Gabber is a hardcore dance music genre that fuses heavily distorted 909 kick drums with synths such as the ‘hoover’ sound on the Roland Alpha Juno, samples from the likes of old Horror movies and ranges in BPM from 150BPM to well over the 200BPM threshold.

There has been an age-old debate over the origins of where hardcore dance music emerged, with some pinpointing cities such as Detroit, Frankfurt, and Antwerp – however it is safe to say that Gabber’s entry-point was Rotterdam. The Dutch city became infamous for its club Parkzicht, where producers such as DJ Rob experimented in distorting and speeding up the sounds of House music. Rotterdam also became renowned for the label Rotterdam Records, which was founded by DJ Paul Elstak in 1992.

Although Gabber has influences from older genres such as House, New Beat, EBM, Techno and Industrial, the visual style of the Gabbers in the ’90s were generally more comparable to the British Skinheads and football hooligans than the neon-clothed Acid House ravers, with bald heads being one of the most distinguishable trends of the subculture. In addition to the Skinhead hairstyle, most Gabbers wore colourful tracksuits from brands such as Australian L’alpina, and also commonly wore Nike Air Max trainers.

The raw anger and darkness of many of the tracks were a long shot from the loved-up generation of Happy Hardcore ravers. Over the last few years, there has been a recent global resurgence in the popularity of Gabber, in part due to the revival of Gabber’s most notable events company Thunderdome, but also with the revisiting of the style by fashion brands and deconstruction of the sounds by so-called post-Gabber/neo-Rave music producers.

Gabber in the 1990s in particular was undeniably a working-class youth subculture. Booming in industrial European cities such as Rotterdam, Hamburg, Glasgow, and even cross-continent in the former steelworks-dominated city of Newcastle, Australia, where the record label Bloody Fist emerged, Gabber attracted with it an army of bald-headed mainstream-disenfranchised youth, many of whose parents worked in industrial sectors.

From the start, Gabber was heavily tied to football hooligan culture, with a large following of the Dutch football teams Feyenoord and Ajax in particular. Many Gabbers and DJs themselves sported football tees at events and within Dutch football stadiums to this day, it is not uncommon to hear the genre being played out of the stadium speakers. Although some interpreted the hooliganism on the face as baring signs of far-right nationalism and xenophobia, on the most part, hooliganism represented to Gabbers an ethos for living a drug-fuelled hedonistic life of chaos and as a means of forging a fraternal sense of community amongst one another. Within the world of football itself, hooligans span amongst many political ideologies, not just amongst fascism.

In Britain, although having been played at various megaraves such as Fantazia and even appearing on Top of the Pops at one point (Technohead), Gabber reached British newspapers in 1997 due to the Daily Star’s journalist Lee Harpin creating a sensationalist article titled ‘Nazi Gabber Hell’. Within the article, Harpin wrote that “Nazis have adopted Gabber music as their unofficial anthem” and that the “sickening scene is taking hold of Britain.” Concluding the article with “parents, you have been warned”, what this journalist had intended was to fearmonger and fabricate an ethical hostility towards the music genre itself as opposed to a few individuals within the scene. This whole article was completely misinformed and Harpin even wrote a whole paragraph on the veteran London DJ Loftgroover, lumping him in with Nazism, without even realising that the artist he was writing about was black. This article angered a large part of the scene including Loftgroover himself who responded by saying “If you go to a speedcore thing, 99 percent of the people are white, and, to establish themselves as a bit different from other ravers, they shave their heads. So you’ve got a load of white boys and girls with shaved heads, all sweating, and suddenly everyone thinks ‘Nazi!’.”

Although the scene back in the ’90s was predominantly white, some of the biggest artists in the scene such as Darkraver and Rotterdam Terror Corps’ MC Raw were black; even Carl Cox for a brief period produced Gabber under his former record label MMR Productions. Moreover, the media’s desire to scandalise what was then at least a predominantly working-class subculture, emphasised the classist hatred much of the media felt towards hooliganism and anything remotely Skinhead-related.

