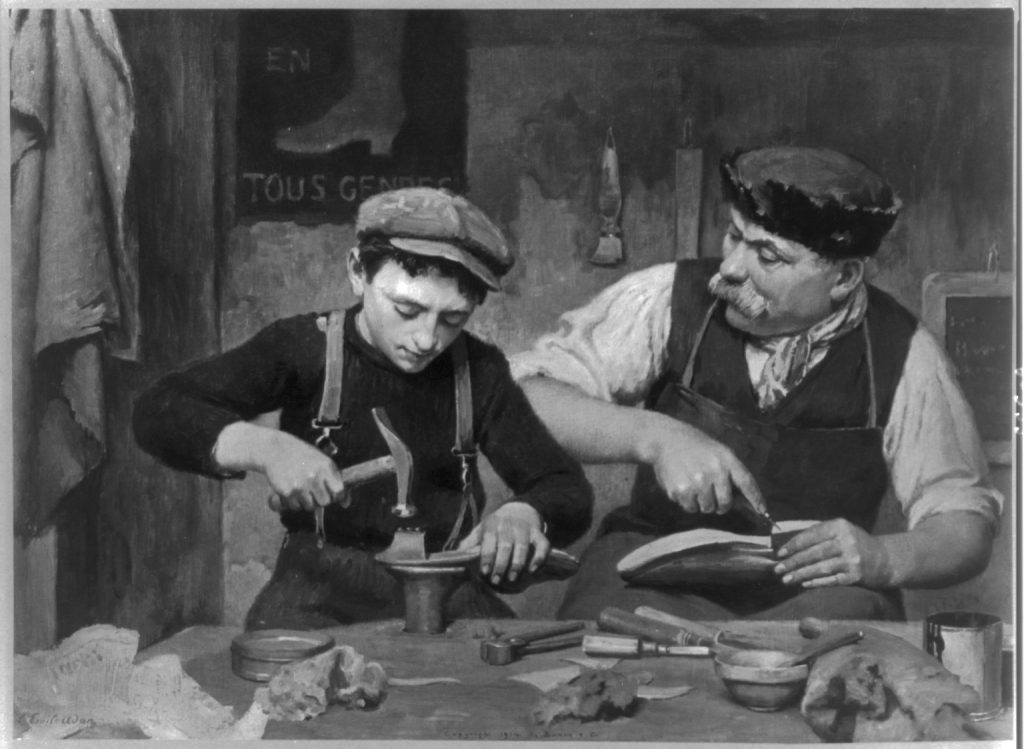

Apprenticeships, on paper, sound like a fantastic initiative, right? Learning practical skills for the workplace, gaining qualifications, all while earning a wage. Indeed, there is a romantic image surrounding apprenticeships that still pervades among popular opinion, students learning to become skilled craftsmen at the foot of an all knowing master, the making of the artisans of the future, all very nostalgic.

It was this romantic image that was harnessed by the Conservative Government in its push for apprenticeships, including degree apprenticeships, to be rolled out en masse in the early 2010s, with Cameron vowing to create 3 million apprenticeships, including prestigious ‘degree apprenticeships’, in 2014, payed for via cuts to housing benefit of course.

However, despite the romanticised image of apprenticeships, the reality is often far less rosy. Think more stacking supermarket shelves than skilled engineering work, construction or forging artisan objects. For many instead of creating opportunity, apprenticeships have instead open the gates for exploitation, with apprentices instead of learning skills, simply being used as cheap labour. Perhaps the clearest illustration of this can be see when one analyses the type of apprenticeships being offered, with a quick google search I found a ‘Hospitality Team Member level 2 Apprenticeship’ at McDonalds, a ‘Retail Level 2 Apprenticeship’ at Superdrug and a ‘Customer Service Apprenticeship’ at Boots listed as some of the courses available to young people.

