embedded in much of the political culture of these islands.

If we can’t convince our family, friends and workmates, who can we convince?

It is worth bringing out an issue which was extensively debated in the ’70s and ’80s.

The argument was that the term “racism” is most usefully deployed in relation to the systemic and institutionalised discrimination against black people.

Racialism, it was argued, has more explanatory power when applied to the thoughts, speech, actions and belief systems of people.

Things have moved on and we know what we mean but it is worth hanging on to that distinction.

When anti-racists retreat into their virtuous shell it looks like they are unable, or not confident enough, to challenge the racist assumptions that underlie each manifestation of hostility to BLM.

We cannot just ignore every expression of ideas which do not fit into a comfortable framework that assumes that these phenomena will go away if we refuse to engage with them.

But worse, if every passing van driver unwise enough to utter a hostile and essentially racist slogan is sacked, disciplined or admonished for “bringing the company into disrepute” the door is open for employers — whose power is rather weakly contested under Britain’s anti-trade union laws — to use this power in other ways.

And on the part of every such disciplined van driver there will be a very powerful resistance to any contrary facts and arguments that might challenge the offending racism.

Indeed, every member of the van driver’s family, every workmate and his entire social circle will be mightily angry.

It does not do, in a society in which the balance of power rests overwhelmingly with the employer, to become dependent on the class power of the boss.

Of course, public servants, people in responsible positions with authority over others are a different case.

If a cop, a civil servant, a teacher, a council employee with power to influence people’s lives were to behave in the same way, it is important that they are challenged precisely because, in their role, they act for all of us and must be seen to discharge their duties without prejudice.

It is different for the van driver who typically has little bargaining power. He shares his experiences as a worker with others and they, and their trade union — if they have one — have a much more powerful capacity to shape his behaviour and language and influence his thinking.

That is why combatting racism at work — by workers — carries so much more weight than anything an employer may do.

Nevertheless, there is a rabid and racist current of opinion, usually crudely expressed and often illustrated by a veritable barrage of online material, some of it linked to a network of Ukip/Brexit Party and Conservative circles and some of a more insidious “identitarian” trend derived from the rancid politics of the US right wing.

One such video, ostensibly of BLM activists stopping a car on a US city street, sparked a tsunami of racist comment on one local Facebook page, with the suggestion that local crime was on an upsurge.

I innocently asked if car-jacking was a big problem in Canterbury?

The ensuing discussion illustrates some interesting features of this narrative. Canterbury is, in fact, the safest university city in Britain, and violent crime in Britain, according to official statistics, has been on a steady path downwards for decades.

According to government sources, car-jacking is such a negligible category of motor vehicle crime that it barely registers.

The importance of real-life facts in this discussion is not that the people gripped by delusions are usually prepared to acknowledge that they are wrong, but more that they become less confident in their assertions, others note this and some of the toxicity is dissolved. It is about changing the nature of the discussion.

In this situation distinctions quite quickly arise between several groups of people.

One whose basic position was summed up by one correspondent: “I am rank Labour, left wing except on the EU, immigration and all this ‘woke’ nonsense,” others by people whose influences are either far-right “empire loyalist” types or stuff of a more clearly transatlantic origin — Trumpian on the surface and informed by semi-fascist identitarian tendencies.

The way this issue is often presented you would think that the problem is the racist attitudes of workers and the solution is enlightened leadership by employers.

But the reality is that the labour market is deeply disfigured by systemic racism.

Just this spring research by the University of Manchester’s Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE) and the Runnymede Trust found that systemic and persistent racial inequalities in employment, health, housing and education continue to blight the lives of black people in Britain. And worse, this puts them at greater risk from the effects of the Covid-19 crisis.

The bare facts are that apart from the well-known effects of racism in health, education, the criminal justice system and the operation of the immigration policies, Bangladeshi, black and Pakistani groups are paid less or, as the report puts it, they pay a “sustained ethnic penalty in earnings.”

Employers are getting increasingly keen to deploy off-the-shelf racism awareness programmes to head off criticism that their enterprises might be institutionally racist, discriminatory and insensitive to the needs and legitimate concerns of ethnic minority people they employ.

And a whole industry has developed which caters for this widening market segment.

This is not a new phenomenon but the intense controversy thrown up by the unprecedented public opposition to racism has provided an opportunity for the revival, in new clothing, of discredited and largely abandoned ideas.

Practically, and for an engaged working-class movement against racism, such ideas have little currency but for a certain slice of middle-class liberal opinion they appeal.

One problem for the left is that much of this stuff is dressed up in quasi-Marxist terminology and borrows uncritically from all kinds of once-fashionable intellectual trends in cultural studies, offshoots from feminism and political ideas that departed some time ago from the working-class movement and reality.

Asserting the primacy of material reality, the real-life effects of racial discrimination in the deeply embedded aspects of exploitation that characterise the world of work and life for millions of black people — in short, the reality of present-day capitalism — is deemed to be significantly less a priority than addressing the inner torments of white people confronting the “fragilities” that an increasing awareness of their privileges entails.

The utility of this approach to businesspeople worried about their exposure to litigation or the effect on their market share of a more intense scrutiny of their business practices is obvious.

Its practical effect in rooting out racism at work, in education, in health, in housing and in encounters with the police and the criminal justice system seems less obvious.

Nick Wright