This attempt to tarnish the whole Gabber scene echoed back to the British media’s villainisation of Skinheads as being violently thuggish fascists, when for a matter of fact many ethnicities attended Oi! nights, especially as the music had multicultural influences with Ska, Dancehall and other forms of Reggae being the dominant ones. Furthermore, the presence of S.H.A.R.P. (Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice) amongst the Oi! Scene and music from Marxist Oi! bands termed ‘Redskins’ proved how many had resisted being lumped in by the media with the fash.

The word Gabber means ‘friend’ in Dutch and was first coined by DJ K.C. the Funkaholic in an interview where he described the scene as a “bunch of gabbers having fun.” However the etymology of the Dutch word itself stems from Holland’s Jewish history, originating from the Yiddish word ‘chaver’ which can also mean ‘comrade’. Alongside the Jewish origins of the name, the Amsterdam-based label Mokum who were notably responsible for releasing the biggest selling record in Gabber history: English duo Technohead’s ‘I Wanna Be a Hippy’, take their name from the Yiddish word for the central borough of Amsterdam which translates into English as ‘safe haven’. Holland has a longstanding Jewish history, especially in the former merchant port of Amsterdam, where many Jews fled persecution from countries such as Germany and Spain from the 12th Century onwards. Consciously embracing their regional Jewish history, the Mokum artists Party Animals have even released a song ‘Hava Naquila’, adapting a traditional Hebrew folk song into an over-the-top happy and cheesy hardcore track. Hava Naquila is a popular football anthem for the fans of Amsterdam’s Ajax and is even occasionally chanted by Tottenham Hotspur in the UK as a means of celebrating their team’s Jewish origins.

In a similar vein to the antisemitism often chanted by other football teams towards Tottenham here, Ajax has historically had the same abuse hurled at them by some far-right fans of other national teams, especially some of the fans of Rotterdam’s Feyenoord were known for some instances of gesturing ‘seig heil’ salutes and making hissing sounds to imitate the gas chambers. By the late 1990s, many of the Jewish Ajax fans avoided going to play-offs in fear of receiving abuse or even physical assault. The far-right extremism within football stadiums equally encouraged Mokum to adopt an anti-racist stance just as much as what was happening within the Gabber scene itself. On the other hand, it also cannot be denied that Ajax has its own issues with right-wing thought amongst some of its supporters, most notably that of Zionism. As well as the inescapable presence of Israeli flags at Ajax matches, there has also been a history of confrontations with pro-Palestine fans of teams such as Celtic.

