Joe Rosenthal discusses the history of Communist Party involvement in organising rent strikes and what lessons can be learned and applied in today’s struggles.

The market is said to control the price of rent. However, landlords own large chunks of property and will often withhold property in order to artificially inflate the market prices of rented accommodation.

The cost of rent is forecast to rise by 15% in Britain over the next five years and real wages are stagnating. Whilst this is the result of capitalism’s inherent contradictions, there are many ways in which people have fought and continue to fight to effect real change whilst we progress towards revolution. One of the strongest tactics people have employed against unfair rent, is through rent strikes.

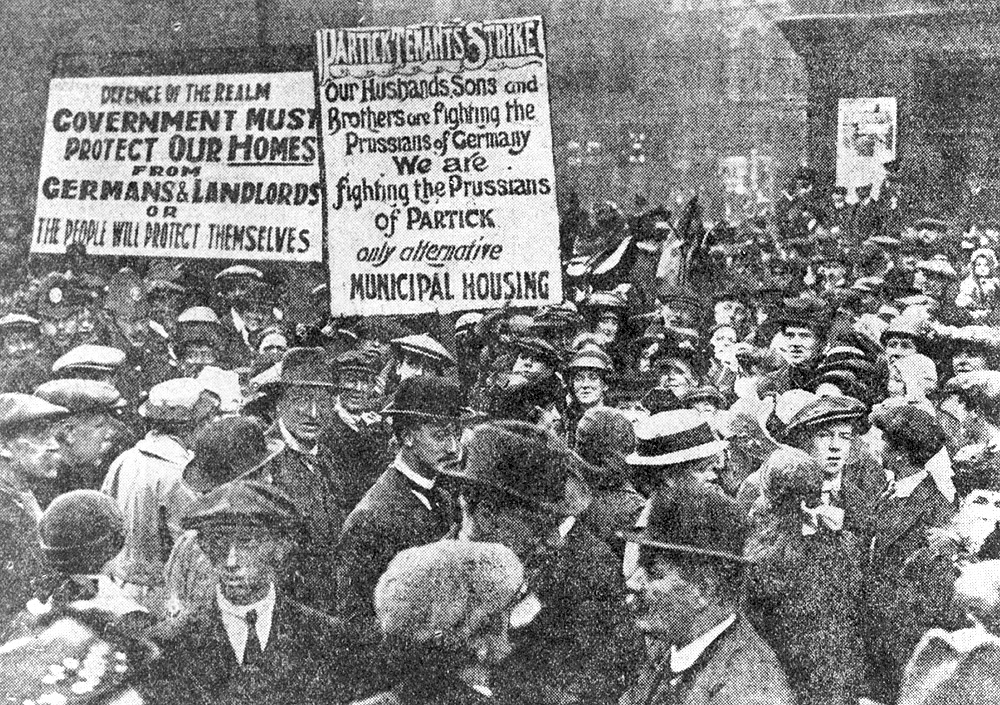

The Communist Party played an integral part in the rent strikes. One popular tactic was for party members to go around all the houses in a street and ask the tenants to pay only the regular amount of rent, not the extra that had just been hiked up.

Women played a particularly prominent role in the rent strikes. The women of the Communist Party were lynchpins who helped organise resistance to landlords. Another popular tactic was where women would switch the nameplates on the doors, in order to confuse the bailiffs who were unfamiliar with the area.

Sometimes these tactics were not quite enough and when someone was facing eviction, the tactic of direct action was employed. Entire streets worth of tenants would flood the street to stop the bailiffs passing.

Another form of rent strike is the use of squatting. Squatting is where people occupy an empty piece of private property that has sat dormant and is not being used to house people. The squatters do not pay any rent to the landlord whilst they are squatting there.

The Connolly Youth Movement in Ireland have had great success at implementing squatting within a communist framework. The movement have implemented communism’s rejection of private property by taking over a former house that has been allowed to become derelict through the hoarding of accommodation under capitalist notions of private property.