It is important not to undervalue the importance of workers in sectors like Customer Service, especially in light of Covid 19. However I would argue that these apprenticeships, paying a minimum wage of £3.90 an hour with no job guaranteed at the end, do exactly that. In customer service and hospitality, it is common to learn skills on the job, rather than through an apprenticeship. By setting up such schemes, employers such as supermarkets have found an easy way to slim their payroll, and by doing so undervalue the labour of its employees. While Apprenticeships can be found in many sectors, including those traditionally associated with higher pay, the existence of the apprenticeships leading to jobs which in normal circumstances require little training suggests that companies are looking to take advantage of the scheme, and in turn enrich themselves.

I also question the value of such apprenticeships, especially considering that the Level 2 qualifications, most commonly offered, are equivalent to GCSE grades, rather than the A Level grades needed to progress onto further education. 68% of apprentices start apprenticeships at a qualification level below the ‘natural step up’. Furthermore the ‘degree apprenticeships’ advertised as the cutting edge in further education remain increasingly oversubscribed and few and far between.

Indeed, what becomes increasingly clear, especially when one considers the lower minimum wage for apprentices, is that many companies have taken advantage of the raising of the school leaving age by offering apprenticeships that benefit them, rather than the students undertaking them. This is especially concerning when we consider the attractions of such courses for students of disadvantaged or poorer backgrounds, who, in light of the spiralling costs of university, often see apprenticeships as a more affordable option for gaining qualifications. While vocational training is just as valid as further academic study, why are companies able to fail students in offering courses of low quality and value?

Research by the TUC has found that of the 900,000 apprentices in England, 135,000 weren’t even being paid the poverty £3.90 minimum apprentice wage. Freedom of Information requests have revealed that, between January 2016 and June 2017 (the most recent statistics), the government had prosecuted fewer than 5 employers for failure to pay the apprenticeship minimum wage. Most companies only pay 10% of training costs with the government subsidising the other 90%.

It is little wonder then that apprenticeship uptake has entered a period of decline. The number of starts in England was down from 509,000 in 2015/16 to 376,000 in 2017/18. Welsh figures tell a similar story, having fallen by almost 20% in November 2018 – January 2019 compared to the same period in 2017/18.

It’s fairly clear that there’s a level of class based exploitation surrounding these ‘phony’ apprenticeships in which students, often from poorer backgrounds, are getting a raw deal; but that does not mean that vocational qualifications have to be that way. A great example of decent vocational training can be found in the Industrial Training Board, offering qualifications known as ‘ITBs’, which ran from the 1960s to the 1980s when they were closed by the Tory Government of the time.

Ran in partnership by Unions and Government, students were guaranteed unionised jobs at the end, and training was generally at high standards. A far cry from many of the apprenticeships offered today. Indeed there is a clear role for vocational training within our society, but there is no need for the profiteering and exploitation that the current system encourages.

The education system in this country actively works to further class exploitation, and the problems regarding apprenticeships are yet another symptom of this. As Communists we should be calling for free high quality education for all, throughout life, including vocational training. An educated working class is an empowered working class. The call for a National Education Service in the last Labour manifesto was a good first step towards this and I for one, hope that under the current leadership, this policy will not be dropped.

It’s also good to see the work being done by unions regarding apprenticeships, with unions including Unite and Unison calling for a full living wage for apprentices and offering subsidised rates; in the coming years it would be fantastic to see growing union membership amongst apprentices in order to counter the exploitation of young workers. Union membership amongst young people is low and the YCL has a role to play in countering this through building class consciousness amongst British youth. However, simply unionising is not enough, large companies like McDonalds and their CEOs have no role to play in educating the young.

We need a new national government backed apprenticeship system focused on real skills and real jobs with dignified pay and day one trade union and employment rights. This can only really be implement and achieved in the context of public ownership of utilities and state investment to rebuild Britain’s manufacturing sector. Communists must go further and work for a world in which education is for the people and by the people.

Amy Field