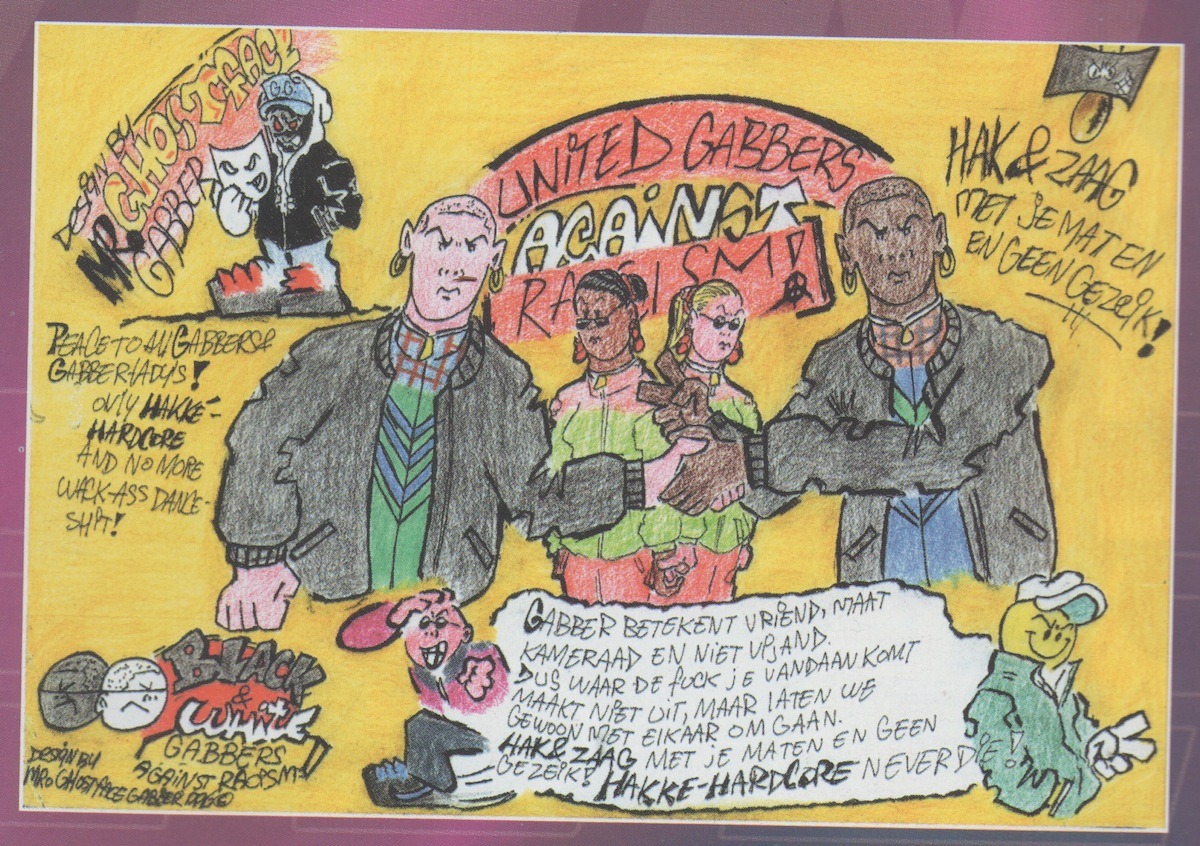

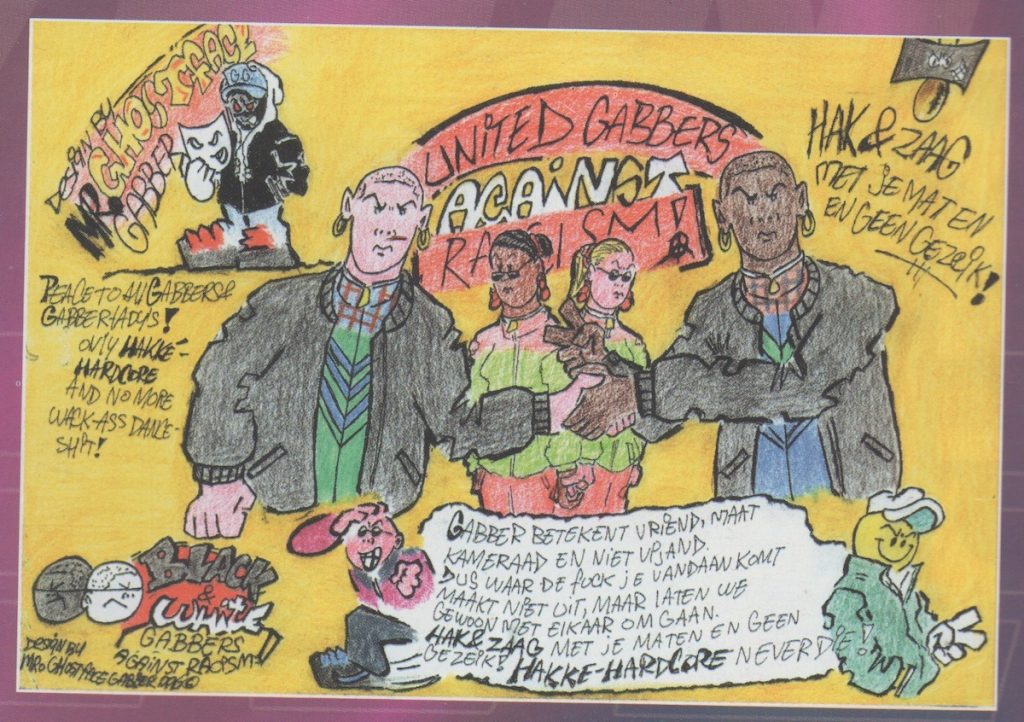

In addition to embracing Dutch-Jewish history, Mokum are undeniably antifascist and and have released songs such as Chosen Few’s ‘Chosen Anthem (Against Racism)’ and Party Animal’s ‘Die Nazi Scum’ featuring American producer Rob Gee. In addition, each physical vinyl release had a printed sign that read ‘United Gabbers Against Racism and Fascism.’ The sign was arguably inspired by the S.H.A.R.P. movement amongst anti-racist Skinheads from 1986 onwards. Mokum’s contribution was one of the most longstanding and symbolic signs of anti-fascism within the Gabber scene and still until this day, Mokum brandishes their anti-fascist and anti-racist sign upon their releases. It must be noted that Mokum were not the only label during the mid-to-late 1990s advocating anti-fascism, with labels such as Hamburg’s Nordcore Records using the image of a bulldog destroying a swastika on their posters and flyers. Also, alike to Mokum’s closeness to Ajax, Nordcore were strong supporters of Hamburg’s St. Pauli and even released the song ‘St Pauli Hymn’ as a means of honouring the team and their infamously socialist Ultras. One artist in particular has even gone as far as making antifascism his very name: the German producer ANC a.k.a. Anti Nazi Core who started producing Gabber and its faster subgenre Speedcore from 1993 onwards.

The fascists amongst the Gabber scene in the 2000s became known in the media as the Lonsdalejongeren a.k.a. Lonsdale Youth. The ‘Lonsdale Youth’ look consisted of Lonsdale shirts, rolled up jeans and Doc Martens, appearing more traditional Skinhead than the former sportswear-driven image of the Gabbers prior in the ’90s. However, not only did the media coin the term, but in many ways fabricated much of the situation by lumping people wearing the same attire as supporting the same ideology and as statistics show from Holland’s national security service the AIVD, only 5 percent of youths amongst the scene wearing Lonsdale held fascist beliefs.