The stereotypical view of squats is that they are unsanitary places, but the Connolly Youth Movement have implemented cleaning rotas and principles of democratic centralism, that make for an efficient way of occupying capitalist private property.

There is a proud real socialist history of rent strikes in Britain, although this could be the subject of a whole book, we have tried to cover what we found the most relevant and intriguing.

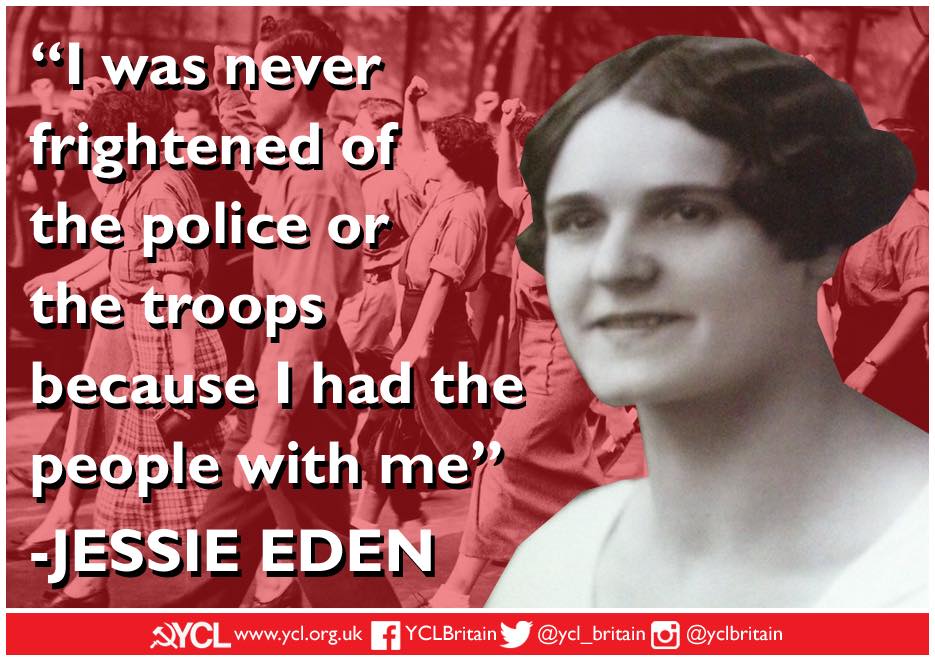

In the summer of 1939 some 45,000 council housed tenants in Birmingham stood up to Tory rent increases via a mass strike. The 30s’ in Brum was ripe with working class resistance, such as prominent trade unionist Jessie Eden leading 10,000 women out to the Joseph Lucas Motors picket line in 31’, in refusal to the new ‘Beaux’ system introduced in which pay depended on a dubiously measured level of productivity. This women’s strike amongst more industrial action defeated the Lucas bosses, heralding the headline of the 29th January 1932 Daily Worker to be ‘VICTORY! BEDAUX SYSTEM SMASHED!’.

In the advent of further successful industrial action and the slight restabilising of the economy, towards the late 30s’, small sections of Birmingham’s proletariat were receiving a few extra crumbs from the table of the bourgeois, this became an excuse for the Tory council to hugely increase rent on municipal homes, although the real reason was simply so they could lower council tax for their core voter base of middle class home owners.

The rent rises were questionably means tested, based on the size of one’s house, hitting hardest families who had bigger homes to facilitate their children. The Tories sent out forms to means test people in the communities. These did not get filled in. They attempted further coercion by offering temporarily rebated increases for lower income tenants. This did not change many perspectives.

Soon enough Birmingham’s Central Tenants Association got involved, headed by Communist party member Ted Smallbone, with previously mentioned Jesse Eden (now also in the CP) as vice secretary.

Close to when the increases were to be introduced, the CTA arranged a vote regarding a rent strike throughout Birmingham’s estates in the April of 39’. Around 92% were in favour. In a fierce battle, tenants withheld rent from the council for ten weeks. Whole communities were in a state of militancy, protecting their communities from the force of bailiffs and rent collectors. The CTAs own paper, ‘The Tenant’ was used to propagate and maintain the strike, with its circulation of 40,000, using this, signs stating ‘’No rent: On strike’’ were given to tenants and put onto thousands of windows.

