This article will rightfully be dominated by the commemoration of fourteen innocent civilians who lost their lives amidst the terror inflicted by colonial troops in Derry. The incidents of January 1972 remain etched in the memory of the city and the island, serving a fatal reminder of just how far a colonial order in London will go to maintain hegemonic order over the indigenous Irish in their homes and communities.

The Irish Bloody Sunday is propped up by endless comparable accounts throughout republican history, but it is important to note that imperialists throughout the world maintain similar strategies to subjugate populations to the whims of a ruling class, even within their own domestic boundaries.

This is particularly relevant when analysing the events within Russia in January 1905; a Tsarist autocracy hell-bent on stubbing out resistance to its rule ruthlessly turned on a national Russian population collectively fighting for political and economic reform, a massacre that has also been dubbed with the infamously renowned title of Bloody Sunday.

The heavily financed defeat in the Crimea against British imperial efforts three decades before had forced the Tsarist autocracy to concede limited economic reforms to an aspiring bourgeois national class, producing a new sense (however limited) of industrialisation throughout the country. As an urban population began to hold an ever more efficient role in national economic production by the early 1890’s, class-inspired tensions began to flair amidst the appetite for political reform, with industrial action and a new sense of worker organisation an ever present threat for a Tsarist ruling-class to contend with.

A climate of rising unpopularity forced the Romanov dynasty to gamble; Nicholas II and his close array of advisors remained adamant that further imperial expansion in Manchuria at the expense of the Japanese could refuel popular sentiment for their rule, and prompt a ‘one-nation’ ethos that could inspire class reconciliation in the interests of Tsarist prosperity.

Their bungling efforts produced nothing short of a national crisis; with Russian fiscal and military endeavours so heavily focused on the war with the Japanese in mainland China, rising food shortages across national boundaries ensured an ever-increasing acceleration of popular discontent towards the Tsarist regime that threatened to permanently expose the frailties of the state. Future legitimacy of the Romanov empire seemed bound to a successful culmination of the Russo-Japanese War, with rising protests ever eager to strike a fatal blow into what Vladimir Lenin described as the ‘rotten core’ of a fortress that had once been seen as impenetrable.

Indeed, even though the Russian Social Democratic and Labour Party (RSDLP) that Lenin represented had split into two factions of Bolshevik and Menshevik amidst theoretical differences in 1903, rising membership of the party ensured that many remained hopeful that calamities at Port Harbour and beyond could determine real change for working people at home.

The pendulum swung towards revolutionary ambition in the early days of 1905, with the Japanese landing several crucial victories against Tsarist forces, most notably at the Battle of Mukden, where Russian troops had significantly outnumbered Japanese state forces and still been dealt a crushing defeat. Amidst the debacle of family members being slaughtered at the front and an ever-increasing food crisis, Russian workers voted with their feet; a wave of strikes erupted across many industrial heartlands in protest to the war, most prominently amongst those producing vital weaponry in the military factories necessary to maintain the imperial presence in Manchuria.

With Tsarist war efforts now bereft of supplies and lacking support within working-class communities across national boundaries, protest and organisation gathered momentum. Indeed, by January 8th workers had effectively stopped the spread of right-wing newspapers across the capital and sufficiently sabotaged electricity supplies to many Tsarist government and military buildings across other major cities. Tempers had reached fever pitch, and a growing awareness began to spread amongst industrial workers that the opportunity for change and further concessions from a Tsarist ruling class could be lost to the pages of history without a lasting mobilising effort on government office.

The dialectic of contradictory forces had reached the critical point of conflict upon Russia’s shores; industrial concessions made by Tsarist offices in the wake of the Crimean defeat had spawned and produced a proletarian undercurrent that now had the desire and organisation to challenge for a society built upon their own economic interests and social customs. Workers from St. Petersburg to Moscow had built the battleships and armoured weaponry that were being sunk and destroyed by the Japanese in the Tsushima Strait and beyond, and were now willing to construct their own theatre of hostilities against a Tsarist ruling class at home.

The culmination of protests and strike action became organised into a single demonstration on January 9th, mobilising thousands of workers to march upon the Winter Palace as a collective effort of objection to the conduct of Tsarist officials and Nicholas II himself. Accentuated involvement from a rural peasantry boosted already impressive numbers, but with this swelling of countryside influence came more conservative approaches; an industrial class enthused by Marxist doctrine had to contend with a rising religious influence amongst the protest that advocated a mere checking and balancing of Tsarist ruling class authority rather than expropriating it.

The growing sway of Orthodox priests and large rural numbers still influenced by Tsarist traditions in spite of the national situation ensured that the protest itself became more conciliatory than originally planned, with a petition drawn up to the ‘tsar-father’ written in trust that he would listen and grant further concessions to working people throughout Russia. For those who had brought major cities to a skidding halt in the early part of 1905 it was a pill worth swallowing for the sake of action, and a huge number successfully planned routes throughout major urban housing networks intent upon speaking their collective mind.

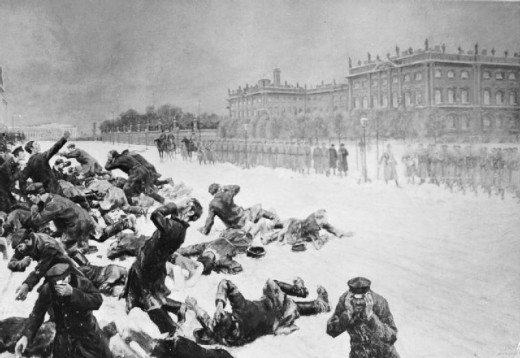

What followed would be nothing short of ruling class murder; even with the large contingent of rural voices chanting ‘God Save The Tsar’ and singing religious hymns, the protest was met by roadblocks constructed by Tsarist forces and a volley of bullets intent upon crushing dissent by any means necessary. The shooting of innocent, unarmed civilians in cold blood pierced the winter air, killing over 200 people and wounding over 800 amidst the terror and panic of the altercation. Workers, wives, children, priests and bystanders were subjected to the very real punishment that a ruling class will inflict upon those who dare to step out of line and refuse to bend towards the submission of capital.

The event cemented the dissatisfaction of an already incensed population beyond measure, with even many rural peasantry shaking off their conservative affiliations to push politically leftwards. Applications to join both the Bolshevik and Menshevik wings of the RSDLP began to accelerate beyond what could be feasibly catered for, with now Bolshevik front-runner Vladimir Lenin describing it as the radicalisation of a generation. Even as the Tsar hurried to proclaim a Consultative Duma (Parliament) in the aftermath, further strikes across industrial hubs and railway networks gained momentum as workers retaliated, looting firearms shops to protect themselves from any further onslaught of Tsarist forces.

Just like the events within Derry in 1972, ruling class murder upon a peaceful, conservative-minded demonstration had evidenced just how far the capitalist class will go to cement their hegemonic order over the wills and demands of ordinary people. We must remain firmly aware in contemporary times that the ruling class of all countries, including our own, remain unconcerned about the democratic wishes of ordinary people if it conflicts with their aims. Just as the Bolsheviks rose to power in subsequent years through collective energy and organisation, we too must unite as workers to demand a rewritten society that favours us rather than our oppressors. Workers of the world, unite.

David Swanson