The first fascist organisation that was trying to take advantage of the hysteria around the so-called Lonsdale Crisis was Stormfront Netherlands (SFN). Stormfront Netherlands were founded in 2000 and as their name shows, were undeniably neo-Nazis. Stormfront tried to recruit supporters amongst Gabbers by right-wing extremist propaganda and the organisation unlike older fascist and right-wing nationalist organisations proclaimed that they were tolerant of drug usage as a means of recruiting more partygoers. However, Stormfront still had a marginal involvement within the scene, with an average of 50 to 100 Gabbers involved in their demonstrations and meetings at a time, even with the occasional leafleting at Gabber events such as the Rotterdam Dance Parade. During their existence immigrants received verbal and physical abuse including fatal stabbings and a Jewish cemetery was even vandalised.

After Stormfront Netherland’s collapse in 2002, it appeared on the surface that the fascist problem had momentarily vanished. Fascists have traditionally targeted youth groups as a means of mobilising them into direct action. Football hooligans and Skinheads had traditionally been targeted by such organisations, most notably in Britain with the National Front and British Movement from the late ’60s onwards. By aggressively targeting a youth movement, fascists had the potential to galvanise a larger membership base. Seizing on successes of other organisations albeit marginal ones, the British fascist organisation Blood and Honour established a branch in the Netherlands. The significance of Blood and Honour was their involvement in British Skinhead culture from the ’80s onwards, helping organise the Rock Against Communism events. Blood and Honour was also directly linked with the British neo-Nazi terrorist group Combat 18 who were renowned for their anti-communist doxxing magazine Redwatch which later became the website under the same name.