The high level of organisation in the strike and the frequency of mass street protests struck fear in the hearts of Birmingham’s elite, showcasing the irrefutable power of an organised working class. The establishment paper The Birmingham Post desperately attempted to break the strike by claiming that most tenants were secretly paying their rent and merely pretended to be striking in fear of ostracization. There was little to no evidence to confirm this. The strike continued at full pace. The council was put into a corner they could not escape, and on the 3rd of July 1939, closing in on the outbreak of world war, the council caved in and abolished the rent increases, maintain the rebated rents and even ushered a promise of 50,000 new municipal homes. These huge compromises showed the power and potential of this rent strike movement, perhaps there would have been a lot of revolutionary potential had it not been just before WWII. Albeit, this brought the Communist Party to the forefront of the rent movement.

Despite the positive effect of post-war housing reform, Britain’s bourgeoisie inevitably still had the intention to squeeze as much as they could out of tenants, which was of course met with fierce resistance.

A notable event being the 1959-61 St Pancras rent strikes. Instigated because of the 1957 Rent Act, which stated that the level of rent would be based on rateable value and also because of the Tories taking control of the Borough in 59’, further increasing the rents. The United Tenants Association, comprised of 35 different labour organisations, suggested a strike, this was carried out by 8,000 tenants, all then threatened with eviction by the council.

It all kicked off on the 22nd of September 1960, when the council sent five bailiffs, accompanied by eight hundred police to evict two leaders of the strike; Arthur Rowe and Don Cook. The community was quickly alerted to what had happened and rushed out of bed to help on that climacteric early Thursday morning. Soon enough, there was a full-on battle between tenants and the police. Their batons were matched with whatever could be found; rocks, sticks, milk bottles…

There were dozens of injuries and arrests, all for the sake of working-class solidarity against the systemic exploitation imposed on them by these policies of Rachmanism. The strikes eventually came to nothing due to the brutal repression by the class traitors within the police, despite this, it reaffirmed the revolutionary potential of mass strikes and showed that there’s an alternative to the conventional politics of pleas, polls and petitions.

There were other significant rent strikes post WWII. One was the East London rent strike of 1968-70. The Tory ran Greater London Council (which was the biggest municipal housing authority in the country), proposed a policy to try and match the price of social housing to that of the private market, which would have increased rent by an average of 70% over the next three years, this resulted in thousands striking and 20,000 protesting on Trafalgar square in solidarity.

In July 1970 the GLC wrote to tenants that if they did not pay up in three weeks they would be evicted; this prompted the creation of an anti-eviction committee and further protests outside the city hall. Eventually the government were forced to step in, shook again by the fear of strong popular resistance, and forced the Greater London Council to retract the increases.

Albeit, my research began to dry up when looking for rent strikes in the 80s’ and beyond. This we have put down too many factors, particularly due to the ‘quieting down’ of real left-wing politics and the rise of Neo-Liberalism. This manifested itself with the elections of the likes of Reagan and Thatcher, the imperialistic destruction of Allende’s socialist project in Chile and the rise of reactionary nationalism in Britain, with the Falklands war and the breaking up of the Britain’s Communist party in 88’.

These are among a plethora of grim events. This period can be defined as an age of nihilism as far as the cause of building a better world is concerned. Nevertheless, to borrow from Engels, this period seems to be withering away. In Scotland, the grassroots tenant’s union, Living Rent, with many Party and YCL members involved, are building a strong network of resistance against exploitative private landlords and unifying local authority tenants who have been too long neglected by the council. This can be seen with their outreach programme in the Muirhouse estate of Edinburgh.

There is also ACORN, Living Rent’s sister union, operating in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Their work has liberated thousands of tenants from unfair evictions and unjust money grabbing from previously unchallenged landlords. Only time will tell what the future brings, but the power of British communists and therefore the working class is inevitably on its way up.

Joe Rosenthal