During this period, there were also occasions where fascist Gabbers who ran Gabber fan webpages sported celtic crosses, images of Adolf Hitler and iconography of various European far-right and fascist movements such as the now defunct website Holland Hardcore. Additionally, obscure fascist Gabber ‘artists’ started appearing online, creating names such as Aryan Techno, Dj Adolf and Panzerfaust, songs with reactionary titles such as ‘Gabber United Against Antifa’ and even edits of known gabber songs such as the contradictory blend of music by the multi-racial group Rotterdam Terror Corps with samples of Hitler speeches. Contrastingly and arguably more prolific on Gabber websites however were signs that said ‘United Hardcore Against Racism and Fascism’ etc. Many Gabbers tried their hardest to wipe fascism off the face of the scene and fights between the antifascists and fascists were not unheard of.

As a response to elements of fascism within the scene and the Dutch media’s infatuation with the so-called Lonsdalejongeren, events and festival companies such as Masters of Hardcore used anti-racist signs on their flyers. Additionally, in Eindhoven during June of 2005 several hardcore promoters banded together to put on an event titled ‘United Hardcore Against Racism’. Many of the big names in Gabber either performed or attended and the festival itself gave a clear view on the role of racism and fascism within the scene. All of the proceeds from this festival went towards Holland’s National Bureau for Combatting Racial Discrimination (LBR) and not only attempted to ward off the fascists and far-right from the scene, but moreover helped convince the often over-sensationalist media that Gabber is not inherently neo-Nazi. For the festival, a record called ‘Time To Make a Stand’ was also released by the likes of Angerfist and Neophyte as a means of creating an anthem for the antiracist festival.

Another event with a clear antiracist and antifascist ethos is Berlin’s annual street parade, the Fuckparade: aptly named after the Loveparade, but unlike the latter, challenges commercialism, far-right politics and offers some of the most abrasively extreme and fast-paced hardcore dance music there is. Equally, the Fuckparade’s flyers garner anti-fascist signs and past parades have seen demonstrations within it against far-right movements such as Pegida and Germany’s AfD (Alternative for Deutschland) Party. German rave music in particular has a history of Communist influences. Be it Breakcore artists such as Karl Marx Stadt, Classless Kulla, Istari Lasterfahrer and labels such as Socialitzcher Plattenbau, Praxis or even the Acid Techno label Communism Records, there is undeniably a sense of nostalgia for the former GDR and a desire to break away from the clutches of neoliberalism and American imperialism.

Fascism is still an issue within hardcore dance music, but is no way near as widespread as it was when there was a direct linkage between Gabbers and organisations such as Stormfront. Although there have been photographs of topless individuals with swastika and ‘white power’ tattoos at festivals such as Dominator posted online, the fringe minority of fascists in the scene do not appear as organised as they were during the early 2000s. However, individuals are still keen to revive the antifascist politics of Gabber for this day and age such as the Italian-born producer and archivist Gabber Eleganza and his label Never Sleep Records. Despite appearing more highbrow than hooligan, his new 2020 compilation album URAF (United Ravers Against Fascism) attempts to rekindle the antifascist stance previously adopted within the scene. Alarmingly however, the compilation includes only one Gabber artist (albeit the old-school legends Ilsa Gold), the compilation mainly consists of experimental techno tracks and so-called ‘post-Gabber’. Gabber purism aside, proceeds of the compilation went towards Ivorian-Italian trade unionist Aboubakar Soumahoro’s fundraiser for black migrant workers in Southern Italy, the Auschwitz Memorial and Seebrücke; a German charity fighting for the rights of refugees crossing the Mediterranean.

Although Gabber’s heyday is done and dusted, the style has mushroomed into many types of hardcore genres, with each one bringing along with it like minded individuals with anti-racist and antifascist sentiment who will always be there to take a stand against the fascists. As far-right politics keep intensifying globally and as the working class are routinely branded by the mainstream media as illiterate, xenophobic thugs, the working class youth today needs to band together as comrades, whether through a youth organisation or even on a night out.

Tomasz Nowak